2. 广东省第二人民医院呼吸与危重症医学科,广州 510310;

3. 暨南大学,广州 510632;

4. 广东省疾病预防控制中心,广州 511430

2. Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Guangdong Second Provincial General hospital, Guangzhou 510310, China;

3. Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China;

4. Guangdong Provincial Disease Control and Prevention, Guangzhou 511430, China

重症肺炎疾病进展快、预后差、病死率高,在过去十几年里发病率持续升高[1],如何降低重症肺炎病死率、改善预后,仍是一大难题。原因主要有两个方面:一方面是部分重症肺炎患者临床表现不典型,容易漏诊、误诊,早期诊治率不足[2]; 另一方面是感染病原体复杂,而病原学诊断率不足[3],导致精准治疗难以实现。为提高对成人重症肺炎的认识及救治能力,本研究拟对成人重症肺炎患者临床特征进行分析并探讨FilmArray肺炎检测系统在重症肺炎中的作用。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料选取2021年6月至2022年4月广东省第二人民医院收治的145例肺炎患者。重症肺炎诊断参考美国胸科协会与传染病协会(ATS/IDSA)制定的标准[4]; 排除肺结核、间质性肺炎、肺癌、尘肺等疾病、年龄 < 18岁、未进行FilmArray检测的病例。根据是否满足重症肺炎诊断标准分为重症组(63例)和轻症组(82例)。该研究通过广东省第二人民医院医学伦理委员会审核批准(2021-KZ-167-02),所有患者进行气管镜操作前均签署知情同意书。

1.2 研究方法 1.2.1 收集资料通过电子病历系统收集患者基本信息、基础疾病、临床症状、实验室检查、严重程度评分及预后等临床资料。

1.2.2 标本获取及送检由本院呼吸与危重症医学科具有纤维支气管镜操作资格的临床医师严格按照方案[5]与无菌操作完成肺泡灌洗液(bronchoalveolar lavage fluid,BALF)的采集。获取BALF后立即进行FilmArray检测(FilmArray2.0测试仪器及FilmArray肺炎测试条购自法国梅里埃公司),痰、BALF及血样均送往检验医学部微生物实验室进行培养。

1.3 统计学方法采用SPSS 26.0统计软件分析,计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)或M(Q1,Q3)表示,两组间比较采用t检验或Mann-Whitney U检验。计数资料以例(%)表示,两组间比较采用Fisher确切概率法或χ2检验,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 临床特征重症组年龄为(72.67±1.71)岁,男性占84.1%,中位住院时间为16 d,9例发生院内死亡。与轻症组相比,重症组肺炎严重指数评分以Ⅳ、Ⅴ级为主(88.9%),院内获得性肺炎多见(65.1%),临床症状表现为发热、咳嗽、咳痰、气促、胸痛及意识改变,更多合并高血压、糖尿病、脑血管疾病、慢性肾病、肿瘤等基础疾病(P < 0.05)。实验室检查发现重症组白细胞总数(white blood cell count, WBC)、中性粒细胞比率(neutrophil percentage, NE%)、降钙素原(procalcitonin, PCT)、C反应蛋白(C-reactive protein, CRP)高于轻症组,CD3+、CD4+、CD8+细胞计数低于轻症组(均P < 0.05)。见表 1。

| 项目 | 重症肺炎(n=63) | 轻症肺炎(n=82) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 72.67±1.71 | 58.78±2.34 | 4.786 | < 0.001 |

| 男性(例,%) | 53 (84.1) | 46 (56.1) | 12.923 | < 0.001 |

| 体重指数(kg/m2)a | 19.73±3.28 | 20.78±3.89 | −1.695 | 0.092 |

| 肺炎严重指数Ⅳ、Ⅴ级(例,%) | 56 (88.9) | 23 (28.1) | 53.178 | < 0.001 |

| 院内获得(例,%) | 41 (65.1) | 12 (14.6) | 30.093 | < 0.001 |

| 临床症状(例,%) | ||||

| 发热 | 41 (65.1) | 34 (41.5) | 7.957 | < 0.001 |

| 咳嗽 | 55 (87.3) | 76 (92.7) | 1.183 | 0.277 |

| 咳痰 | 55 (87.3) | 65 (79.3) | 1.611 | 0.204 |

| 气促 | 44 (69.8) | 39 (47.6) | 7.226 | < 0.001 |

| 胸痛 | 1 (1.6) | 16 (19.5) | 11.061 | < 0.001 |

| 意识改变 | 24 (38.1) | 4 (4.9) | 25.229 | < 0.001 |

| 基础疾病(例,%) | ||||

| 高血压 | 32 (50.8) | 26 (31.7) | 5.408 | 0.020 |

| 冠心病 | 9 (14.3) | 9 (11.0) | 0.359 | 0.549 |

| 糖尿病 | 20 (31.8) | 8 (9.8) | 11.057 | < 0.001 |

| 脑血管病 | 30 (47.6) | 12 (14.6) | 18.839 | < 0.001 |

| 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 | 9 (14.3) | 12 (14.6) | 0.003 | 0.953 |

| 支气管扩张 | 2 (3.2) | 12 (14.6) | 5.364 | 0.021 |

| 慢性肾病 | 10 (15.9) | 2 (2.4) | 8.470 | 0.004 |

| 肿瘤病史 | 12 (19.1) | 10 (12.2) | 1.300 | 0.254 |

| 长期卧床(例,%) | 31 (49.2) | 6 (7.3) | 32.893 | < 0.001 |

| 住院时间(d)b | 16 (11, 20) | 10 (8, 14) | 4.220 | 0.040 |

| 死亡(例,%) | 9 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | — | < 0.001 |

| 实验室检查b | ||||

| WBC(×109/L) | 11.58 (9.24, 15.36) | 9.51 (6.05, 12.98) | −2.904 | 0.004 |

| NE% | 0.86 (0.79, 0.91) | 0.78 (0.66, 0.85) | −4.162 | < 0.001 |

| PCT(ng/mL) | 0.73 (0.18, 4.88) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.23) | −5.456 | < 0.001 |

| CRP(mg/L) | 79.80 (52.15, 98.60) | 36.95 (3.40, 80.75) | −4.485 | < 0.001 |

| CD3+细胞(个/μL) | 758 (453, 1114) | 922 (647, 1509) | −2.649 | < 0.001 |

| CD4+细胞(个/μL) | 460 (268, 680) | 532 (388, 869) | −2.146 | 0.032 |

| CD8+细胞(个/μL) | 224 (164, 344) | 310 (236, 536) | −3.339 | < 0.001 |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.81 (1.29, 2.57) | 1.89 (1.29, 2.21) | −0.773 | 0.493 |

| 注:WBC为白细胞总数; NE%为中性粒细胞比率; PCT为降钙素原; CRP为C反应蛋白; 淋巴细胞亚群(CD3+细胞、CD4+细胞、CD8+细胞、CD4/CD8); a为(x±s); b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

145例肺炎中有92例为社区获得,排除24例(重症5例、轻症19例)为入院72 h后采集BALF,共121例纳入分析。121份BALF样本进行了FilmArray检测,送检痰培养56份、BALF培养120份、血培养57份。

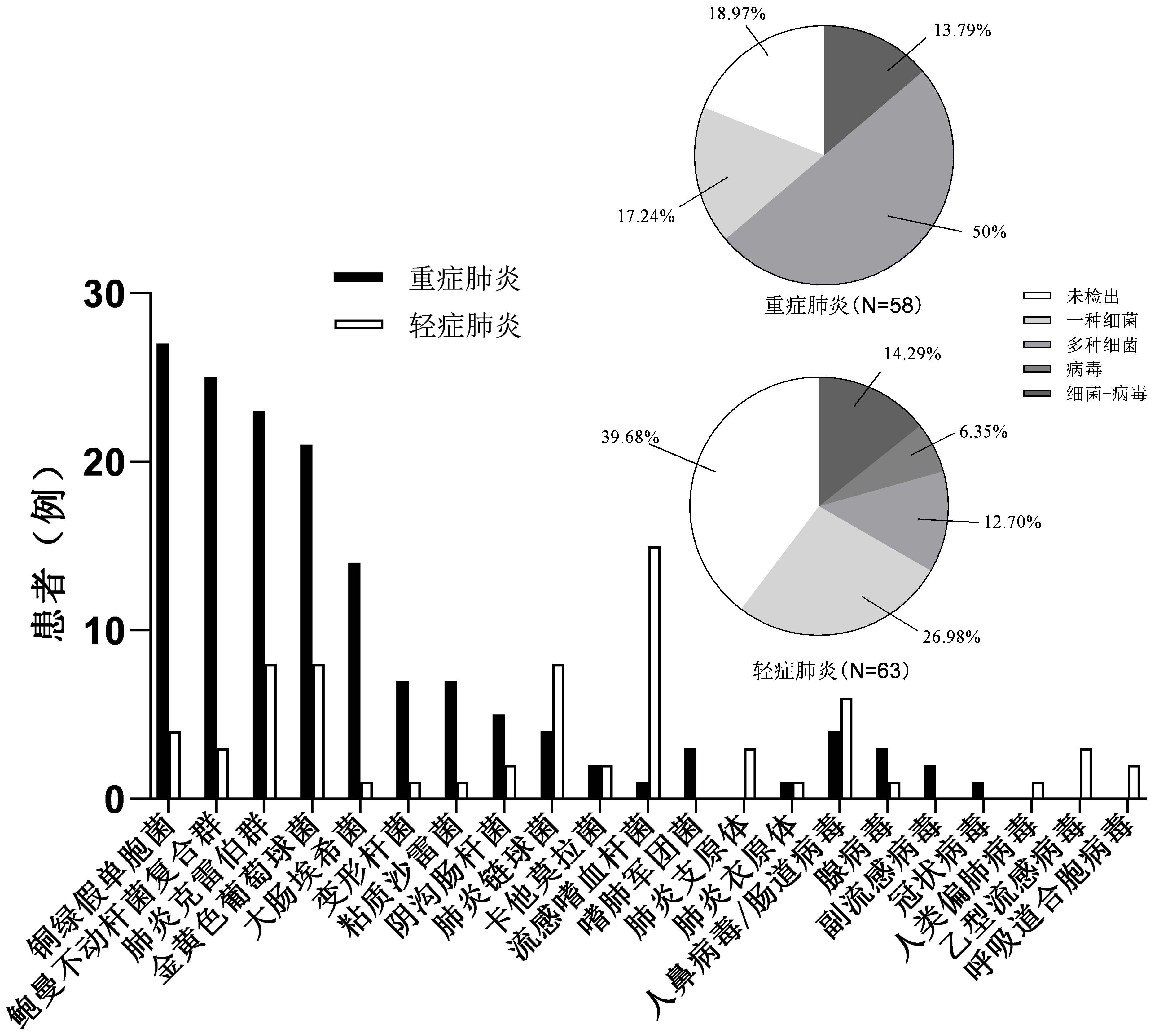

2.2.1 FilmArray检测结果重症组58例患者中47例(81.0%)检测出病原体; 63例轻症组中38例(60.3%)检测出病原体,检出率低于重症组(χ2=6.201,P=0.013)。两组检测出病原体仍以细菌为主:重症组检测出前四位分别为铜绿假单胞菌、鲍曼不动杆菌复合群、肺炎克雷伯菌、金黄色葡萄球菌; 轻症组检测出前四位分别为流感嗜血杆菌、肺炎链球菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、肺炎克雷伯菌。鲍曼不动杆菌复合群、铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、金黄色葡萄球菌及大肠埃希菌在重症组中多见(χ2=24.96、35.613、11.516、9.158、11.566,均P < 0.01),流感嗜血杆菌在轻症组中多见(χ2=12.837,P < 0.01)。重症组中多种细菌混合感染占50%,显著高于轻症组(χ2=18.289,P < 0.01)。重症与轻症组病毒检出率分别为13.8%、20.6%,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见图 1。重症组院内获得性肺炎(severe hospital acquired pneumonia, SHAP)与轻症组HAP病原学分布相似。重症社区获得性肺炎(severe community acquired pneumonia, SCAP)病原学检出前三位为铜绿假单胞菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、肺炎克雷伯菌,病毒检出率为5.9%;轻症CAP病原学检测前四位为流感嗜血杆菌、肺炎链球菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、金黄色葡萄球菌,病毒检出率为23.5%,高于SCAP。重症组患者中41例(70.7%)检测出耐药基因,轻症组11例(17.5%)检测出耐药基因,差异具有统计学意义(χ2=34.914,P < 0.01)。

|

| 图 1 重症肺炎与轻症肺炎病原学检出情况 Fig 1 Pathogenic distribution of severe pneumonia and mild pneumonia |

|

|

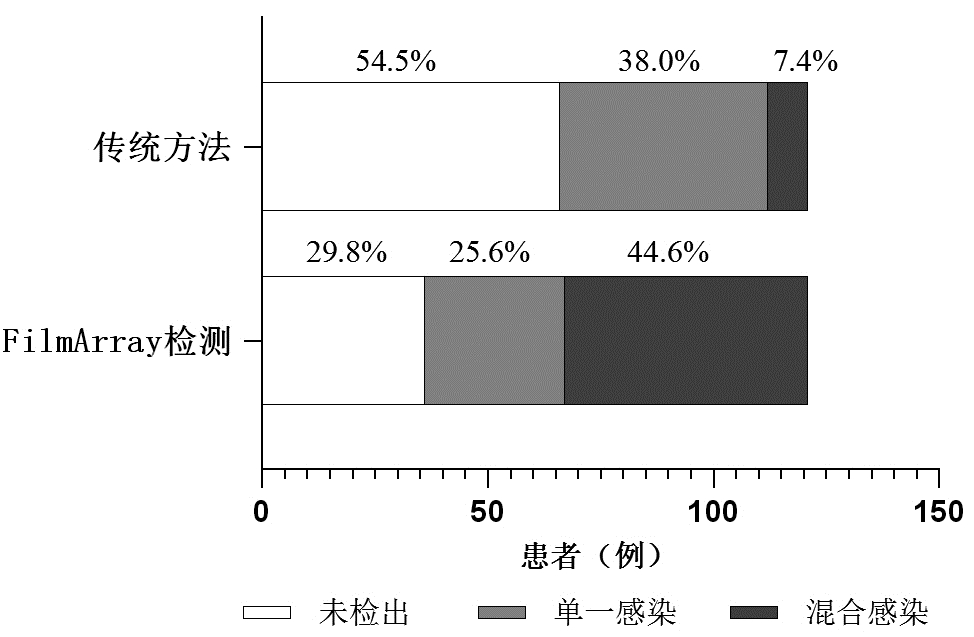

22份痰培养阳性,48份BALF培养阳性,5份血培养阳性,通过传统培养方法共有55例(45.5%)患者检测出病原体,其中46例仅检测出一种病原体,9例检测出多种病原体混合感染。通过FilmArray检测方法,85例检测出病原体,阳性率为70.2%,单一感染31例,混合感染54例。相较于传统培养,FilmArray检测阳性率有所提高(χ2=15.252,P < 0.01),能检测出更多病原体(χ2=30.015,P < 0.01)(图 2)。在重症组中,FilmArray检测阳性率为81%,混合感染占50%,上述结论同样成立。

|

| 图 2 FilmArray检测与传统检测方法病原学构成情况 Fig 2 Pathogenic composition of FilmArray detection and traditional pathogen detection methods |

|

|

重症肺炎发病率及病死率居高不下,这给社会和家庭带来沉重负担[6]。本研究显示重症肺炎以老年男性为主,合并基础疾病多,为重症肺炎感染高危因素[7],临床中应注意筛查; 临床症状表现为发热、咳嗽、咳痰、气促、胸痛及意识改变,部分重症患者仅以气促或意识改变起病,尤其是老年患者常起病隐匿而病情重[8],临床医师需提高警惕,避免漏诊。感染指标WBC、NE%、PCT、CRP升高,提示细菌感染,与本研究病原学结果以细菌为主相符。重症肺炎CD3+、CD4+、CD8+细胞计数低于轻症组,提示免疫状态低下,对这部分患者可给予适当免疫治疗。

多数研究均支持在明确重症感染诊断后尽早启动抗菌治疗[9-11],为避免抗生素滥用,笔者对重症肺炎患者病原学进行监测。BALF作为检测标本更有助于指导抗生素治疗[12],因此本研究选用BALF进行FilmArray检测。研究发现,SHAP与HAP病原学分布差异无统计学意义,常见病原菌为鲍曼不动杆菌复合群、铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、金黄色葡萄球菌,与大多数关于院内获得性肺炎的研究报道相符[13]; SCAP常见病原学为铜绿假单胞菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、肺炎克雷伯菌,而轻症CAP主要以流感嗜血杆菌、肺炎链球菌为主,病毒检出率更高。既往大部分研究都支持肺炎链球菌为社区获得性肺炎最常见致病菌,近几年在不同地区发现肺炎链球菌已不再占主导地位,病毒所占地位在逐渐提高[14-15],本研究显示流感嗜血杆菌检出率最高,病毒检出率达23.5%。不少研究发现轻症CAP与SCAP病原谱分布存在差异[16]; Jain等[17]发现肺炎链球菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、肠杆菌科在重症CAP患者中更常见; Carugati等[18]发现在ICU内CAP中最常见的病原体为肺炎链球菌、铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌; Kyriazopoulou等[19]发现在具有多重耐药(multidrug resistance, MDR)感染高危因素的SCAP患者中检出病原体前三位分别是铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、金黄色葡萄球菌,这与本研究结果类似。本研究SCAP肺炎链球菌检出率较低的可能原因为:纳入患者多为老年,基础疾病多,免疫力低下,为MDR感染高危因素[17],肺炎链球菌比例低于无MDR感染高危因素的患者[19]。在临床中对于院内获得性肺炎用药时应注意覆盖鲍曼不动杆菌复合群、铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌等常见菌; 而对于社区获得性肺炎需立即评估病情严重程度及是否存在MDR感染高危因素,根据相应的常见病原菌进行针对性用药; 重症肺炎中混合感染及耐药基因检出率高,注意联合用药及覆盖耐药菌株。

本研究发现FilmArray病原检出率显著高于传统方法,阳性率为70.2%,与既往研究(72.2%~76.1%)基本一致[19-20]; 在重症组中阳性率为81%,混合感染占50%,弥补了传统培养阳性率低、耗时长、未能同时检测多种病原体等不足,有助于指导临床用药。

本研究存在以下局限性:(1)样本量较少,为单中心研究; (2)FilmArray检测靶标有限,未覆盖到真菌; (3)未对药敏结果进行分析,检测出耐药基因是否与药敏结果一致有待进一步研究。

综上所述,重症肺炎病情复杂,临床医师需对患者一般情况、基础疾病、免疫状态及实验室检查结果等进行综合评估; 病原学分布以细菌为主,多为混合感染,FilmArray肺炎检测系统在重症肺炎快速诊断中具有一定作用。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 刘丽红:实验操作、数据收集及整理、统计学分析、论文撰写; 刘莹、李苑莹、刘镜:实验操作; 屈满英:留取标本、论文修改; 柯昌文:技术及材料支持、指导; 孙瑞琳:研究设计、论文修改、基金支持

| [1] | Laporte L, Hermetet C, Jouan Y, et al. Ten-year trends in intensive care admissions for respiratory infections in the elderly[J]. Ann Intensive Care, 2018, 8(1): 84. DOI:10.1186/s13613-018-0430-6 |

| [2] | 瞿介明, 曹彬. 中国成人社区获得性肺炎诊断和治疗指南(2016年版)[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2016, 39(4): 253-279. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2016.04.005 |

| [3] | 邹晓辉, 曹彬. 呼吸道感染病原学诊断年度进展[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2022, 45(1): 78-82. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20211116-00809 |

| [4] | Salih W, Schembri S, Chalmers JD. Simplification of the IDSA/ATS criteria for severe CAP using meta-analysis and observational data[J]. Eur Respir J, 2014, 43(3): 842-851. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00089513 |

| [5] | 中华医学会呼吸病学分会. 肺部感染性疾病支气管肺泡灌洗病原体检测中国专家共识(2017年版)[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2017, 40(8): 578-583. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2017.08.007 |

| [6] | Hu YZ, Han YT, Yu CQ, et al. The hospitalization burden of all-cause pneumonia in China: a population-based study, 2009-2017[J]. Lancet Reg Health West Pac, 2022, 22: 100443. DOI:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100443 |

| [7] | Ticinesi A, Nouvenne A, Folesani G, et al. An investigation of multimorbidity measures as risk factors for pneumonia in elderly frail patients admitted to hospital[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2016, 28: 102-106. DOI:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.11.021 |

| [8] | 刘昕, 奚桓, 徐钢, 等. 老年与非老年新型冠状病毒肺炎临床特征比较[J]. 中华老年医学杂志, 2021, 40(11): 1381-1385. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-9026.2021.11.009 |

| [9] | Prescott HC, Seelye S, Wang XQ, et al. Temporal trends in antimicrobial prescribing during hospitalization for potential infection and sepsis[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2022, 182(8): 805-813. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2291 |

| [10] | Liu VX, Fielding-Singh V, Greene JD, et al. The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in sepsis[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2017, 196(7): 856-863. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201609-1848OC |

| [11] | Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 376(23): 2235-2244. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1703058 |

| [12] | 邵飞飞, 梁琦强, 肖纬, 等. 支气管肺泡灌洗对重症肺炎抗生素使用的影响[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2019, 28(12): 1529-1532. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.12.014 |

| [13] | 中华医学会呼吸病学分会感染学组. 中国成人医院获得性肺炎与呼吸机相关性肺炎诊断和治疗指南(2018年版)[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2018, 41(4): 255-280. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2018.04.006 |

| [14] | Walden AP, Clarke GM, McKechnie S, et al. Patients with community acquired pneumonia admitted to European intensive care units: an epidemiological survey of the GenOSept cohort[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(2): R58. DOI:10.1186/cc13812 |

| [15] | Spoorenberg SM, Bos WJ, Heijligenberg R, et al. Microbial aetiology, outcomes, and costs of hospitalisation for community-acquired pneumonia; an observational analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2014, 14: 335. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-14-335 |

| [16] | Karhu J, Ala-Kokko TI, Vuorinen T, et al. Lower respiratory tract virus findings in mechanically ventilated patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(1): 62-70. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu237 |

| [17] | Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(5): 415-427. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1500245 |

| [18] | Carugati M, Aliberti S, Sotgiu G, et al. Bacterial etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent hospitalized patients and appropriateness of empirical treatment recommendations: an international point-prevalence study[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2020, 39(8): 1513-1525. DOI:10.1007/s10096-020-03870-3 |

| [19] | Kyriazopoulou E, Karageorgos A, Liaskou-Antoniou L, et al. BioFire® FilmArray® pneumonia panel for severe lower respiratory tract infections: subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial[J]. Infect Dis Ther, 2021, 10(3): 1437-1449. DOI:10.1007/s40121-021-00459-x |

| [20] | Ginocchio CC, Garcia-Mondragon C, Mauerhofer B, et al. Multinational evaluation of the BioFire® FilmArray® Pneumonia plus Panel as compared to standard of care testing[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2021, 40(8): 1609-1622. DOI:10.1007/s10096-021-04195-5 |

2022, Vol. 31

2022, Vol. 31