脓毒症是感染引起的表现为宿主全身炎症反应的一种致命的临床综合征,全球病死率极高,在病程发展过程中,随着血管内皮受损,凝血系统被广泛激活,消耗大量凝血因子,从而导致机体微血管内广泛的发生凝血,形成微血栓,最终造成弥漫性血管内凝血(disseminated intravascular coagulation, DIC)。因此,理解炎症和微血栓形成之间的关联可预防疾病的发生和提早干预。除了目前临床常规凝血实验的检测外,血栓弹力图(thrombelastography,TEG)作为评估重症患者凝血功能的常规工具,已在脓毒症性DIC、创伤性凝血病、新型冠状病毒性肺炎等危重症中得到了广泛的应用[1-2]。本研究通过对脓毒症患者早期血栓弹力图进行监测,探讨脓毒症患者凝血功能的早期变化以及与其严重程度及预后的相关性。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料回顾性分析2013年1月1日-2019年12月31日期间于上海市交通大学附属瑞金医院急诊ICU及急诊内科病房收治的行TEG检测的脓毒症患者。

1.1.1 纳入标准采用2016年SSC拯救脓毒症指南标准[3]进行脓毒症的诊断,同时符合存在临床感染以及存在脏器功能衰竭的SOFA评分≥2的患者诊断为脓毒症; 年龄≥18岁且≤85岁的患者,满足急性起病,出现临床症状至入院时间≤7 d,入院24 d内行炎症指标及TEG检测,同时行APECHEⅡ评分予以入组。

1.1.2 排除标准符合以下任意一项予以排除:妊娠、哺乳期者; 有血液系统疾病(包括急慢性白血病、溶血性贫血、血友病、再生障碍性贫血、骨髓纤维化、先天性或获得性凝血因子缺乏等); 抗凝药物或抗血小板药物治疗中; 处于严重创伤或外科手术后24 h; 自身免疫性疾病; 肝硬化; 恶性肿瘤个人史或正在接受放化疗及靶向治疗的恶性肿瘤患者。

1.2 观察指标患者入院24 h内留取静脉血,行血生化以及TEG的检测,TEG检测用含0.3 mL 109 mmol /L枸橼酸钠抗凝管抽取入组患者全血1管,全血用于TEG检测,采用血栓弹力图凝血分析仪(TEG©5000TEG) 及其试剂盒(批号,HMO4061) (美国Haemonetics公司),检测内容包括:α角、综合凝血指数、K时间、最大血块强度(maximum amplitude,MA)以及R时间五个指标。根据24 h内临床指标最差值计算APACHE Ⅱ及SOFA评分。患者入院后接受脓毒症规范治疗,并记录患者28 d院内病死率、重症转化率等相关数据。

1.3 研究方法根据APACHE Ⅱ评分系统得分情况分为轻症组和重症组[4]: 轻症组(≤13分)、重症组(>13分)进行病程分级,观察不同组间凝血功能指标的差异; 观察脓毒症患者死亡组与存活组之间TEG的差异,从而判断TEG对预后的判断价值。

本研究为回顾性观察性单中心研究,已通过上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院伦理委员会伦理审查,同意患者豁免知情同意进行临床研究。编号(2020)临伦审第(398)号。

1.4 统计学方法采用SPSS 22.0软件以及MedCalc 20软件进行数据统计分析。正态分布的计量数据采用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,偏态分布的计量数据则采用中位数(四分位数间距)[M(QR)]表示。不同预后两组患者间的数据比较采用成组t检验(正态分布)或者非参数检验(偏态分布)。比较不同严重程度的脓毒症患者的TEG的差异以及TEG对脓毒症患者死亡预后的判断价值比较采用两样本秩和检验Mann-Whiteney U检验。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。TEG对脓毒症死亡预后的评估采用绘制受试者工作特征曲线(ROC)。

2 结果 2.1 基本情况共纳入符合入组标准患者共147例,其中男性82例,女性65例; 年龄(58.3±17.6)岁; 按照APECHEⅡ评分将患者分为轻、重两组,轻度脓毒症组共38例; 重度脓毒症组109例,重度脓毒症组中死亡22例; 轻度与重度脓毒症组中,在性别、感染部位以及平均住院天数方面均差异无统计学意义; 而轻度组在年龄方面比重度组年龄小,差异有统计学意义,见表 1。

| 指标 | 脓毒症 | 轻度 | 重度 | χ2 / t /Z值 | P值 |

| 例数(n) | 147 | 38 | 109 | ||

| 男(n, %) | 82(55.8) | 21(55.3) | 61(56.0) | 0.006 | 0.940 |

| 年龄(岁, x±s) | 58.3±17.6 | 47.5±19.1 | 62.1±15.5 | 3.915 | 0.001 |

| 感染部位(n, %) | |||||

| 呼吸 | 60(40.8) | 12(31.6) | 48(44.0) | 6.602 | 0.159 |

| 消化 | 53(36.1) | 19(50.0) | 34(31.2) | ||

| 泌尿道 | 19(12.9) | 2(5.3) | 17(15.6) | ||

| 中枢 | 3(2) | 1(2.6) | 2(1.8) | ||

| 其他 | 12(8.2) | 4(10.5) | 8(7.3) | ||

| 平均住院天数(d, x±s) | 26.4±19.7 | 22.7±16.7 | 27.5±24.0 | 1.352 | 0.247 |

| 死亡(n) | 22 | 0 | 22 |

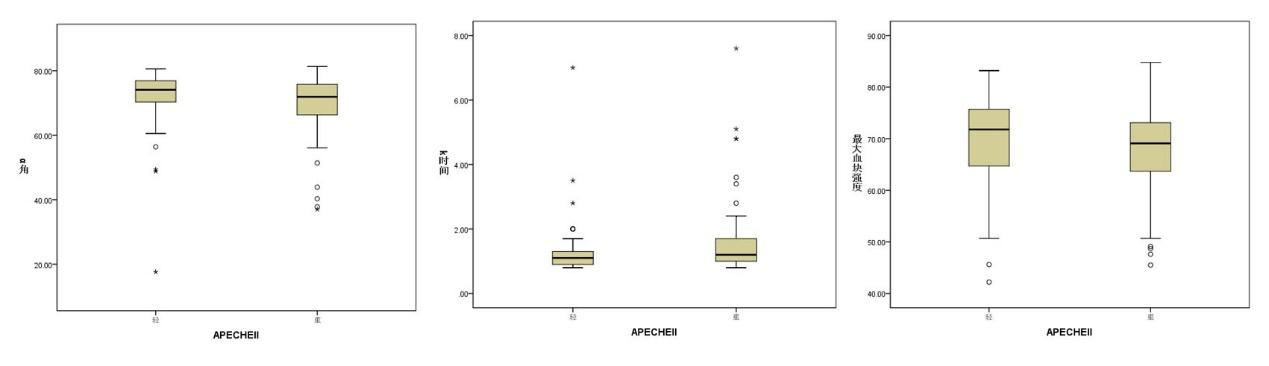

应用非参数秩和检验发现,不同严重程度间的脓毒症患者的TEG指标中α角、K时间以及最大血块强度之间差异有统计学意义。即重度的脓毒症较轻度的脓毒症其α角减小、K时间明显延长,最大血块强度增强,见表 2及图 1。

| 组别 | α角(º) | 综合凝血指数(CI) | K时间(min) | 最大血块强度 | R时间(min) |

| 轻度组 | 74.1(6.7) | 2.8(2.0) | 0.7(0.2) | 66.4(9.60) | 5.1(1.5) |

| 重度组 | 71.9(9.6) | 2.1(2.8) | 1.4(0.3) | 71.8(11.1) | 5.0(1.7) |

| Z值 | -2.438 | -1.691 | 2.426 | 2.007 | -.104 |

| P值 | 0.015 | 0.091 | 0.015 | 0.045 | 0.917 |

|

| 图 1 不同严重程度脓毒症患者α角、K时间和最大血块强度的差异 Fig 1 The difference of α angle, K time and maximum amplitude in patients with different severity of sepsis |

|

|

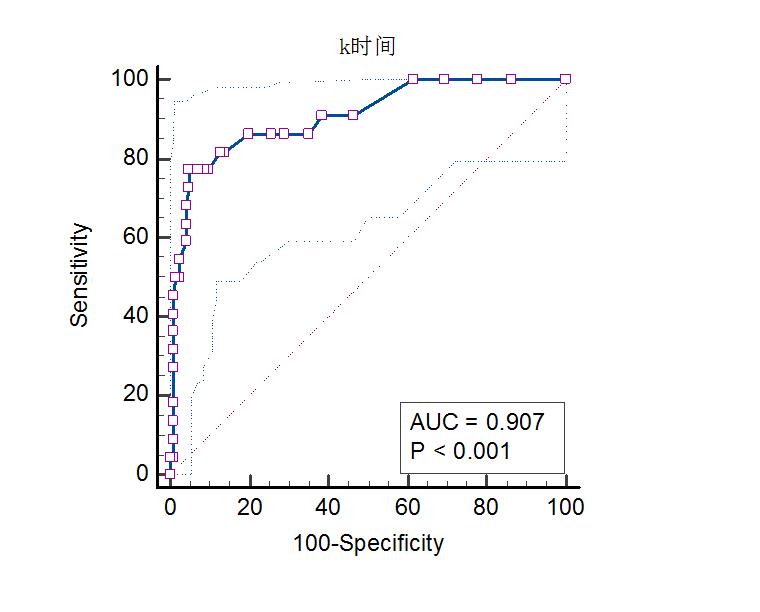

在对脓毒症患者死亡组与存活组的TEG研究分析中发现,K时间在存活组与死亡组之间差异有统计学意义(P<0.001),即可判定脓毒症死亡组的K时间明显大于存活组的K时间。而其余指标包括α角、综合凝血指数、最大血块强度以及R时间在两组间差异无统计学意义,见表 3。

| 组别 | α角(º) | CI | k时间 | 最大血块强度(min) | R时间(min) |

| 存活组(n=125) | 72.1(9.2) | 2.1(2.75) | 1.2(0.7) | 67.5(11.2) | 5.1(1.8) |

| 死亡组(n=22) | 71.4(8.2) | 2.3(3.9) | 3.4(2.6) | 69.5(11.2) | 4.9(1.7) |

| Z | -0.027 | -0.014 | -6.101 | -0.508 | -1.095 |

| P值 | 0.978 | 0.989 | P<0.001 | 0.612 | 0.274 |

通过受试者曲线用K时间对脓毒症的死亡组进行评估发现,当K时间≥2.2 min时(此时敏感度为77.27%,特异度为95.20%;曲线下面积为0.907,95%CI为0.848~0.949)时,可判断脓毒症发生死亡的风险最大,诊断存在统计学意义(P < 0.01),见图 2。

|

| 图 2 K时间用于判断脓毒症患者死亡的ROC曲线 Fig 2 ROC curve of k time for prediction of mortality |

|

|

脓毒症患者的凝血功能异常是一个动态且复杂的过程,脓毒症的患者有倾向于发生血栓型弥散性血管内凝血(DIC)的风险,其可由病原相关分子模式(pathogen-associated molecular pattern,PAMP)或损伤相关分子模式(damage-associated molecular pattern,DAMP)引起系统性炎症及内皮损伤,继而形成大量凝血酶活化、抗凝及纤溶活性抑制,最终导致广泛微血栓形成及多器官功能衰竭[5-6]。而整个过程的发生是迅速的,且临床症状隐蔽,因此给诊断带来了一定的挑战性。

通过常规凝血功能以及血栓弹力图(TEG)可以尽早期的发现脓毒症患者凝血功能的异常及其特点。TEG自20世纪80年代中后期开始用于临床,目前已经在急危重症领域得到了广泛的应用[7]。相较于传统的常规凝血检测无法评估凝血的全貌,TEG全血检测综合了凝血过程中血浆成分(凝血因子、纤维蛋白)和细胞组分(血小板),与凝血机制的三个阶段相吻合,同时还检测了纤溶状态[8-10]。TEG主要检测指标有:代表纤维蛋白原功能的α角及k时间,代表血小板和纤维蛋白原聚集功能的最大血块强度,代表凝血因子活性的R时间、以及代表纤溶功能的30 min时溶解度(LY30%)。有报道称TEG指标的异常与疾病严重程度相关[11-13]。

国外有研究[14]表明,脓毒症患者的K时间与非脓毒症患者相比明显延长,同时α角与MA值明显减小,这种在疾病初期阶段显示出的低凝状态是入院30 d病死率的独立危险因素。另有研究报道[9, 15]称TEG参数与INR等传统的凝血指标相比存在诊断上的优势,本研究也发现TEG对脓毒症的严重程度及预后有重要的判断价值。本研究显示重症脓毒症患者较轻症患者的α角减小、K时间明显延长,最大血块强度增强。进一步通过受试者工作曲线发现K时间是判断脓毒症预后的十分有效的参数,当K时间≥2.2 min时,脓毒症患者死亡的风险最高。

K时间的长短主要受纤维蛋白原水平高低的影响,最大血块强度主要受纤维蛋白原及血小板两个因素的影响,其中血小板的作用(约占80%)要比纤维蛋白原(约占20%)大[16-17],血小板质量或数量的异常都会影响到最大血块强度值[18],因此K时间的延长合并最大血块强度的减少表现为低凝状态,可能原因为内毒素导致内皮细胞功能受损,促进凝血酶活化,激活释放各种细胞因子、凝血因子以及血管收缩物质,从而激发血小板聚集,消耗大量凝血底物及凝血酶,从而表现为低凝消耗状态[19-20]。

研究显示脓毒症的早期可出现一过性的高凝,随着血凝块的形成,凝血因子和纤维蛋白原被大量消耗[21],代表纤维蛋白原功能的α角减小及K时间延长与此有关。既往研究发现[22],与未休克患者相比,发生休克的脓毒性患者早期已表现出明显的低凝状态,同时合并血小板的消耗以及纤维蛋白的减少。而另有研究也发现[23-24],处于低凝状态的脓毒症患者发生器官衰竭的概率明显升高,与本研究发现的重度脓毒症患者 α角减小及K时间延长,及K时间延长患者死亡风险增加相一致。

近期有研究发现[25],脓毒症患者的凝血指标INR与其1年期病死率相关。本研究通过对脓毒症患者死亡组与存活组的TEG研究分析中发现,脓毒症死亡组的K时间明显大于存活组的K时间,在这当中考虑仍然是纤维蛋白原的激活,激活血栓形成,凝血功能启动时主要原因。目前较少研究TEG是否与脓毒症患者的长期生存率有关,Luo等[14]发现最大血块强度大于43.65 mm时脓毒症患者死亡风险最高,可能原因是最大血块强度受血小板的作用影响较大,其同样在血栓形成,严重反应以及免疫应激方面起到了重要的作用有关。

综上所述,本研究通过对不同严重程度以及结局的脓毒症患者的TEG监测发现,重症患者的α角减小、K时间明显延长,最大血块强度增强。脓毒症死亡患者的K时间明显高于存活患者,当K时间≥2.2 min时,脓毒症患者死亡的风险最高。因此,TEG对脓毒症患者的严重程度以及预后评判方面仍有研究预测价值,可以做到早期识别,从而尽早调整治疗方案,改善患者的预后。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 陈培莉:论文撰写; 赵冰、马丽:实验设计; 宁宁:数据收集及整理、统计学分析; 毛恩强、盛慧球:研究设计、论文修改

| [1] | Hu YL, McRae HL, Refaai MA. Efficacy of viscoelastic hemostatic assay testing in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation[J]. Eur J Haematol, 2021, 106(6): 873-875. DOI:10.1111/ejh.13617 |

| [2] | Hartmann J, Ergang A, Mason D, et al. The role of TEG analysis in patients with COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: a systematic review[J]. Diagnostics (Basel), 2021, 11(2): 172. DOI:10.3390/diagnostics11020172 |

| [3] | Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43(3): 304-377. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6 |

| [4] | Chen FG, Koh KF. Septic shock in a surgical intensive care: validation of multiorgan and APACHE Ⅱ scores in predicting outcome[J]. Ann Acad Med Singap, 1994, 23(4): 447-451. |

| [5] | Popescu NI, Lupu C, Lupu F. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and its immune mechanisms[J]. Blood, 2022, 139(13): 1973-1986. DOI:10.1182/blood.2020007208 |

| [6] | Levi M, Poll TV. Coagulation in patients with severe sepsis[J]. Semin Thromb Hemost, 2015, 41(1): 9-15. DOI:10.1055/s-0034-1398376 |

| [7] | Cannon JW, Dias JD, Kumar MA, et al. Use of thromboelastography in the evaluation and management of patients with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care Explor, 2021, 3(9): e0526. DOI:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000526 |

| [8] | Müller MC, Meijers JC, Vroom MB, et al. Utility of thromboelastography and/or thromboelastometry in adults with sepsis: a systematic review[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(1): R30. DOI:10.1186/cc13721 |

| [9] | Bhattacharyya A, Tewari P, Gupta D. Comparison of thromboelastography with routine laboratory coagulation parameters to assess the hemostatic profile and prognosticate postoperative critically ill patients[J]. Ann Card Anaesth, 2021, 24(1): 12-16. DOI:10.4103/aca.ACA_162_19 |

| [10] | Yao RQ, Ren C, Ren D, et al. Development of septic shock and prognostic assessment in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease outside Wuhan, China[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2021, 12(4): 293-298. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.04.007 |

| [11] | Terada R, Ikeda T, Mori Y, et al. Comparison of two point of care whole blood coagulation analysis devices and conventional coagulation tests as a predicting tool of perioperative bleeding in adult cardiac surgery-a pilot prospective observational study in Japan[J]. Transfusion, 2019, 59(11): 3525-3535. DOI:10.1111/trf.15523 |

| [12] | Whiting P, Al M, Westwood M, et al. Viscoelastic point-of-care testing to assist with the diagnosis, management and monitoring of haemostasis: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis[J]. Health Technol Assess, 2015, 19(58): 1-228. DOI:10.3310/hta19580 |

| [13] | 刘慧强, 曾庆波, 宋景春, 等. 血栓弹力图与Centuryclot凝血仪监测重症患者凝血功能比较研究[J]. 临床军医杂志, 2019, 47(4): 387-389. DOI:10.16680/j.1671-3826.2019.04.21 |

| [14] | Luo CZ, Hu HB, Gong J, et al. The value of thromboelastography in the diagnosis of Sepsis-induced coagulopathy[J]. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost, 2020, 26: 1076029620951847. DOI:10.1177/1076029620951847 |

| [15] | 王莉, 李波, 王枭, 等. 分析急性重症创伤患者凝血功能障碍与病情严重程度及预后的关系[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2020, 29(6): 826-828. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2020.06.017 |

| [16] | Luddington RJ. Thrombelastography/thromboelastometry[J]. Clin Lab Haematol, 2005, 27(2): 81-90. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2005.00681.x |

| [17] | Zheng R, Pan H, Wang JF, et al. The association of coagulation indicators with in-hospital mortality and 1-year mortality of patients with sepsis at ICU admissions: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2020, 504: 109-118. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2020.02.007 |

| [18] | 陈晨松, 方俊杰, 陈乾峰, 等. 早期血小板计数动态变化对脓毒症患者预后的预测价值[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2022, 31(5): 665-671. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2022.05.017 |

| [19] | Schöchl H, Frietsch T, Pavelka M, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis after major trauma: differential diagnosis of lysis patterns and prognostic value of thrombelastometry[J]. J Trauma, 2009, 67(1): 125-131. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e31818b2483 |

| [20] | Iba T, Arakawa M, Di Nisio M, et al. Newly proposed Sepsis-induced coagulopathy precedes international society on thrombosis and haemostasis overt-disseminated intravascular coagulation and predicts high mortality[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2020, 35(7): 643-649. DOI:10.1177/0885066618773679 |

| [21] | Prakash S, Verghese S, Roxby D, et al. Changes in fibrinolysis and severity of organ failure in sepsis: a prospective observational study using point-of-care test: ROTEM[J]. J Crit Care, 2015, 30(2): 264-270. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.10.014 |

| [22] | Gando S. Microvascular thrombosis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome[J]. Crit Care Med, 2010, 38(2 Suppl): S35-S42. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9e31d |

| [23] | Dhainaut JF, Shorr AF, Macias WL, et al. Dynamic evolution of coagulopathy in the first day of severe sepsis: relationship with mortality and organ failure[J]. Crit Care Med, 2005, 33(2): 341-348. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000153520.31562.48 |

| [24] | Yin J, Chen Y, Huang JL, et al. Prognosis-related classification and dynamic monitoring of immune status in patients with sepsis: a prospective observational study[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2021, 12(3): 185-191. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.03.004 |

| [25] | Haase N, Ostrowski SR, Wetterslev J, et al. Thromboelastography in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective cohort study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2015, 41(1): 77-85. DOI:10.1007/s00134-014-3552-9 |

2022, Vol. 31

2022, Vol. 31