2. 天津医科大学总医院急诊医学科 300052;

3. 大连市友谊医院重症医学科 116001

2. Department of Emergency Medicine, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin 300052, China;

3. Department of Critical Care Medicine, Dalian Friendship Hospital, Dalian 116100, China

脓毒症是重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)患者高病死率的主要原因[1-2]。贫血是ICU中脓毒症患者最常见的并发症之一[3]。已有研究证实脓毒症相关性贫血(即炎症性贫血)主要与炎症状态下机体铁代谢紊乱有关[4-9]。机体主要通过肝脏合成和分泌铁调素来调节铁代谢[10]。在脓毒症早期血铁调素浓度明显增加,血浆铁、转铁蛋白、转铁蛋白饱和度降低,铁蛋白浓度反应性升高,使骨髓造血细胞无法获得足够的原料,导致贫血[8-9, 11-12]。

铁的缺乏主要分为绝对性或功能性缺铁。当全身铁储存量低或耗尽时,就会出现绝对性缺铁;功能性缺铁时全身铁储存正常,但骨髓中的铁供应不足,功能性缺铁可存在于许多急性和慢性炎症状态中[13],且可与绝对性缺铁共存。铁是人类和病原微生物的必需营养素,细菌的生长需要铁,长期进化使它们可从铁含量很低的环境中获得铁,所以细菌感染时机体血浆铁降低也可能是限制细菌生长、抵抗感染的一个防御机制[14-16]。然而,目前关于ICU里脓毒症患者早期铁代谢变化的趋势、铁缺乏状况及其与患者预后的关系均研究较少;另外,关于脓毒症患者是否需要补铁也存在争议。本研究拟评估脓毒症存活或死亡患者铁代谢相关指标的动态变化,分析铁缺乏与预后的相关性,为临床上是否给脓毒症患者补铁治疗提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料收集2016年9月至2018年7月入住大连医科大学附属第一医院急诊ICU的脓毒症患者(n=130)。纳入标准:符合“脓毒症3.0”的诊断标准[17]。排除标准:⑴年龄 < 18岁;⑵因不同原因引起的慢性肝功能障碍或慢性肾脏病;⑶免疫性疾病或恶性肿瘤;⑷所有类型的贫血,入院前的创伤,或入院时和ICU住院期间明显失血(如胃肠道出血);⑸住院期间接受了血液制品的输注(以避免输注血液制品对血红蛋白和其他贫血相关参数的不良影响);⑹接受激素治疗;⑺住院期间放弃积极治疗。本研究方案经大连医科大学附属第一医院伦理委员会批准(批准号:YJ-KY-2018-01),并获患者或家属知情同意。根据国际脓毒症和感染性休克管理指南[18-19],所有入组患者在入住ICU后接受规范性治疗。另选取性别、年龄均匹配的健康志愿者为对照组(n=20)。

1.2 检测指标和方法记录所有纳入患者的性别、年龄、临床诊断、感染部位、所需的实验室检测结果等,计算入院时序贯器官衰竭评估(sequential organ failure assessment, SOFA)评分。入院后第1(健康志愿者为入组后)、3和7天,在含有肝素或乙二胺四乙酸的管中收集静脉血,离心(2 000 r/min)10 min后将血浆分装于-80 ℃冻存备检。

采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA法)检测血浆铁蛋白(Abcam,英国)、可溶性转铁蛋白受体(soluble transferrin receptor,sTFR,R & D,美国)、铁调素(优尔生公司,武汉)、白介素-6(interleukin-6,IL-6,优尔生公司,武汉)。计算sTFR(nmol/L)与log铁蛋白(ng/mL)的比值。通过自动血细胞分析仪(XN-2000,Sysmex,神户,日本)测量血红蛋白、平均红细胞体积(mean red blood cell volume, MCV)、平均红细胞血红蛋白(mean red blood cell hemoglobin, MCH)、平均红细胞血红蛋白浓度(mean red blood cell hemoglobin concentration, MCHC)和红细胞分布宽度(red blood cell distribution width, RDW);通过自动生化分析仪(7600 Series,HITACHI,东京,日本)测量转铁蛋白(transferrin, TRF)、总铁结合力(total iron binding capacity, TIBC)、未饱和铁结合力(unsaturated iron binding capacity, UIBC)和铁饱和度(saturation, SAT)。

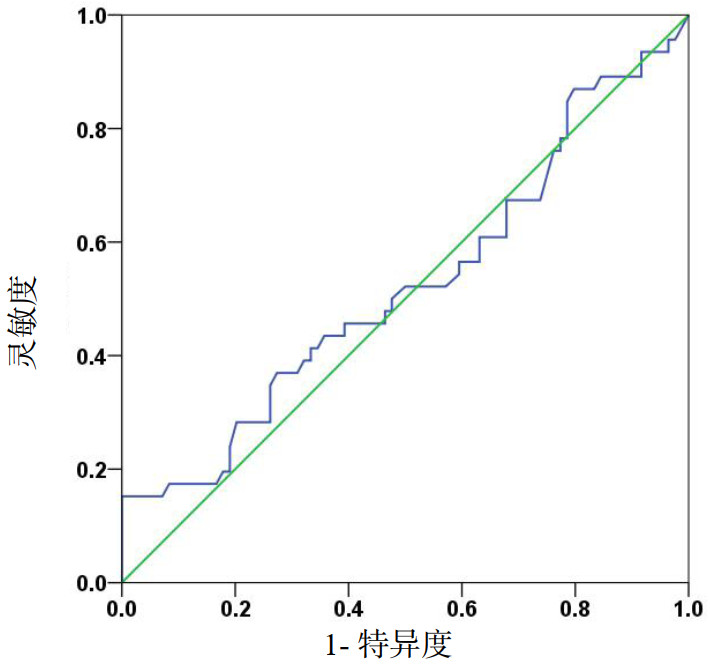

1.3 统计学方法应用SPSS 22.0统计软件进行统计分析。不符合正态分布的计量资料用中位数(四分位数)[M(QL, QU)]表示。性别、感染部位、入院时使用血管加压药的人数及机械通气人数的组间比较采用Fisher精确概率法;两两比较采用Bonferroni检验;非正态分布的计量资料组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis检验,两两比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;用Spearman等级相关检验评估变量之间的相关性;绘制血浆铁的受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic, ROC)曲线并计算曲线下面积(areas under the ROC curve, AUC)对28 d病死率进行预测。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 基线数据的比较存活组(n=84)和死亡组(n=46)在年龄、性别、脓毒症的来源及使用血管加压药的患者数之间的差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05,表 1)。与存活组相比,死亡组机械通气患者数、乳酸、肌酐和SOFA评分均增加,氧合指数、网织红细胞数、平均红细胞体积、平均红细胞血红蛋白和平均红细胞血红蛋白浓度均降低(均P < 0.05,表 1)。

| 指标 | 对照组(n=20) | 存活组(n=84) | 死亡组(n=46) | 统计值 | P值a |

| 年龄(岁) | 65.6(49, 78) | 67.5(36, 83) | 69.6(28, 85) | -1.040 | 0.782 |

| 男性(例,%) | 12(60.0) | 47(56.0) | 27(58.7) | - | 0.854 |

| 脓毒症的来源(例,%) | |||||

| 肺 | — | 53(63.1) | 27(58.7) | - | 0.707 |

| 腹腔 | — | 9(10.7) | 6(13.1) | - | 0.776 |

| 胆道 | — | 17(20.2) | 8(17.4) | - | 0.817 |

| 肾脏 | — | 3(3.6) | 3(6.5) | - | 0.665 |

| 皮肤/软组织 | — | 2(2.4) | 2(4.3) | - | 0.614 |

| 入院时使用升压药(例,%) | — | 5(6.0) | 3(6.5) | - | 0.898 |

| 机械通气(例,%) | — | 29(34.5) | 38(82.6) | - | < 0.05 |

| 氧合指数(mmHg) | 406(375, 433) | 243(187, 288) | 172(140, 204) | -5.590 | < 0.05 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L) | 1.0(0.7, 1.4) | 2.4(1.8, 2.8) | 4.1(2.9, 5.1) | -7.230 | < 0.05 |

| 肌酐(µmol/L) | 75(49, 87) | 107(81, 135) | 147(120, 165) | -5.403 | < 0.05 |

| 网织红细胞数(×109/L) | 87(79, 101) | 62(53, 78) | 45(34, 56) | -5.986 | < 0.05 |

| 平均红细胞体积(fL) | 90(86, 94) | 84(80, 90) | 79(74, 84) | -4.948 | < 0.05 |

| 平均红细胞血红蛋白量(pg) | 30(29, 31) | 29(26, 32) | 26(24, 29) | -4.562 | < 0.05 |

| 平均红细胞血红蛋白浓度(g/L) | 335(326, 344) | 327(314, 341) | 309(297, 314) | -6.907 | < 0.05 |

| SOFA | — | 7(5, 8) | 10(7, 11) | -4.810 | < 0.05 |

| 注:SOFA, 序贯器官衰竭评估。a存活组和死亡组之间的比较 | |||||

在入院第1周,脓毒症患者血红蛋白浓度随时间逐渐降低,第3天和第7天出现显著贫血(表 2);入院第1周的血浆铁、转铁蛋白、铁饱和度、总铁结合力及未饱和铁结合力均显著低于对照组;红细胞分布宽度、铁蛋白、IL-6、铁调素和可溶性转铁蛋白受体显著高于对照组(均P < 0.05)。第3、7天的红细胞分布宽度、铁蛋白和铁调素,以及第7天的血浆铁和铁饱和度均显著高于第1天,而第7天的总铁结合力和未饱和铁结合力,以及第3天的sTFR/log铁蛋白显著低于第1天(均P < 0.05)。

| 指标 | 对照组(n=23) | 脓毒症患者入ICU后(n=130) | ||

| 第1天 | 第3天 | 第7天 | ||

| 血红蛋白(g/L) | 135(132, 138) | 124(114, 136)a | 103(98, 110)ab | 95(90, 101)ab |

| 红细胞分布宽度(%) | 13.1(12.6, 13.3) | 13.5(12.6, 14.2) | 14.3(13.5, 151)ab | 14.6(13.8, 15.6)ab |

| 铁蛋白(ng/mL) | 30.3(29.5, 31.4) | 192.7(165.6, 214.8)a | 565.3(535.4, 581.6)ab | 297.1(222.3, 318.1)ab |

| 白介素-6(pg/mL) | 5.3(3.8, 6.6) | 39.9(28.8, 104.0)a | 28.1(21.9, 69.5)ab | 30.5(18.9, 45.5)ab |

| 铁(µmol/L) | 16.2(14.5, 20.4) | 7.5(5.4, 10.7)a | 7.2(5.6, 9.3)a | 8.6(5.3, 12.5)ab |

| 转铁蛋白(g/L) | 2.6(2.2, 2.9) | 1.4(1.1, 1.7)a | 1.3(1.1, 1.7)a | 1.3(0.8, 1.7)a |

| 铁饱和度(%) | 37(32, 42) | 21(16, 28)a | 23(16, 31)a | 28(21, 36)ab |

| 总铁结合力(µmol/L) | 46.6(42.1, 49.3) | 36.1(29.1, 42.4)a | 33.9(25.2, 42.7) a | 31.6(22.7, 41.6)ab |

| 未饱和铁结合力(µmol/L) | 28.2(26.2, 32.6) | 28.1(21.5, 34.9) | 23.9(17.6, 35.2)a | 21.0(15.2, 32.7)ab |

| 铁调素(ng/mL) | 21.2(20.0, 22.8) | 147.9(127.9, 163.0)a | 76.0(59.5, 96.1)ab | 48.2(40.6, 58.3)ab |

| sTFR(nmol/L) | 15.1(14.5, 15.5) | 24.2(20.5, 27.2)a | 24.3(21.3, 37.4)a | 25.5(21.8, 28.6)a |

| sTFR / log铁蛋白 | 10.2(9.5, 10.8) | 10.7(9.2, 12.1)a | 8.8(7.7, 10.0)ab | 10.4(8.9, 11.9) |

| 注:sTFR为可溶性转铁蛋白受体;与对照组比较,aP < 0.05;与入ICU后第1天比较,bP < 0.05 | ||||

入院第1周,存活和死亡组脓毒症患者的血红蛋白水平均随时间逐渐下降,在第3天和第7天均出现显著贫血,但死亡组贫血更严重(均P < 0.05,表 3)。入院第1周死亡组的转铁蛋白、总铁结合力和未饱和铁结合力,以及第3和7天死亡组的血浆铁均显著低于存活组(均P < 0.05);而入院第1周死亡组的铁蛋白、IL-6和铁调素,以及第7天铁饱和度均显著高于存活组(均P < 0.05)。两组患者第3和7天的红细胞分布宽度和铁蛋白,以及第7天死亡组的铁饱和度和sTFR均显著高于第1天,而两组患者第3和7天的血浆铁和铁调素,第3天的sTFR/log铁蛋白,以及第7天死亡组的转铁蛋白、总铁结合力和未饱和铁结合力均显著低于第1天(均P < 0.05)。

| 指标 | 入ICU后 | ||

| 第1天 | 第3天 | 第7天 | |

| 血红蛋白(g/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 125(116, 136) | 104(98, 111)b | 94(90, 106)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 123(112, 134) | 99(96, 110)ab | 82(72, 99)ab |

| 红细胞分布宽度(%) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 13.4(12.6, 14.2) | 14.2(13.4, 15.0)b | 14.1(13.5, 14.9)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 13.6(12.6, 14.3) | 14.6(13.8, 15.5)b | 15.6(14.7, 16.2) b |

| 铁蛋白(ng/mL) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 172.5(151.6, 193.9) | 555.0(522.6, 572.6) b | 276.7(190.0, 308.5)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 227.1(214.8, 241.7)a | 581.9(560.5, 594.1)ab | 324.9(311.2, 342.6)ab |

| 白介素-6 (pg/mL) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 33.7(23.9, 39.4) | 24.0(19.1, 27.9)b | 23.4(18.1, 38.1)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 122.2(98.0, 149.6)a | 75.4(65.2, 97.5)ab | 43.9(30.3, 56.1)ab |

| 铁(µmol/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 7.5(5.4, 10.7) | 8.6(5.9, 11.1)b | 10.8(6.5, 14.6)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 7.6(5.4, 11.2) | 6.5(5.6, 7.3)ab | 6.7(3.9, 8.9)ab |

| 转铁蛋白(g/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 1.6(1.2, 1.8) | 1.5(1.2, 1.9) | 1.6(1.1, 1.9) |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 1.2(0.8, 1.5)a | 1.1(0.6, 1.4)a | 0.8(0.6, 1.1)ab |

| 铁饱和度(%) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 20(15, 25) | 23(15, 30) | 27(20, 36)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 21(19, 43) | 24(16, 31) | 30(24, 36)ab |

| 总铁结合力(µmol/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 38.2(32.1, 43.7) | 36.7(29.1, 44.3) | 38.8(30.7, 44.6) |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 29.6(21.0, 39.0)a | 25.4(19.4, 38.6)a | 23.2(17.1, 28.9)ab |

| 未饱和铁结合力(µmol/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 30.0(24.6, 36.5) | 25.8(20.6, 36.9) | 27.7(18.0, 36.0) |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 21.8(13.0, 30.2)a | 18.2(13.2, 32.8)a | 16.4(11.5, 20.2) ab |

| 铁调素(ng/mL) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 137.4(113.9, 148.5) | 66.5(49.4, 76.9)b | 47.6(38.8, 51.8)b |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 171.5(157.1, 184.4)a | 98.8(95.1, 105.4)ab | 60.9(44.4, 69.7)ab |

| sTFR (nmol/L) | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 24.3(22.1, 26.5) | 24.1(21.0, 28.3) | 24.2(19.1, 28.4) |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 23.0(19.6, 28.0) | 24.3(21.3, 26.6) | 25.6(23.5, 28.8)b |

| sTFR/log铁蛋白 | |||

| 存活组(n=84) | 11.0(9.7, 12.1) | 8.9(7.7, 10.4)b | 10.9(9.5, 12.2) |

| 死亡组(n=46) | 9.7(8.3, 12.2) | 8.8(7.7, 9.6)b | 9.5(7.7, 11.2) |

| 注:sTFR为可溶性转铁蛋白受体;与存活组比较,aP < 0.05;与入ICU后第1天比较,bP < 0.05 | |||

Spearman相关性分析表明血浆铁与IL-6(r= -0.391,P < 0.01)、铁蛋白(r=-0.293,P=0.001)、铁调素(r=-0.209,P=0.017)均呈负相关(表 4),而与sTFR/log铁蛋白(r=0.115,P=0.193)、血红蛋白(r=0.005,P=0.958)不相关。

| 指标 | 血浆铁 | |

| r | P | |

| 血红蛋白 | 0.005 | 0.958 |

| 铁调素 | -0.209 | 0.017 |

| 铁蛋白 | -0.293 | 0.001 |

| 白介素-6 | -0.391 | < 0.01 |

| sTFR/log铁蛋白 | 0.115 | 0.193 |

血浆铁预测脓毒症患者28 d死亡的工作曲线下面积(AUC)为0.524(95%CI:0.416~0.631,P=0.656,图 1),提示血浆铁不能预测脓毒症患者28 d死亡。

|

| 图 1 血浆铁预测脓毒症患者28 d死亡的受试者工作特征曲线 Fig 1 Receiver operating characteristic curves of plasma iron for predicting 28-day mortality in sepsis patients |

|

|

本研究发现脓毒症患者入住ICU早期即出现血红蛋白进行性下降,并且血浆铁、转铁蛋白、sTFR/log铁蛋白显著降低,而血浆sTFR、铁调素、铁蛋白和IL-6显著升高,提示脓毒症患者早期存在贫血和显著的铁代谢紊乱[20-22]。然而,Spearman相关性分析发现血浆铁与白介素-6、铁蛋白、铁调素均呈负相关,但与血红蛋白不相关。这可能是由于脓毒症贫血的发生机制复杂,除了与血铁水平降低、营养缺乏、促红细胞生成素产生减少且反应低下、红细胞的寿命缩短、医源性失血等有关外,还主要与炎症诱导的铁调素异常有关[9]。

脓毒症铁代谢的紊乱和相关的贫血受炎症影响[5, 23]。病原体入侵机体后,内毒素诱导单核-巨噬细胞产生IL-6,通过IL-6/JAK2/STAT3信号通路上调铁调素在肝脏的合成[24]。铁调素是铁代谢的中心环节,通过下调肠黏膜细胞和巨噬细胞膜铁转运蛋白的表达,抑制肠道吸收铁并促进巨噬细胞内的铁储存,从而引起血浆铁下降[25-26]。所以,脓毒症患者虽然血浆铁水平降低,但细胞内(主要是巨噬细胞)的铁储存增加,尽管有足够的铁储存,却无法有效地使用铁进行红细胞生成,即存在功能性铁缺乏[27]。Muñoz等[28]研究表明炎症性贫血患者中铁缺乏症的患病率为21%。因而,在脓毒症患者中绝对性缺铁和功能性缺铁可能并存。

然而,血浆铁水平降低对机体的影响是有争议的。一方面,由于细菌生长需要铁,所以血浆铁降低可能是限制细菌生长和抵抗感染的一个防御机制[14, 29];另一方面,缺铁可能对感染患者有害,已有研究表明缺铁与血流感染风险增加有关,铁状态与感染易感性之间存在U形关系[30-31]。本研究发现死亡组脓毒症患者的血浆铁水平更低,认为与缺铁可能引起缺铁性贫血并从而恶化患者的病情有关。所以,本研究发现的血浆铁并不能预测脓毒症患者28 d病死率,可能与血浆铁水平降低对机体具有类似相反效应的上述因素有关。

目前脓毒症贫血患者补铁治疗的必要性和安全性存在争议,其主要原因可能是ICU中脓毒症患者铁代谢紊乱的状态和机制尚不完全清楚[32]。补充铁剂可改善脓毒症相关性贫血,尤其是当合并严重缺铁性贫血时。然而,铁有潜在毒性,盲目补铁可引起不良影响。首先,补铁本身有不良影响,比如快速静脉补铁时,释放的游离铁可引起急性铁中毒,甚至心脏骤停;铁作为羟自由基形成的催化剂,也能加重氧化应激。其次,由于血浆铁浓度降低本身是抑制细菌增殖的一种防御机制,所以补铁还可能削弱这种防御机制[8]。另外,考虑到炎症性贫血复杂的病理机制,补充铁剂不太可能进一步刺激红细胞生成[33]。有研究证明,补铁虽然增加血浆铁,但对转铁蛋白饱和度、血红蛋白、输血需求、感染率、住院时间和病死率均无显著影响[18]。接受补铁治疗的患者比不接受补铁治疗的患者更容易发生感染[34-35]。尤其是,补充过量的铁还会损害巨噬细胞和中性粒细胞的吞噬和趋化性质,并影响T淋巴细胞反应[36-37]。还有研究发现高血浆铁水平与脓毒症患者的病死率增加有关[38]。然而,随着抗感染治疗的进行和炎症的好转,降低的血浆铁水平也可能改善。本研究发现ICU中脓毒症患者在接受全面治疗后随着炎症因子的下降,血浆铁水平较前增加,尤其是存活组的脓毒症患者。笔者认为这可能是铁重新分配的结果。因而,相比直接补铁外,针对从巨噬细胞到血液循环的铁重新分配的策略(铁再分配策略)可能是将来一个很有希望的治疗策略[39]。

本研究有两个不足之处。未能除外医源性失血等因素对研究结果的影响。此外,本研究为单中心研究,样本量相对较少,可能需要扩大样本量证实研究结果。

综上所述,脓毒症患者早期存在显著的贫血和铁代谢紊乱,而死亡组患者贫血和铁代谢紊乱更严重;血浆铁水平降低不能预测脓毒症患者28 d病死率。另外,血浆铁水平降低与血红蛋白降低不相关,补铁的必要性和安全性仍需要进一步研究,所以脓毒症患者补铁要慎重。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] | Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts[J]. JAMA, 2014, 312(1): 90-92. DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.5804 |

| [2] | 季兵, 朱建良, 马丽梅, 等. 早期集束化治疗对脓毒症及脓毒性休克患者预后的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2019, 28(2): 170-174. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.02.008 |

| [3] | Hayden SJ, Albert TJ, Watkins TR, et al. Anemia in critical illness: insights into etiology, consequences, and management[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2012, 185(10): 1049-1057. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201110-1915CI |

| [4] | Tacke F, Nuraldeen R, Koch A, et al. Iron parameters determine the prognosis of critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care Med, 2016, 44(6): 1049-1058. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001607 |

| [5] | Vincent JL. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients[J]. JAMA, 2002, 288(12): 1499-1507. DOI:10.1001/jama.288.12.1499 |

| [6] | van Eijk LT, Kroot JJ, Tromp M, et al. Inflammation-induced hepcidin-25 is associated with the development of anemia in septic patients: an observational study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(1): R9. DOI:10.1186/cc9408 |

| [7] | Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation[J]. Blood, 2019, 133(1): 40-50. DOI:10.1182/blood-2018-06-856500 |

| [8] | 姜毅, 龚平. 铁代谢紊乱与脓毒症[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(2): 229-232. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.02.027 |

| [9] | 安萌萌, 龚平. 脓毒症相关性贫血发病机制及治疗的研究进展[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(10): 1175-1178. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.10.025 |

| [10] | Collins JF, Wessling-Resnick M, Knutson MD. Hepcidin regulation of iron transport[J]. J Nutr, 2008, 138(11): 2284-2288. DOI:10.3945/jn.108.096347 |

| [11] | Piagnerelli M, Cotton F, Herpain A, et al. Time course of iron metabolism in critically ill patients[J]. Acta Clin Belg, 2013, 68(1): 22-27. DOI:10.2143/ACB.68.1.2062715 |

| [12] | Weiss G. Anemia of chronic disorders: new diagnostic tools and new treatment strategies[J]. Semin Hematol, 2015, 52(4): 313-320. DOI:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.004 |

| [13] | Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, et al. Iron deficiency anaemia[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10021): 907-916. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60865-0 |

| [14] | Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2015, 15(8): 500-510. DOI:10.1038/nri3863 |

| [15] | Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3[J]. Blood, 2006, 108(9): 3204-3209. DOI:10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631 |

| [16] | Cartwright GE, Lauritsen MA, Humphreys S, et al. The anemia associated with chronic infection[J]. Science, 1946, 103(2664): 72-73. DOI:10.1126/science.103.2664.72 |

| [17] | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [18] | Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(3): 486-552. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255 |

| [19] | Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012[J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41(2): 580-637. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af |

| [20] | Ganz T. Systemic iron homeostasis[J]. Physiol Rev, 2013, 93(4): 1721-1741. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00008.2013 |

| [21] | Fleming RE, Sly WS. Hepcidin: a putative iron-regulatory hormone relevant to hereditary hemochromatosis and the anemia of chronic disease[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001, 98(15): 8160-8162. DOI:10.1073/pnas.161296298 |

| [22] | 姜毅, 安萌萌, 龚平. 乌司他丁对脓毒症患者铁代谢及病情严重程度和预后的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2019, 28(3): 361-365. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.03.016 |

| [23] | Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism[J]. N Engl J Med, 1999, 341(26): 1986-1995. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199912233412607 |

| [24] | Kemna E, Pickkers P, Nemeth E, et al. Time-course analysis of hepcidin, serum iron, and plasma cytokine levels in humans injected with LPS[J]. Blood, 2005, 106(5): 1864-1866. DOI:10.1182/blood-2005-03-1159 |

| [25] | Stefanova D, Raychev A, Arezes J, et al. Endogenous hepcidin and its agonist mediate resistance to selected infections by clearing non-transferrin-bound iron[J]. Blood, 2017, 130(3): 245-257. DOI:10.1182/blood-2017-03-772715 |

| [26] | Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis[J]. Science, 2012, 338(6108): 768-772. DOI:10.1126/science.1224577 |

| [27] | Darveau M, Denault AY, Blais N, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: iron metabolism in critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care, 2004, 8(5): 356-362. DOI:10.1186/cc2862 |

| [28] | Muñoz M, Romero A, Morales M, et al. Iron metabolism, inflammation and anemia in critically ill patients. A cross-sectional study[J]. Nutr Hosp, 2005, 20(2): 115-120. |

| [29] | Jurado RL. Iron, infections, and anemia of inflammation[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1997, 25(4): 888-895. DOI:10.1086/515549 |

| [30] | Mohus RM, Paulsen J, Gustad L, et al. Association of iron status with the risk of bloodstream infections: results from the prospective population-based HUNT Study in Norway[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(8): 1276-1283. DOI:10.1007/s00134-018-5320-8 |

| [31] | Swenson ER, Porcher R, Piagnerelli M. Iron deficiency and infection: another pathway to explore in critically ill patients?[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(12): 2260-2262. DOI:10.1007/s00134-018-5438-8 |

| [32] | Litton E, Lim J. Iron metabolism: an emerging therapeutic target in critical illness[J]. Crit Care, 2019, 23(1): 81. DOI:10.1186/s13054-019-2373-1 |

| [33] | Sears DA. Anemia of chronic disease[J]. Med Clin North Am, 1992, 76(3): 567-579. DOI:10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30340-6 |

| [34] | Barry DM, Reeve AW. Increased incidence of gram-negative neonatal sepsis with intramuscula iron administration[J]. Pediatrics, 1977, 60(6): 908-912. |

| [35] | Murray MJ, Murray AB, Murray MB, et al. The adverse effect of iron repletion on the course of certain infections[J]. Br Med J, 1978, 2(6145): 1113-1115. DOI:10.1136/bmj.2.6145.1113 |

| [36] | Marx JJ. Iron and infection: competition between host and microbes for a precious element[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol, 2002, 15(2): 411-426. DOI:10.1053/beha.2002.0001 |

| [37] | Weiss G. Iron and immunity: a double-edged sword[J]. Eur J Clin Invest, 2002, 32(Suppl 1): 70-78. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.0320s1070.x |

| [38] | Lan P, Pan KH, Wang SJ, et al. High serum iron level is associated with increased mortality in patients with sepsis[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 11072. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-29353-2 |

| [39] | Petzer V, Theurl I, Weiss G. Established and emerging concepts to treat imbalances of iron homeostasis in inflammatory diseases[J]. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2018, 11(4): E135. DOI:10.3390/ph11040135 |

2021, Vol. 30

2021, Vol. 30