2 北京医院 国家老年医学中心外科ICU 100730;

3 解放军总医院第四医学中心烧伤整形科 100048

2 Department of Surgical Intensive Care Unit, Beijing Hospital, National Center of Gerontology, Beijing 100730, China;

3 Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery, Fourth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100048, China

住院患者常见的软组织感染包括蜂窝织炎、脓肿、坏死性筋膜炎、感染性坏疽或压疮、切口或创面感染等[1],若治疗不及时发展为脓毒症甚至脓毒性休克时伴有较高的并发症发生率及病死率[2-3]。早期诊断脓毒症和脓毒性休克是降低其并发症和病死率的关键[4-5]。

2016年脓毒症国际共识会议将脓毒症重新定义为感染导致的致命的器官功能不全的临床综合征[6],其诊断标准为存在感染且序贯器官衰竭评分(Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SOFA)改变≥ 2分,会议还建议采用快速序贯器官衰竭评分(quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, qSOFA)来快速筛查脓毒症患者[7]。本回顾性研究拟评估qSOFA评分用于预测软组织感染致脓毒性休克的准确性,并通过分析不同原发病患者的病原学、治疗方案及预后,为治疗软组织感染致脓毒性休克患者提供参考。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料本研究内容符合医学伦理标准,已获得北京医院伦理委员会批准(审批号:2017BJYYEC-146-01),治疗及检测均获得患者或家属的知情同意。本研究回顾性收集了2012年1月至2018年12月北京医院普通外科和解放军总医院第四医学中心烧伤整形科收治的软组织感染患者共192例。入选标准:入院或住院期间诊断为软组织感染,包括蜂窝织炎或丹毒、软组织脓肿、感染性坏疽或压疮、坏死性筋膜炎、切口或创面感染;年龄大于18岁。排除标准:软组织感染同时合并其他部位感染;临床资料不全;住院时间小于24 h。

1.2 研究方法回顾性收集患者一般资料:性别、年龄、原发病、基础疾病。记录患者血培养和伤口分泌物培养病原学、外科治疗方案及手术次数、支持治疗方案、住院期间是否出现随机血糖 > 10 mmol/L、是否入住ICU、28 d病死率。

脓毒症定义:存在感染且SOFA评分较基线值升高≥ 2分。根据患者既往病史做出基线评分;若患者缺少既往数据,则以入院时评分为基线数据。脓毒性休克定义:存在脓毒症,在充分容量复苏后仍需要升压药物维持平均动脉压≥ 65 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)且血乳酸 > 2 mmol /L。若病例资料缺少血乳酸数据,则依据临床诊断。qSOFA评分:呼吸频率≥ 22次/min,收缩压≤ 100 mmHg,意识改变,以上每项赋值1分,总分3分。

评估患者感染情况,采集患者入院时或病历记录感染首日的生命体征:收缩压、舒张压、平均动脉压、心率、呼吸频率、体温、格拉斯哥昏迷评分。采集诊断感染48 h内的实验室检查:白细胞、血小板、总胆红素、血尿素氮、血肌酐。记录动脉血气分析氧分压,无血气分析患者根据氧解离曲线公式进行估计[8-9]。

根据患者住院期间是否发生脓毒性休克分为脓毒性休克组和非脓毒性休克组,比较两组患者的基线数据、非手术治疗方案及预后。根据患者软组织感染病因分为坏死性筋膜炎、蜂窝织炎和脓肿、感染性压疮和坏疽、切口和创面感染四组,比较各组患者致病菌、外科治疗方案和脓毒性休克发病率。

1.3 统计学方法使用SPSS 20.0进行统计分析,正态分布数据以均数±标准差(Mean±SD)表示,两组间比较采用LSD- t检验。非正态分布数据采用中位数(四分位数)[M (QL, QU)]表示,多个独立样本间比较采用Kruskal Wallis检验。率的比较采用Fisher精确检验。计算qSOFA评分诊断脓毒症和脓毒性休克的敏感度、特异度、阳性预测值、阴性预测值,计算受试者工作特征曲线下面积(the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, AUC)。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

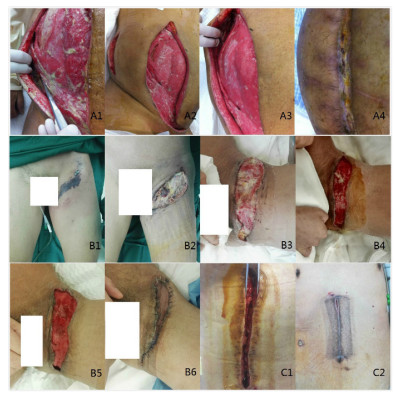

2 结果 2.1 患者基线资料和预后本研究共264例患者进入调查,排除72例,共纳入192例患者,诊断感染24 h内qSOFA ≥ 2分患者共47例(24.5%),诊断感染48 h内发生脓毒症患者79例(41.1%),住院期间发生脓毒性休克患者28例(14.6%), 死亡6例(3.1%)。共136(70.8%)例患者接受了手术治疗,采用真空封闭引流的患者47(24.5%)例。图 1示3例不同原发病因的软组织感染患者采用不同治疗方案的效果。

|

| A:例1钝性挫伤后腹壁坏死性筋膜炎;A1-A2:清创手术前后;A3-4:伤口换药后二期愈合;B:例2会阴坏死性筋膜炎(福尼尔坏疽);B1-5:术前及4次清创手术治疗后;B6:游离皮瓣移植术后;C1-2:例3腹壁切口感染真空封闭引流治疗前后 图 1 软组织感染的外科治疗效果 Fig 1 Surgical treatment effects of soft tissue infections |

|

|

脓毒性休克组患者和非休克组的年龄、性别、基础疾病比较差异均无统计学意义(均P > 0.05)。休克组患者在诊断感染24 h qSOFA ≥ 2分的比例(60.7% vs 18.3%,P= 0.001)和诊断感染48 h脓毒症发病率(82.1% vs 32.9%,P < 0.01)高于非脓毒性休克组。坏死性筋膜炎患者在脓毒性休克组比例显著高于非休克组(28.6% vs 8.5%, P= 0.002), 而蜂窝织炎和脓肿患者在脓毒性休克组比例显著低于非休克组(17.9% vs 40.9%, P= 0.02)。脓毒性休克组患者在住院期间随机血糖高于10 mmol/L的患者比例高于非休克组(67.9% vs 35.9%,P < 0.01)。脓毒性休克组患者的病死率(17.8% vs 0.6%,P < 0.01)和入住ICU人数比例(50% vs 10.3%,P < 0.01)均高于非休克组。休克组患者接受机械通气(32.1% vs 5.5%,P < 0.01)和肾脏替代治疗(10.7% vs 1.8%,P= 0.013)的患者比例也高于非休克组。两组患者基线数据、支持治疗和预后见表 1。

| 指标 | 合计 (n= 192) |

脓毒性休克 (n= 28) |

无脓毒性休克 (n= 164) |

统计值a | P值 | ||

| 年龄(岁, Mean±SD) | 58.8±18.0 | 62.0±17.4 | 58.2±18.1 | -1.023 | 0.308 | ||

| 男性(例,%) | 109(56.7) | 16(57.1) | 93(56.7) | 0.002 | 1.000 | ||

| 原发病(例,%) | |||||||

| 坏死性筋膜炎 | 22(11.4) | 8(28.6) | 14(8.5) | - | 0.006 | ||

| 蜂窝织炎和脓肿 | 72(37.5) | 5(17.9) | 67(40.9) | - | 0.021 | ||

| 感染性压疮和坏疽 | 73(38.0) | 11(39.3) | 62(37.8) | - | 1.000 | ||

| 切口和创面感染 | 25(13.0) | 4(14.3) | 21(12.8) | - | 0.766 | ||

| 基础疾病(例,%) | |||||||

| 高血压病 | 45(23.4) | 7(0.25) | 38(23.1) | - | 0.812 | ||

| 糖尿病 | 53(27.6) | 11(39.2) | 42(25.6) | - | 0.169 | ||

| 慢性肾病 | 5(2.6) | 3(10.7) | 2(1.2) | - | 0.023 | ||

| 心血管疾病 | 17(8.8) | 3(10.7) | 14(8.5) | - | 0.719 | ||

| 肿瘤 | 14(7.2) | 3(10.7) | 11(6.7) | - | 0.435 | ||

| 肝病或肝硬化 | 2(1.0) | 1(3.5) | 1(0.6) | - | 0.271 | ||

| 诊断感染24 h内qSOFA ≥ 2(例,%) | 47(24.5) | 17(60.7) | 30(18.3) | 23.282 | 0.001 | ||

| 诊断感染48 h内ΔSOFA ≥ 2(例,%) | 79(41.1) | 23(82.1) | 54(32.9) | 24.117 | < 0.01 | ||

| 住院期间随机血糖 > 10 mmol/L(例,%) | 78(40.6) | 19(67.9) | 59(35.9) | 10.078 | 0.003 | ||

| 28 d病死率(例,%) | 6(3.1) | 5(17.8) | 1(0.6) | - | < 0.01 | ||

| 住ICU患者(例,%) | 31(16.1) | 14(50.0) | 17(10.3) | 27.749 | < 0.01 | ||

| 机械通气(例,%) | 18(4.2) | 9(32.1) | 9(5.5) | - | < 0.01 | ||

| 肾脏替代治疗(例,%) | 6(3.1) | 3(10.7) | 3(1.8) | - | 0.041 | ||

| 注:a小样本组间的率的比较采用Fisher精确检验 | |||||||

根据病因分组发现,坏死性筋膜炎患者发生脓毒性休克比例(36.4 %)和28 d病死率(13.6%)均显著高于其他患者(均P < 0.05)。手术人次及手术次数差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05),但有更高比例(22.7%)的坏死性筋膜炎患者接受了皮瓣移植手术(表 2)。192例患者中最常见的病原学依次为甲氧西林敏感葡萄球菌(6.8%)、耐甲氧西林葡萄球菌(6.2%)、肠杆菌(5.7%)、肠球菌(5.2%)(表 3)。

| 指标 | 合计 (n= 192) |

坏死性筋膜炎 (n= 22) |

蜂窝织炎和脓肿 (n= 72) |

感染性压疮和坏疽 (n= 73) |

切口和创面感染 (n= 25) |

H值a | P值 |

| 住院期间发生脓毒性休克 | 28(14.6) | 8(36.4) | 5(6.9) | 11(15.1) | 4(16) | - | 0.010 |

| 28 d病死率 | 6(3.1) | 3(13.6) | 0 | 1(1.4) | 2(8) | - | 0.004 |

| 手术患者 | 136(70.8) | 19(86.4) | 48(66.7) | 52(71.2) | 17(68) | 3.276 | 0.343 |

| 手术次数[M(QL, QU)] | 1(0,1) | 1(1,2) | 1(0,1) | 1(0,1) | 1(0,1) | 5.307 | 0.151 |

| 皮瓣移植患者 | 10(5.2) | 5(22.7) | 0 | 3(4.1) | 2(8) | - | 0.001 |

| 真空封闭引流治疗 | 47(24.5) | 6(27.2) | 12(16.7) | 19(26) | 10(40) | - | 0.118 |

| 注:a小样本组间的率的比较采用Fisher精确检验 | |||||||

| 致病菌 | 坏死性筋膜炎 (n= 22) |

蜂窝织炎和脓肿 (n= 72) |

感染性压疮和坏疽 (n= 73) |

切口和创面感染 (n= 25) |

合计 (n = 192) |

| 分泌物或血培养阳性患者 | 17(77.2) | 22(30.5) | 30(41.1) | 13(52) | 82(69.1) |

| 耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌 | 3(13.6) | 1(1.4) | 6(8.2) | 2(8) | 12(6.2) |

| 甲氧西林敏感金黄色葡萄球菌 | 5(22.7) | 4(5.5) | 3(4.1) | 1(4) | 13(6.8) |

| 凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌 | 0 | 3(4.1) | 3(4.1) | 1(4) | 7(3.6) |

| 链球菌 | 0 | 2(2.7) | 4(5.5) | 2(8) | 8(4.2) |

| 肠球菌 | 4(18.1) | 2(2.7) | 3(4.1) | 1(4) | 10(5.2) |

| 肠杆菌 | 3(13.6) | 1(1.4) | 4(5.5) | 3(12) | 11(5.7) |

| 肺炎克雷伯 | 2(9.1) | 1(1.4) | 3(4.1) | 1(4) | 7(3.6) |

| 不动杆菌 | 1(4.5) | 3(4.1) | 1(1.4) | 1(4) | 6(3.1) |

| 奇异变形杆菌 | 0 | 0 | 1(1.4) | 0 | 1(0.5) |

| 脆弱拟杆菌 | 0 | 0 | 1(1.4) | 1(4) | 2(1) |

| 铜绿假单胞菌 | 2(9.1) | 1(1.4) | 1(1.4) | 1(4) | 5(2.6) |

| 其他病原菌 | 0 | 3(4.1) | 1(1.4) | 0 | 4(2.1) |

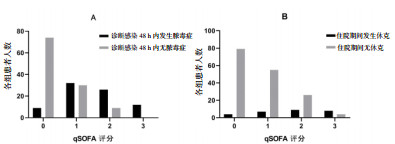

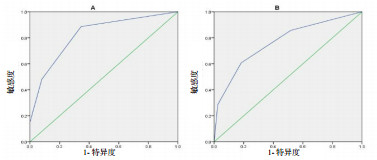

以qSOFA ≥ 2分为截断值,诊断脓毒症的敏感度为48.1%,特异度为92%,阳性预测值为80.8%,阴性预测值为71.7%,AUC为0.824(95% CI: 0.764~0.884,P < 0.01)。以qSOFA ≥ 2分为截断值,预测脓毒性休克的敏感度为60.7%,特异度为81.7%,阳性预测值为36.2%,阴性预测值为92.4%,AUC为0.767(95% CI: 0.665~0.869,P < 0.01)。脓毒症患者和脓毒性休克患者qSOFA评分见图 2,受试者工作特征曲线见图 3。

|

| A:诊断感染48 h内发生脓毒症患者的qSOFA评分;B:住院期间发生脓毒性休克患者的qSOFA评分 图 2 脓毒症和脓毒性休克患者的qSOFA评分 Fig 2 qSOFA score of patients with sepsis and septic shock |

|

|

|

| A:qSOFA诊断脓毒症的受试者工作特征曲线;B:qSOFA诊断脓毒性休克的受试者工作特征曲线 图 3 qSOFA诊断脓毒症和脓毒症休克的受试者工作特征曲线 Fig 3 The receiver operating characteristic curve of qSOFA score for diagnosis of sepsis and septic shock |

|

|

2016年美国重症医学会与欧洲重症医学会联合发布脓毒症3.0定义及诊断标准,同时还建议采用qSOFA来快速筛查脓毒症[6-7]。使用qSOFA评分早期筛查脓毒症已成为近年研究热点,国内外多项研究验证了其早期诊断脓毒症的准确性,也将其用于预测并发症和病死率[10-12]。软组织感染是外科常见疾病,住院患者中的发病率可达10% [1, 13]。起病时感染病灶通常较局限,但是治疗不及时可以引起脓毒症, 当迅速进展为脓毒性休克时病死率可高达17%~33% [14-16]。本研究中合并脓毒性休克的患者其病死率也达到17.8%,远高于非脓毒性休克组。而早期诊断脓毒症,治疗脓毒症休克是降低病死率的关键[4],因此对脓毒症和脓毒性休克的早期筛查至关重要。

由于SOFA评分依赖于完善的实验室检查,而普通病房的患者入院24 h内通常还没有完善的实验室检查结果,所以本研究计算了诊断感染48 h内的ΔSOFA,以此来区分患者是否存在脓毒症。结果发现,当以qSOFA ≥ 2为截断值时,用来预测软组织感染合并脓毒症,特异度较高(92%),而敏感度偏低(48.1%),这和既往研究结果相符[10, 17]。当以qSOFA ≥ 2分作为筛查工具,用来预测软组织感染合并脓毒性休克时,具有较好的特异度(81.7%),敏感度为60.7%,其阴性预测值较好(92.4%),而阳性预测值只有36.2%。由于qSOFA评分可以简单迅速完成,因此笔者建议可以先由普通病房完成qSOFA评分筛查。对于qSOFA ≥ 2的患者,需要进一步完善检查,评估患者有无全身感染和器官功能障碍,对于休克患者早期纠正休克。

软组织感染的危险因素包括高龄、糖尿病、肥胖、高血压、肝硬化、慢性肾病、自身免疫疾病等[18-20],坏死性筋膜炎患者中糖尿病的发生率可达到40% [15]。本研究中192例软组织感染患者中糖尿病发病率为27.6%,在脓毒性休克组和非脓毒性休克组患者间差异无统计学意义,但是休克组患者血糖控制情况较差,住院期间随机血糖 > 10 mmol/L的患者比例显著高于非休克组。另外,脓毒性休克患者中合并慢性肾病的比例显著高于非脓毒性休克组。总之,伴随老龄化程度发展,越来越多的住院患者会合并多种基础疾病,对于这一类患者出现软组织感染时,需要更加警惕发生脓毒性休克的风险。

本研究共有82例(69.1%)患者病原学培养阳性,最常见的细菌为甲氧西林敏感葡萄球菌、耐甲氧西林葡萄球菌、肠杆菌以及肠球菌,该结果和之前的研究结果相似[13, 21-22]。ICU当中的坏死性软组织感染常存在混合性感染[3],应联合有效的广谱抗生素进行治疗。对于严重的软组织感染,耐甲氧西林葡萄球菌是最常见的致病菌[23],因此患者合并脓毒性休克时的抗感染方案应该经验性覆盖耐甲氧西林葡萄球菌。对于高病死率的坏死性筋膜炎,指南推荐万古霉素联合哌拉西林/他唑巴坦作为一线治疗方案[1]。

本研究中,坏死性筋膜炎患者发生脓毒性休克的比例高于其他病因导致的软组织感染,住院病死率为13.6%。这和病变严重程度相关,坏死性筋膜炎可以从皮下组织、浅筋膜累及深筋膜及肌肉,文献报道其病死率最高有30%以上[3, 16]。CT检查有助于明确病变范围, 手指试验阳性可以用于临床诊断,即探查创面时可以使用手指将疏松的筋膜和肌肉组织进行钝性分离[24]。

外科治疗对于控制感染病灶非常重要。对于合并脓毒性休克的患者,需要在积极纠正休克的同时,创造手术机会。手术治疗的首要目的应该以尽早彻底清创、祛除感染病灶为主[25],深部的软组织感染部位可以放置引流管,使用稀释的碘伏或过氧化氢溶液持续冲洗。本研究共有10例患者接受了皮瓣移植手术,其中5例为坏死性筋膜炎,这类患者创面深,受累面积大,需要多次清创手术后再行皮瓣移植[26]。真空封闭引流可以封闭创面形成负压,在阻隔外部病原侵袭的同时,负压可以消除死腔和积液,降低组织间隙压力[27-28]。

本研究的局限性:⑴虽然采集了两个中心的数据,其样本量仍较小;⑵回顾性研究决定了其数据资料不够完善,对于缺少乳酸数据的少部分患者,根据临床情况做出了诊断;⑶在评估SOFA评分时对一部分患者的血氧分压根据氧解离曲线做了估计。

综上所述,qSOFA ≥ 2分可以作为预测成人软组织感染致脓毒性休克的快速筛查工具。早期诊断脓毒症,手术彻底清创及有效的抗感染治疗是救治该类患者成功的关键。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] | Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(2): e10-e52. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu444 |

| [2] | Hakkarainen TW, Kopari NM, Pham TN, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes[J]. Curr Probl Surg, 2014, 51(8): 344-362. DOI:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001 |

| [3] | Phan HH, Cocanour CS. Necrotizing soft tissue infections in the intensive care unit[J]. Crit Care Med, 2010, 38(9 Suppl): S460-S468. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ec667f |

| [4] | Westphal GA, Koenig A, Caldeira Filho M, et al. Reduced mortality after the implementation of a protocol for the early detection of severe sepsis[J]. J Crit Care, 2011, 26(1): 76-81. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.08.001 |

| [5] | Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008[J]. Crit Care Med, 2008, 36(1): 296-327. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000298158.12101.41 |

| [6] | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [7] | Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: For the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 762-774. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0288 |

| [8] | Ellis RK. Determination of PO2 from saturation[J]. J Appl Physiol, 1989, 67(2): 902. DOI:10.1152/jappl.1989.67.2.902 |

| [9] | Severinghaus JW. Simple, accurate equations for human blood O2 dissociation computations[J]. J Appl Physiol, 1979, 46(3): 599-602. DOI:10.1152/jappl.1979.46.3.599 |

| [10] | Finkelsztein EJ, Jones DS, Ma KC, et al. Comparison of qSOFA and SIRS for predicting adverse outcomes of patients with suspicion of sepsis outside the intensive care unit[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 73. DOI:10.1186/s13054-017-1658-5 |

| [11] | 张肖难, 张泓. SOFA、qSOFA评分及SIRS标准对急诊疑似感染患者预测价值研究[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(3): 259-264. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.03.007 |

| [12] | 濮雪华, 缪小莉, 揭红英, 等. qSOFA联合氧合指数对人感染H7N9禽流感的预后评估[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(7): 802-804. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.07.019 |

| [13] | Ki V, Rotstein C. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: A review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care[J]. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol, 2008, 19(2): 173-184. DOI:10.1155/2008/846453 |

| [14] | Napolitano LM. Severe soft tissue infections[J]. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2009, 23(3): 571-591. DOI:10.1016/j.idc.2009.04.006 |

| [15] | Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Papadopoulos I, et al. Early diagnosis and surgical treatment for necrotizing fasciitis: a multicenter study[J]. Front Surg, 2017, 4: 5. DOI:10.3389/fsurg.2017.00005 |

| [16] | Heitmann C, Pelzer M, Bickert B, et al. Surgical concepts and results in necrotizing fasciitis[J]. Chirurg, 2001, 72(2): 168-173. DOI:10.1007/s001040051287 |

| [17] | Rodriguez RM, Greenwood JC, Nuckton TJ, et al. Comparison of qSOFA with current emergency department tools for screening of patients with sepsis for critical illness[J]. Emerg Med J, 2018, 35(6): 350-356. DOI:10.1136/emermed-2017-207383 |

| [18] | Stenstrom R, Grafstein E, Romney M, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection in a Canadian emergency department[J]. CJEM, 2009, 11(5): 430-438. DOI:10.1017/s1481803500011623 |

| [19] | Huang KF, Hung MH, Lin YS, et al. Independent predictors of mortality for necrotizing fasciitis: a retrospective analysis in a single institution[J]. J Trauma, 2011, 71(2): 467-473. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e318220d7fa |

| [20] | Arif N, Yousfi S, Vinnard C. Deaths from necrotizing fasciitis in the United States, 2003-2013[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2016, 144(6): 1338-1344. DOI:10.1017/s0950268815002745 |

| [21] | Schulin T. Bacterial etiology of soft tissue infections[J]. Infection, 2018, 46(4): 577. DOI:10.1007/s15010-018-1145-1 |

| [22] | Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, et al. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998-2004)[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2007, 57(1): 7-13. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.05.009 |

| [23] | Dryden M. Complicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation[J]. Surg Infect, 2008, 9(Suppl 1): s3-s10. DOI:10.1089/sur.2008.066.supp |

| [24] | Agarwal L, Yasin A. Necrotising fasciitis: a fatal case of sepsis and a diagnostic challenge - case report and review of literature[J]. Int J Emerg Med, 2018, 11(1): 23. DOI:10.1186/s12245-018-0183-x |

| [25] | Boyer A, Vargas F, Coste F, et al. Influence of surgical treatment timing on mortality from necrotizing soft tissue infections requiring intensive care management[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2009, 35(5): 847-853. DOI:10.1007/s00134-008-1373-4 |

| [26] | Lin CT, Chang SC, Chen SG, et al. Reconstruction of perineoscrotal defects in Fournier's gangrene with pedicle anterolateral thigh perforator flap[J]. ANZ J Surg, 2016, 86(12): 1052-1055. DOI:10.1111/ans.12782 |

| [27] | Chen X, Liu L, Nie W, et al. Vacuum sealing drainage therapy for refractory infectious wound on 16 renal transplant recipients[J]. Transplant Proc, 2018, 50(8): 2479-2484. DOI:10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.04.014 |

| [28] | Vaienti L, Gazzola R, Benanti E, et al. Failure by congestion of pedicled and free flaps for reconstruction of lower limbs after trauma: the role of negative-pressure wound therapy[J]. J Orthop Traumatol, 2013, 14(3): 213-217. DOI:10.1007/s10195-013-0236-0 |

2020, Vol. 29

2020, Vol. 29