随着心肺复苏(cardiopulmonary resuscitation, CPR)技术普及和急救体系完善,心搏骤停(cardiac arrest,CA)患者自主循环恢复(restoration of spontaneous circulation, ROSC)率逐渐提高至47%,但出院存活率及生存质量未见改善[1-5]。ROSC后机体将出现一系列病理生理变化,即心脏骤停后综合征(post-cardiac arrest syndrome, PCAS),甚至生命终结[6]。因此CPR研究重点从提高ROSC率转向如何改善远期存活率和生存质量,即PCAS[7],目前公认有效方法只有早期亚低温治疗(mild therapeutic hypothermia, MTH)及恢复期的高压氧治疗。影响PCAS器官功能恢复主要为缺血-再灌注(I/R)损伤,氧化还原失衡为其主要机制之一。研究发现,硫氧还蛋白(rhioredoxin, Trx)在氧化应激中扮演重要角色[8],但相关研究较少。本实验主要观察不同时相行MTH对心搏骤停兔脑功能的影响。

1 材料与方法 1.1 实验动物及分组健康雄性日本大耳白兔45只,体质量2.5±0.5 kg,由中国农业科学院兰州兽医研究所提供[合格证号:SYXK(甘)2010-0001]。按随机数字表将动物分为6组:常温假手术组(NS,n=7)、亚低温假手术组(HS,n=7)、常温复苏组(NR,n=8)、CA前亚低温组(HP,n=7)、复苏后30 min亚低温组(HRe30,n=7)和复苏后90 min亚低温组(HRe90,n=9)。NS和HS组不建立CPR模型,HP、HRe30、HRe90组分别在CA前、ROSC后30 min和90 min采用体表降温法诱导亚低温并维持至实验结束,NR组建模后维持生理体温。

1.2 动物模型制备及处理经兔耳缘静脉缓慢注射20%乌拉坦4 mL/kg麻醉。行气管插管,左心导管和右股动脉置管,利用BL-420生物系统连续监测ECG和血流动力学指标。维持MAP>80 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa),保证脑灌注压。肛温表探头伸入肛内5 cm,维持2 min后读数,动态记录肛温。

在心尖搏动点和右锁骨下放置电极,50 V直流电持续放电60~100 s诱发室颤并维持3 min后开始复苏(按Utstein-CPR动物复苏标准指南)[9],即徒手胸外按压、呼吸机辅助通气(HX-200动物呼吸机),耳缘静脉注射肾上腺素15 μg/kg等。复苏2 min为一循环,循环末若ECG为室颤波或正常动脉搏动波消失,使用除颤仪(TEC-7621C)予30 J双相波除颤,随后继续胸外按压。若ECG示自主心律,MAP≥60 mmHg并持续10 min则判定复苏成功。复苏后600 min过量麻醉处死动物并迅速开颅,常规解剖了解手术或复苏过程有无机械性损伤,留取全脑组织标本,待海马CA1区病理学检查并统计凋亡指数(AI)。

1.3 体温控制采用体表降温法(在腋窝、腹股沟等处放置生物冰袋)诱导亚低温(33~35 ℃)[10]维持至实验终点,同时缓慢泵入瑞芬太尼6.0 μg/(kg·min)减轻寒战等不良反应。常温组用电热毯维持生理体温(39.0±0.5)℃。

1.4 检测指标及方法 1.4.1 血流动力学指标和血清NSE、Trx浓度测定分别在CA前15 min,ROSC后30、60、120、360和600 min记录血流动力学指标,并采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)待测血清NSE、Trx浓度。

1.4.2 病理学观察采用原位末端缺刻标记(TUNEL)法染色,光镜(Olymps)观察每400倍视野下海马CA1区神经元细胞凋亡形态并统计凋亡指数(AI)。

1.5 统计学方法采用SPSS 19.0处理数据,计量资料呈正态分布以均数±标准差(x±s)表示。时间变化资料比较用重复测量方差分析,组间比较用单因素方差分析,率比较用χ2检验,计数资料比较用Fisher精确概率法,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 模型制备及复苏情况制备模型诱发CA时间为60~100 s,(75.04±12.3)s,ROSC时间为169~223 s,(195.17±19.4)s,共28只复苏成功(90.3 %),NR组有2只、HRe90组有1只复苏失败。

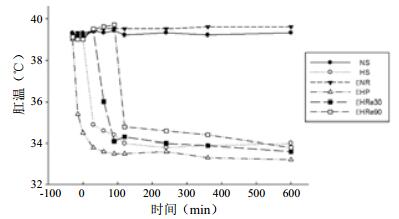

2.2 温度变化情况各组动物在观察期间肛温均在目标范围。亚低温诱导28~38 min达目标肛温,并维持至实验终点,符合设计方案(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 各组肛温变化 Figure 1 Changes of the rectal temperature of each group |

|

|

CA前各组血流动力学比较差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05),亚低温各组HR低于常温组(均P < 0.05);HP组LVEDP于复苏后30 min低于NR、HRe30和HRe90组(均P < 0.05);NR组LVEDP复苏后持续上升,并高于其他复苏组;HP组+dp/dtmax于复苏后30 min、120 min高于NR和HRe90组(均P < 0.05);HP组-dp/dtmax于复苏后各时间点高于NR组(均P < 0.05);复苏组MAP各时间点差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05),见表 1。

| 指标 | CA前15 min | ROSC后 | ||||

| 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 360 min | 600 min | ||

| HR(次/min) | ||||||

| NR组 | 291.0±11.2 | 300.0±17.5 | 284.0±22.4 | 297.0±18.2 | 287.5±12.5 | 295.5±10.6 |

| HP组 | 251.0±3.1a | 241.5±4.6a | 227.0±11.8a | 207.5±5.9a | 195.8±3.5a | 200.6±7.1a |

| HRe30组 | 269.5±6.5 | 239.4±13.6a | 222.0±15.3a | 219.0±13.4a | 189.3±2.9a | 171.3±7.3a |

| HRe90组 | 260.5±15.3 | 239.3±11.7a | 250.5±12.6a | 237.1±10.1a | 227.7±3.2a | 228.5±9.3a |

| NS组 | 257.0±14.0 | 266.0±15.5 | 263.0±17.0 | 281.0±13.5 | 272.0±15.0 | 281.0±14.1 |

| HS组 | 244.5±4.9a | 246.3±1.4a | 238.7±2.5a | 232.1±19.8a | 228.4±15.9a | 239.7±14.7a |

| MAP(mmHg) | ||||||

| NR组 | 84.1±1.7 | 83.1±2.0 | 78.7±1.9 | 77.0±2.8 | 78.2±2.1 | 74.9±2.0 |

| HP组 | 79.2±1.0 | 80.3±1.1 | 77.63±2.6 | 78.0±3.7 | 76.5±5.1 | 75.1±1.3 |

| HRe30组 | 92.2±3.0 | 87.1±1.8 | 80.3±2.2 | 78.4±4.5 | 76.3±1.9 | 75.0±3.9 |

| HRe90组 | 93.6±2.7 | 88.9±2.1 | 81.3±1.5 | 76.0±2.2 | 76.8±1.9 | 76.1±1.2 |

| NS组 | 86.3±1.3 | 84.2±1.2 | 89.2±4.2 | 91.4±0.6 | 92.2±2.8 | 99.1±0.9 |

| HS组 | 89.3±5.0 | 83.7±2.5 | 79.4±2.0 | 73.6±1.1 | 82.5±4.4 | 72.1±3.1 |

| LVEDP(mmHg) | ||||||

| NR组 | 2.4±0.9 | 4.6±1.0 | 8.0±1.1 | 11.4±0.9 | 13.9±1.0 | 14.9±0.7 |

| HP组 | 2.8±0.7 | 3.4±0.8cdf | 5.1±0.4 | 6.0±0.9 | 6.5±0.4 | 7.2±1.0 |

| HRe30组 | 2.3±0.7 | 4.1±0.5 | 6.5±0.3 | 8.4±0.9 | 10.1±0.6 | 10.7±0.9 |

| HRe90组 | 1.7±0.6 | 4.3±0.2 | 6.7±0.3 | 10.5±1.2 | 11.3±0.5 | 11.6±0.6 |

| NS组 | 3.1±0.3 | 2.8±0.4 | 2.9±0.2 | 3.2±0.4 | 2.7±0.3 | 2.5±0.2 |

| HS组 | 2.1±0.5 | 3.2±0.8 | 2.9±0.4 | 3.1±0.7 | 3.3±0.4 | 3.4±0.2 |

| Peak+dP/dtmax(mmHg/s) | ||||||

| NR组 | 12 145.6±301.9 | 9 079.8±298.0 | 8 770.7±359.4d | 7 375.9±326.8d | 6 803.9±270.6 | 6 399.1±478.1 |

| HP组 | 11 560.4±311.5 | 10 970.2±148.1cf | 10 264.7±165.2 | 10 391.7±538.2cf | 11 047.3±556.8 | 11 251.4±263.2 |

| HRe30组 | 11 957.4±310.7 | 11 080.9±203.5 | 9 988.4±195.2 | 9 688.7±200.3 | 9 719.7±180.3 | 9 900.3±110.5 |

| HRe90组 | 12 348.7±256.7 | 11 581.4±203.5 | 9 108.8±197.8d | 8 759.8±279.6d | 9 062.4±393.4 | 9 172.7±405.01 |

| NS组 | 11 866.5±183.8 | 11 107.8±179.7 | 11 835.3±191.8 | 11 657.7±160.3 | 12 054.2±180.1 | 12 111.4±206.6 |

| HS组 | 12 016.2±105.7 | 11 976.8±173.1 | 12 011.3±270.7 | 12 489.8±136.9 | 12 515.6±272.8 | 12 028.6±163.2 |

| Peak-dP/dtmax(mmHg/s) | ||||||

| NR组 | 1 553.8±25.7 | 2 113.6±336.9 | 28 871.2±114.2 | 2 335.9±230.2 | 1 923.7±811.2 | 1 880.4±116.6 |

| HP组 | 10 331.3±255.6 | 8 557.6±217.8c | 8 186.1±335.5c | 6 221.6±144.6c | 5 368.8±373.5c | 6 153.4±165.3c |

| HRe30组 | 7 880.1±207.8 | 7 715.6±209.2 | 4 434.7±269.3 | 6 237.3±210.3 | 5 092.7±174.8 | 4 960.1±212.4 |

| HRe90组 | 11 523.1±327.3 | 8 390.1±442.3 | 9 146.7±377.1 | 7 254.9±381.6 | 7 564.0±256.4 | 8 275.4±394.7 |

| NS组 | 10 570.3±279.4 | 10 971.7±241.8 | 11 010.9±186.2 | 10 133.8±130.3 | 9 667.4±363.8 | 10 003.8±103.5 |

| HS组 | 7 600.3±151.6 | 7 370.0±101.9 | 6 989.0±209.5 | 6 548.8±211.5 | 7 008.1±123.9 | 7 205.5±188.4 |

| 注:与NS组比较,aP < 0.05;与HS组比较,bP < 0.05;与NR组比较,cP < 0.05;与HP组比较,dP < 0.05;与HRe30组比较,eP < 0.05;与HRe90组比较,fP < 0.05 | ||||||

HP组NSE复苏后360 min、600 min低于NR、HRe30和HRe90组(均P < 0.05);NR组Trx复苏后60、120、360、600 min时高于HP、HRe30和HRe90组(均P < 0.05;HP组Trx复苏后60、120、360、600 min时低于HRe30、HRe90(均P < 0.05);NR、HRe30和HRe90组NSE各时间点差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05);HRe30、HRe90组Trx各时间点差异均无统计学意义(均P > 0.05)(表 2)。

| 指标 | CA前15 min | ROSC后 | ||||

| 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 360 min | 600 min | ||

| NSE(μg/L) | ||||||

| NR组 | 143.39±1.10 | 148.48±1.06ab | 150.17±1.71ab | 159.48±1.21ab | 169.59±1.34ab | 171.86±1.27ab |

| HP组 | 126.66±1.57 | 140.99±1.55 | 148.76±1.29 | 131.12±2.08 | 137.74±2.61cdf | 163.13±1.33abcdf |

| HRe30组 | 147.79±1.36 | 152.86±1.40ab | 152.21±1.67ab | 162.51±1.53ab | 166.43±1.21ab | 164.27±1.48ab |

| HRe90组 | 138.55±2.73 | 146.05±2.19ab | 153.83±1.78ab | 148.56±2.00ab | 154.35±2.61 | 169.14±2.93ab |

| NS组 | 148.67±2.03 | 138.49±1.74 | 147.86±1.88 | 151.93±0.97 | 145.43±1.52 | 139.45±1.69 |

| HS组 | 141.97±1.04 | 135.40±1.32 | 146.56±1.29 | 153.30±1.08 | 144.91±1.41 | 142.03±1.37 |

| Trx(ng/L) | ||||||

| NR组 | 170.44±11.58 | 196.98±13.12 | 204.21±12.74def | 210.19±13.22def | 212.37±15.01def | 219.57±14.13def |

| HP组 | 174.21±9.91 | 178.91±10.24 | 183.46±9.86 | 189.30±9.08 | 191.86±10.35 | 207.23±10.71 |

| HRe30组 | 164.19±11.72 | 172.82±12.27 | 186.56±12.18 | 190.17±11.43 | 196.88±12.05 | 210.84±11.44 |

| HRe90组 | 167.41±10.02 | 173.70±11.14 | 184.58±11.55 | 189.60±12.57 | 194.06±11.62 | 215.14±12.43 |

| NS组 | 162.26±9.32 | 168.88±8.98 | 170.47±9.77 | 169.54±7.36 | 173.57±8.01 | 174.08±9.05 |

| HS组 | 165.64±5.10 | 167.01±6.18 | 166.43±5.24 | 170.19±8.65 | 166.36±7.02 | 171.94±6.30 |

| 注:与NS组比较,aP < 0.05;与HS组比较,bP < 0.05;与NR组比较,cP < 0.05;与HP组比较,dP < 0.05;与HRe30组比较,eP < 0.05;与HRe90组比较,fP < 0.05 | ||||||

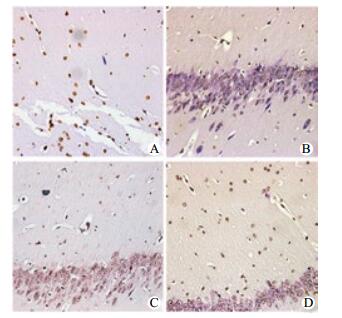

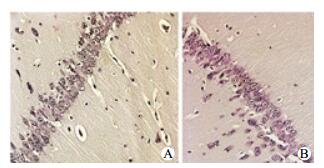

海马CA1区神经元细胞凋亡染色:HS和NS组细胞形态正常,未见凋亡染色;低温复苏组细胞凋亡数量少,染色浅;常温复苏组凋亡细胞明显多,染色深,形态不一,见图 2~3。

|

| A:NR组;B:HP组;C:HRe30组;D:HRe90组 图 2 TUNLE法观察复苏组海马CA1区神经元细胞凋亡情况(DAB×200) Figure 2 Determination of brain cell apoptosis in each group by TUNEL(DAB×200) |

|

|

|

| A:NS组;B:HS组 图 3 TUNLE法观察假手术组海马CA1区神经元细胞凋亡情况(DAB×200) Figure 3 Apoptosis index of intestinal epithelial cell in the sham groups(DAB×200) |

|

|

复苏组AI值高于假手术组,常温复苏组AI值高于亚低温复苏组(均P < 0.05)。HP组AI值低于复苏后低温组(均P < 0.05)(表 3)。

| 组别 | AI(%) |

| NR组 | 62.25±10.43ab |

| HP组 | 20.61±5.02abce |

| HRe30组 | 25.08±3.92abc |

| HRe90组 | 30.33±7.15abc |

| NS组 | 11.13±2.81 |

| HS组 | 9.02±3.02 |

| 注:与NS组比较,aP < 0.05;与HS组比较,bP < 0.05;与NR组比较,cP < 0.05;与HP组比较,dP < 0.05;与HRe30组比较,eP < 0.05 | |

CA已成为重症监护病房(ICU)患者死亡主要元凶之一,2015年CPR指南首次强调将MTH适应人群扩大为所有CA后ROSC成年昏迷患者,且至少维持目标体温24 h。临床实践多在ROSC后才开始行MTH[11-12],此时心、脑组织I/R损伤已产生。MTH已证实通过下列机制改善CA患者生存率和神经功能预后:(1)减轻I/R损伤,减缓细胞内钙超载,抑制氧自由基生成,抑制炎症介质释放等;(2)降低细胞氧耗及ATP消耗速率,保护血脑屏障,调节低灌注区氧供不足与I/R损伤高代谢之间严重不协调等[13]。

随着相关研究不断开展,关于MTH何时启动存在较大争议,即便大多数学者认为越早越好,但尚未形成共识[14-16]。随着医学技术进步及医疗资源配置不断提高,临床很多科室尤其ICU已具备针对高危患者的监护方法和评估手段,ICU医生可及时行MTH,早期开始高级生命支持,进而延长PCAS治疗时间窗。为探究MTH最佳治疗时间窗,本实验根据PCAS分期将低温治疗分别设定在CA前及ROSC后30 min和90 min,并通过检测和观察脑功能及血流动力学指标进行评估。

本实验结果发现,NR组血清NSE及Trx指标在各观察点均明显高于亚低温复苏组。HP组Trx在ROSC后各时间点均低于其他复苏组,而HP组NSE仅在ROSC后360 min、600 min低于其他复苏组。通过比较海马CA1区神经元细胞AI值及光镜下病理学观察发现CA前低温预适应能显著改善I/R损伤对脑功能影响,并改善神经功能预后。由于大脑对缺氧极其敏感,脑组织中氧和能量储存较低,而缺氧对海马CA1区损伤最明显[17-18],因此尽早行脑保护措施对改善预后具有帮助。有学者肯定这一作用并发现亚低温治疗减轻脑水肿及血脑屏障的破坏,而这又可能与紧密连接和黏附连接减少、金属蛋白酶-9和血管内皮生长因子表达增加及血管生成素-1表达上调有关,但有待进一步研究[19]。

PCAS期间脑功能预后情况直接影响患者远期心理及生理康复效果,故改善脑功能及早期系统性评估就显得十分重要。CPR指南建议对未行MTH患者神经功能预后不良评估需在CA发生72 h后进行,为避免MTH过程镇静剂干扰,接受MTH患者则需等到体温恢复正常72 h以后[11]。复苏后患者常采用脑电图判断预后,但预测价值尚未明确,尚缺乏MTH对脑电图和诱发电位影响的研究。临床上,还可通过脑影像学检查及早发现脑部器质性病变[20],但对预后评估还缺乏经验。2013年Mongardon等[21]对CA后行MTH患者血清Trx浓度进行检测,发现Trx作为炎症与氧化应激标志物,测定值与致CA病因严重程度有关。有研究认为Trx对认知功能也有一定影响[22]。因此结合本研究结果考虑其在未来或可成为脑功能损伤评估指标。

本研究证实CA前行MTH可显著保护脑功能,减轻I/R损伤,改善预后[23-24]。其原因可能为(1)尽早达到低温状态,有效降低重要器官基础代谢及氧耗[25],保护线粒体,抑制凋亡,降低细胞代谢构和功能损伤程度。(2)CA前“冷灌注”可降低CA后出现的炎症级联放大反应,减轻组织细胞损伤和脂质过氧化反应,上调海马冷诱导RNA结合蛋白水平[26],降低I/R损伤高峰[27];(3)CA前行MTH可易化除颤,降低阈值,下调炎症基因表达水平[28],能更早恢复心脏泵功能,恢复重要脏器有效灌注。

综上所述,MTH对复苏后脑功能有保护作用,在PCAS急性期及之前行MTH对重要脏器保护作用更佳。但关于MTH临床效果评估(成人、儿童)及作用机制仍需深入研究[29-33]。

| [1] | Absalom AR, Bradley P, Soar J, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in an urban/rural area during 1991 and 1996: have emergency medical service changes improved outcome?[J]. Resuscitation, 1999, 40(1): 3-9. DOI:10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00004-0 |

| [2] | Böttiger BW, Grabner C, Bauer H, et al. Long term outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with physician staffed emergency medical services: the Utstein style applied to a midsized urban/suburban area[J]. Heart, 1999, 82(6): 674-679. DOI:10.1136/hrt.82.6.674 |

| [3] | Herlitz J, Bahr J, Fischer M, et al. Resuscitation in Europe: a tale of five European regions[J]. Resuscitation, 1999, 41(2): 121-131. DOI:10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00045-3 |

| [4] | McNally B, Stokes A, Crouch A, et al. CARES: cardiac arrest registry to enhance survival[J]. Ann Emerg Med, 2009, 54(5): 674-683.e2. DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.018 |

| [5] | 贾海燕, 李来传, 袁洲杰, 等. 亚低温对心肺复苏后脑神经功能的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2011, 20(2): 219-220. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2011.02.032 |

| [6] | 李雄文. 复苏后综合征47例临床分析[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2002, 14(4): 235-236. DOI:10.3760/j.issn.1003-0603.2002.04.019 |

| [7] | 曹雯, 李培杰, 张立平, 等. 亚低温疗法对复苏后家兔心肌的保护作用[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2012, 21(6): 622-625. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2012.06.015 |

| [8] | Takagi Y, Mitsui A, Nishiyama A, et al. Overexpression of thioredoxin in transgenic mice attenuates focal ischemic brain damage[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1999, 96(7): 4131-4136. DOI:10.1073/pnas.96.7.4131 |

| [9] | Idris AH, Becker LB, Ornato JP, et al. Utstein-style guidelines for uniform reporting of laboratory CPR research: a statement for health care professionals from a Task Force of the American Heart Association, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American College of Cardiology, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Institute of Critical Care Medicine, the Safar Center for Resuscitation Research, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine[J]. Ann Emerg Med, 1996, 28(5): 527-541. DOI:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70117-8 |

| [10] | 廖晓星, 胡春林, 文洁, 等. 兔心肺复苏后经腹腔诱导亚低温的研究[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2010, 19(1): 16-20. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2010.01.005 |

| [11] | Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, et al. Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care[J]. Circulation, 2015, 132(18 Suppl 2): S465-482. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000262 |

| [12] | 李壮丽, 邵敏, 李跃东. 亚低温治疗对心搏骤停心肺复苏后患者脑保护作用的研究进展[J]. 中国中西医结合急救杂志, 2017, 24(1): 101-103. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-9691.2017.01.031 |

| [13] | 宿志宇, 李春盛. 低温疗法在心肺脑复苏中的研究进展[J]. 中国危重病急救医学, 2010, 22(2): 119-122. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-0603.2010.02.023 |

| [14] | Frank F, Broessner G. Is there still a role for hypothermia in neurocritical care?[J]. Curr Opin Crit Care, 2017, 23(2): 115. DOI:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000398 |

| [15] | 李俊, 商波, 陆芹芹, 等. 心脏骤停后综合征集束化治疗的研究[J]. 中国急救医学, 2014, 34(12): 345-347. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-6966.2014.04.021 |

| [16] | 花嵘, 李春盛. 亚低温用于心搏骤停后脑保护的研究进展[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2010, 19(10): 1109-1111. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2010.10.033 |

| [17] | Busto R, Dietrich WD, Globus MY, et al. Postischemic moderate hypothermia inhibits CA1 hippocampal ischemic neuronal injury[J]. Neurosci Lett, 1989, 101(3): 299-304. DOI:10.1016/0304-3940(89)90549-1 |

| [18] | Dietrich WD, Busto R, Alonso O, et al. Intraischemic but not postischemic brain hypothermia protects chronically following global forebrain ischemia in rats[J]. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 1993, 13(4): 541-549. DOI:10.1038/jcbfm.1993.71 |

| [19] | Li J, Li C, Yuan W, et al. Mild hypothermia alleviates brain oedema and blood-brain barrier disruption by attenuating tight junction and adherens junction breakdown in a swine model of cardiopulmonary resuscitation[J]. PloS One, 2017, 12(3): e0174596. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0174596 |

| [20] | 王淦楠, 张劲松. 心搏骤停后昏迷患者神经功能预后评估的研究进展[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2016, 25(5): 687-690. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2016.05.031 |

| [21] | Mongardon N, Lemiale V, Borderie D, et al. Plasma thioredoxin levels during post-cardiac arrest syndrome: relationship with severity and outcome[J]. Crit Care, 2013, 17(1): R18. DOI:10.1186/cc12492 |

| [22] | 马一嘉, 房辉, 李玉凯, 等. 2型糖尿病患者血清Trx、Txnip与认知功能的相关性[J]. 中国现代医学杂志, 2017, 27(3): 59-63. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2017.03.012 |

| [23] | Pang PY, Wee GH, Ming JH, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia may improve neurological outcomes in extracorporeal life support for adult cardiac arrest[J]. Heart Lung Circ, 2017, 26(8): 817-824. DOI:10.1016/j.hlc.2016.11.022 |

| [24] | Italian Cooling Experience (ICE) Study Group. Early-versus late-initiation of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: Preliminary observations from the experience of 17 Italian intensive care units[J]. Resuscitation, 2012, 83(7): 823. DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.12.002 |

| [25] | 黄达, 梁剑峰, 朱曦, 等. 心脏骤停复苏后患者体温对脑功能预后的影响[J]. 临床麻醉学杂志, 2016, 32(6): 567-572. |

| [26] | 吴淋, 高宇, 惠康丽, 等. 低温对心搏骤停大鼠心肺复苏后海马CRIP表达的影响[J]. 中华麻醉学杂志, 2016, 36(2): 235-238. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1416.2016.02.029 |

| [27] | 陈镭, 刘晓智, 李罡, 等. 亚低温影响受损神经元蛋白质组改变的研究[J]. 中华神经外科杂志, 2015, 31(8): 846-850. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-2346.2015.08.023 |

| [28] | Shi J, Dai W, Kloner RA. Therapeutic hypothermia reduces the inflammatory response following ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat hearts[J]. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag, 2017, 7(3): 162-170. DOI:10.1089/ther.2016.0042 |

| [29] | Ummarino D. Cardiac resuscitation: Hypothermia or normothermia?[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2017, 14(3): 130. DOI:10.1038/nrcardio.2017.17 |

| [30] | 魏红艳, 胡春林, 李欣, 等. 亚低温对兔心肺复苏后凝血及脑微循环的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2011, 20(3): 259-263. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2011.03.011 |

| [31] | 王义辉, 金奇, 邹雅茹, 等. 亚低温治疗犬心脏骤停复苏后心功能研究[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2014, 23(9): 993-997. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2014.09.011 |

| [32] | 张浙, 肖盐, 刁孟元, 等. PI3K/AKt/GSK3β信号通路在复苏中颈部降温的脑保护作用[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2017, 26(5): 554-559. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2017.05.014 |

| [33] | 魏红艳, 廖晓星, 李欣, 等. 腹腔降温对心肺复苏后兔海马神经损伤的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2012, 21(10): 1116-1121. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2012.10.011 |

2018, Vol. 27

2018, Vol. 27