2. 上海交通大学儿科危重病研究所 200062

2. Institute of Pediatric Critical Care, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200062, China

急性呼吸窘迫综合征(acute respiratory distress syndrome,ARDS)是两肺弥漫性炎性渗出、血管外肺水含量(extravascular lung water,EVLW)增加、肺顺应性下降及肺通气减少为病理生理特征的危重症[1]。一项涉及50个国家的459个重症监护病房的LUNG-SAFE研究报告,ARDS的住院病死率高达35%~46%[2]。2015年儿童急性肺损伤国际会议推荐重度ARDS患儿在机械通气无法维持气体交换时可以采用ECMO挽救[3]。传统病情评估手段如肺部影像学(X线或CT扫描)、氧合指数(oxygenation index,OI)、动脉血氧分压/吸入氧体积分数(PaO2/FiO2)等在ECMO治疗过程中实施存在困难。目前超声已被广泛应用于急危重症病情评估[4]。最新研究发现肺部超声评分(lung ultrasound score,LUS)可精确评估ARDS肺部病变的严重度[5-6],但床旁LUS对ARDS患儿在ECMO治疗过程中病情及预后评估较少报道[7]。本文纳入2016年1月至2019年12月上海交通大学附属儿童医院重症医学科(pediatric intensive care unit, PICU)收治的26例ECMO挽救的重度ARDS患儿,前瞻性探讨LUS分值与病情及预后的关系,报道如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为前瞻性研究,纳入2016年1月至2019年12月在上海交通大学附属儿童医院PICU收治的患重度ARDS、经肺保护性通气策略等治疗病情继续加重而使用ECMO救治、并采用LUS监测肺部病变的患儿。

1.1.1 纳入标准符合柏林标准[8]诊断的重度ARDS,经肺保护性通气治疗、保守液体管理、神经肌肉接头阻滞剂和俯卧位等综合治疗,仍不能维持合适的正常氧合水平。参考国际体外生命支持组织儿童ECMO呼吸支持指南建议[9],进行ECMO挽救治疗。

1.1.2 排除标准(1)ECMO治疗时间 < 3 d;(2)因胸部外伤、或过分肥胖等缺乏合适声窗的患者;(3)存在气胸;(4)继发于先天性心血管疾病或慢性肺部疾病的患者。

研究经医院伦理委员会批准(2016R011-E02),所有检查均取得家属知情同意。

1.2 肺部超声评估方法患者取仰卧位、侧卧及俯卧位,由腋前线及腋后线将胸壁划分为前、侧及后三个区域,每个区域分为上和下两部分,用13-6 MHz线阵探头(M-Turbo便携式彩色超声, Mini-Dock-M Series, 美国索诺声公司)垂直于胸壁表面对12个区域依次进行纵向扫描[10-11]。所有肺部超声检查及视频资料, 均由两名经过专业培训的PICU医师完成。

对12个区域依次进行评分,每个区域以最严重的表现进行评分,分值0~3分,所得的LUS评分为每个区域评分总和,分值0~36分。超声评分定义[12]:(1)正常通气(0分),肺滑动征伴A线或少于2个单独的B线;(2)中度肺通气减少区(1分),多发、典型B线(B1线);(3)重度肺通气减少区(2分),多发融合的B线(B2线);(4)肺实变区(3分),组织影像伴典型的支气管充气征。

1.3 观察指标一般临床资料包括年龄、性别、身体质量指数(body mass index, BMI)、第三代小儿死亡危险评分(PRISM Ⅲ)、ECMO参数、肺动态顺应性(pulmonary dynamic compliance,Cdyn)、肺功能情况(包括PaO2/FiO2、OI和PaCO2)、ECMO和机械通气时间、PICU住院时间等。开始ECMO治疗时行肺部LUS为LUS-0 h,ECMO治疗后24 h、48 h、72 h、第7 d及撤机时,分别为LUS-24 h、LUS-48 h、LUS-72 h、LUS-7 d及LUS-w。

1.4 统计学方法采用SPSS 17.0软件进行统计学分析。计数资料采用频数和百分率表示,应用卡方检验进行两组间差异比较;偏态分布计量资料以中位数(四分位数)[M(QL,QU)]表示,应用Mann-Whitney U检验进行两组间差异分析。采用受试者工作曲线特征(receiver operating characteristic,ROC)曲线及Kaplan-Meier生存曲线分析各指标与PICU病死率之间的关系。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般资料如表 1所示,同期PICU采用ECMO挽救重度ARDS患儿40例。其中14例未纳入研究为:ECMO挽救 < 3 d撤离1例,合并胸部外伤缺乏合适超声窗2例,合并严重气漏5例,合并先天性心血管疾病4例,合并慢性肺疾病1例,过分肥胖1例。最终纳入研究26例。根据出院时生存状态,分为存活组(18例)及死亡组(8例),住院存活率69.2%。存活组与死亡组在年龄、BMI、ECMO启动时的PRISM Ⅲ评分、PaO2/FiO2、OI、PaCO2、Cdyn等差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05)。

| 指标 | 存活组(n=18) | 死亡组(n=8) | Z/χ2值 | P值 |

| 年龄(月)a | 37(10,59) | 15(6,96) | -0.028 | 0.978 |

| 男性(例,%) | 7(38.9) | 5(62.5) | 1.242 | 0.265 |

| BMI a | 14.0(13.1,16.9) | 15.2(14.0,17.7) | -1.000 | 0.317 |

| PRISM Ⅲ a | 19(13,22) | 23(12,37) | -1.005 | 0.315 |

| ARDS原因(例,%) | ||||

| 重症肺炎 | 13(72.2) | 8(100.0) | 2.751 | 0.097 |

| 脓毒症 | 5(27.8) | 0(0.0) | 2.751 | 0.097 |

| 并发症(例,%) | ||||

| 休克 | 13(72.2) | 8(100.0) | 2.751 | 0.097 |

| 急性肾损伤 | 14(77.8) | 6(75.0) | 0.024 | 0.877 |

| 胃肠障碍 | 12(66.7) | 8(100.0) | 3.467 | 0.063 |

| 肝功能障碍 | 10(55.6) | 6(75.0) | 0.885 | 0.347 |

| 凝血功能障碍 | 10(55.6) | 6(75.0) | 0.885 | 0.347 |

| 呼吸力学指标 | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2(mmHg)a | 63.0(53.8,72.5) | 50.4(46.0,66.0) | -1.642 | 0.101 |

| OI a | 28.0(20.0,39.0) | 42.0(30.0,60.0) | -1.747 | 0.081 |

| PaCO2(mmHg)a | 52.5(46.5,62.5) | 57.0(30.8,76.5) | -0.376 | 0.707 |

| Cdyn(mL/cmH2O·kg)a | 0.40(0.35,0.40) | 0.35(0.31,0.37) | -1.919 | 0.055 |

| ECMO模式 | ||||

| V-A模式(例,%) | 12(66.7) | 7(87.5) | 1.222 | 0.269 |

| V-V模式(例,%) | 6(33.3) | 1(12.5) | 1.222 | 0.269 |

| ECMO时间(h)a | 166(122,265) | 121(76,422) | -0.612 | 0.541 |

| 机械通气时间(h)a | 328(165,504) | 194(87,719) | -1.056 | 0.291 |

| 注:ARDS为急性呼吸窘迫综合征;BMI为身体质量指数;PRISM Ⅲ为第三代儿童死亡危险评分;MODS为多器官功能障碍综合征;PaO2/FiO2为动脉氧分压/吸入氧体积分数;OI为氧合指数;PaCO2为二氧化碳分压;Cdyn为动态肺顺应性;CRRT为持续血液净化治疗;ECMO为体外膜肺;a为M(QL,QU) | ||||

存活组LUS-72 h、LUS-w明显低于死亡组;在治疗72 h后存活组ECMO血流量需求显著低于死亡组;治疗72 h、7 d及撤ECMO时存活组患儿Cdyn较死亡组明显改善,差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)。两组LUS-0 h、LUS-24 h、LUS-48 h、ECMO血流-0 h、ECMO血流-24 h、ECMO血流-48 h、Cdyn-0 h、Cdyn-24 h、Cdyn-48 h及ECMO气流比较均差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05),见表 2。

| 项目 | 存活组 | 死亡组 | Z值 | P值 | ||

| 数值 | 例数 | 数值 | 例数 | |||

| LUS-0 h | 18(16,22) | 18 | 21(18,24) | 8 | -1.398 | 0.162 |

| LUS-24 h | 22(20,27) | 18 | 24(22,28) | 8 | -0.780 | 0.435 |

| LUS-48 h | 20(17,24) | 18 | 22(18,27) | 8 | -1.261 | 0.207 |

| LUS-72 h | 16(13,19) | 18 | 26(24,29) | 8 | -3.647 | <0.01 |

| LUS-7 d | 14(12,15) | 9 | - | 3 | - | - |

| LUS-w | 11(10,13) | 18 | 30(26,35) | 8 | -4.026 | <0.01 |

| ECMO血流(mL/kg·min) | ||||||

| ECMO-0 h | 84(72,90) | 18 | 85(73,110) | 7 | -0.364 | 0.716 |

| ECMO-24 h | 73(64,87) | 18 | 90(55,105) | 7 | -0.969 | 0.333 |

| ECMO-48 h | 79(60,89) | 18 | 102(42,133) | 7 | -1.090 | 0.276 |

| ECMO-72 h | 60(44,82) | 18 | 88(74,120) | 7 | -2.362 | 0.018 |

| ECMO-7 d | 55(35,65) | 9 | - | 3 | - | - |

| ECMO气流(L/min) | ||||||

| ECMO-0 h | 2.00(1.20,2.13) | 18 | 2.00(1.00,3.50) | 7 | -0.031 | 0.975 |

| ECMO-24 h | 1.50(1.00,2.00) | 18 | 1.80(1.20,3.50) | 7 | -1.037 | 0.300 |

| ECMO-48 h | 1.65(1.00,2.03) | 18 | 1.50(1.00,3.50) | 7 | -0.640 | 0.522 |

| ECMO-72 h | 1.50(1.00,2.03) | 18 | 1.50(0.70,4.00) | 7 | -0.517 | 0.605 |

| ECMO-7 d | 1.50(0.65,2.00) | 9 | - | 3 | - | - |

| Cdyn(mL/cmH2O·kg) | ||||||

| Cdyn-0 h | 0.40(0.35,0.40) | 18 | 0.35(0.31,0.37) | 8 | -1.919 | 0.055 |

| Cdyn-24 h | 0.34(0.32,0.40) | 18 | 0.31(0.30,0.33) | 8 | -1.737 | 0.082 |

| Cdyn-48 h | 0.40(0.36,0.42) | 18 | 0.39(0.31,0.42) | 8 | -0.898 | 0.369 |

| Cdyn-72 h | 0.48(0.42,0.54) | 18 | 0.36(0.29,0.40) | 8 | -3.182 | 0.001 |

| Cdyn-7 d | 0.60(0.52,0.67) | 13 | 0.27(0.13,0.30) | 4 | -2.962 | 0.003 |

| Cdyn-w | 0.66(0.62,0.70) | 18 | 0.30(0.13,0.35) | 8 | -4.015 | <0.01 |

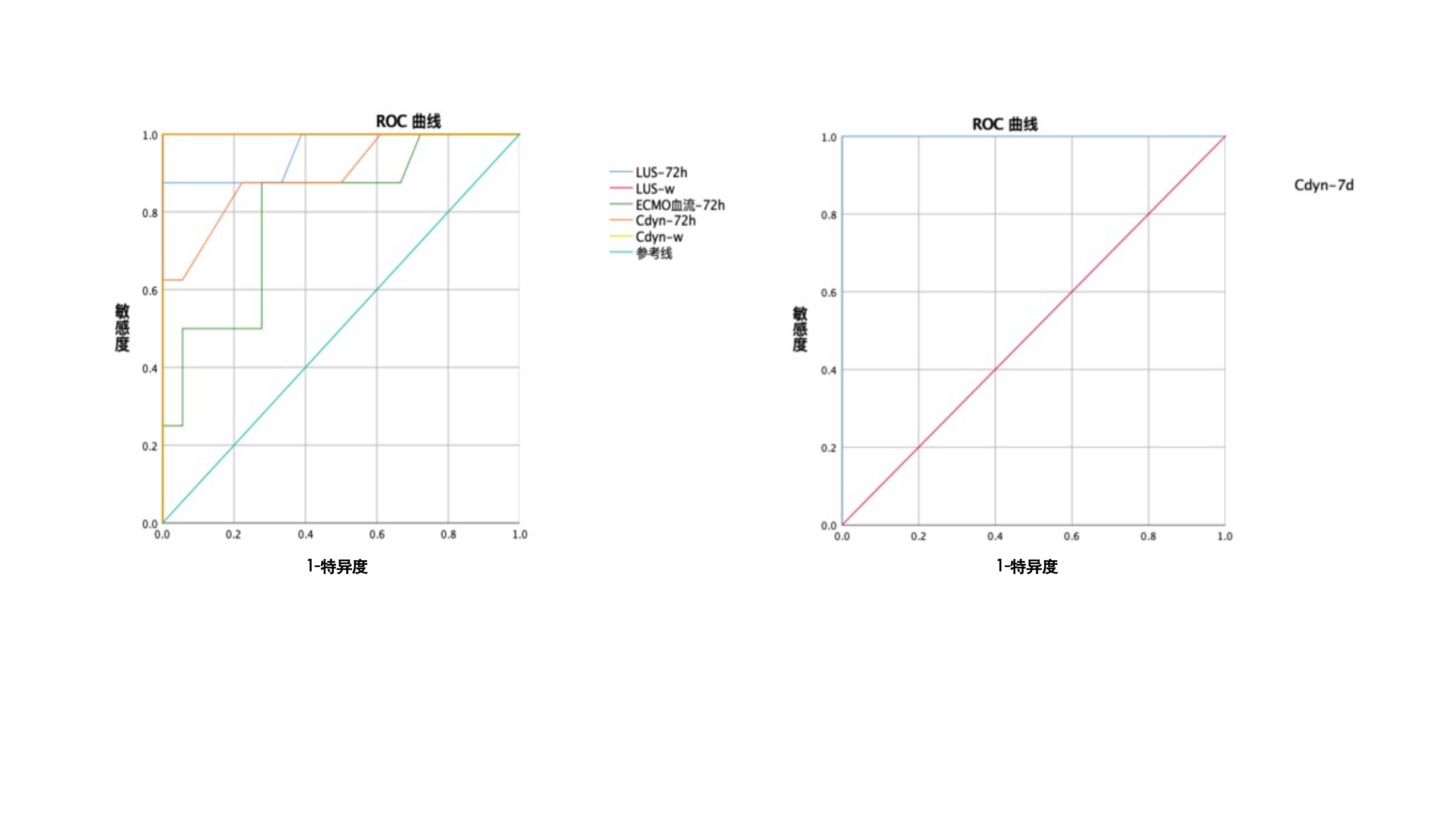

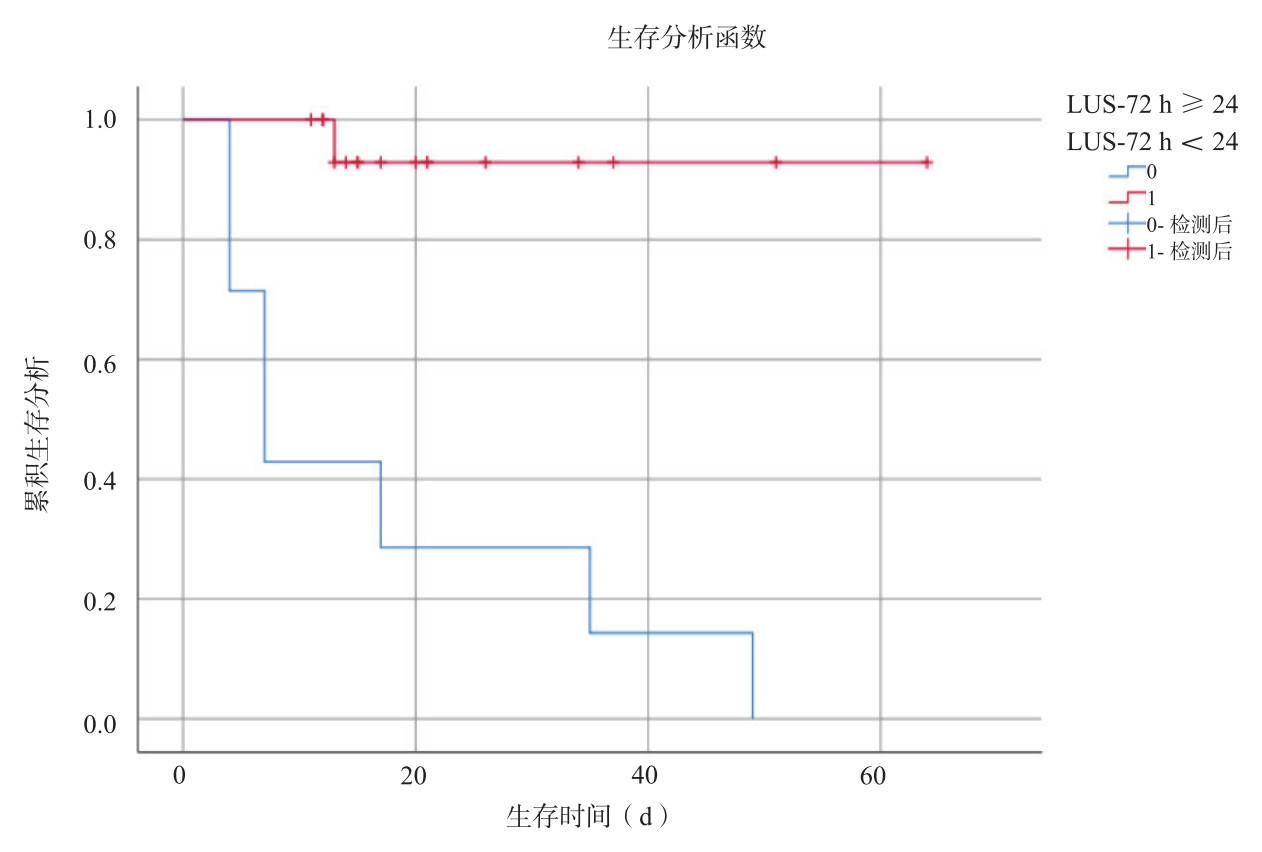

采用ROC曲线分析LUS评分、ECMO血流和Cdyn预测ECMO支持的重度ARDS患儿PICU生存状态的价值,发现LUS-72 h(AUC:0.955,95%CI:0.864~1.000,P < 0.01)、LUS-w(AUC:1.000,95%CI:1.000~1.000,P < 0.01)、ECMO血流-72 h(AUC:0.795,95%CI:0.606~0.984,P=0.018)、Cdyn-72 h(AUC:0.896,95%CI:0.754~1.000,P=0.002)、Cdyn-7 d(AUC:1.000,95%CI:1.000~1.000,P=0.003)、Cdyn-w(AUC:1.000,95%CI:1.000~1.000,P < 0.01)见图 1和表 3。因AUC > 0.9预测重度ARDS患儿PICU生存状态准确性较高,且相对于LUS-w、Cdyn-w和Cdyn-7 d而言,LUS-72 h能更早预测患儿PICU生存状态,得出LUS-72 h截断值为24,灵敏度87.5%,特异度100.0%,以LUS-72 h≥24和LUS-72 h < 24进行分组,经Kaplan-Meier曲线分析提示,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01,见图 2)。

|

| 图 1 ROC曲线预测重度ARDS患儿PICU生存状态的价值 Fig 1 The value of ROC curve in predicting PICU survival in children with severe ARDS |

|

|

| 指标 | AUC | 95%CI | P值 | 灵敏度(%) | 特异度(%) |

| LUS-72 h | 0.955 | 0.864~1.000 | < 0.01 | 87.5 | 100.0 |

| LUS-w | 1.000 | 1.000~1.000 | < 0.01 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| ECMO血流-72 h | 0.795 | 0.606~0.984 | 0.018 | 100.0 | 69.2 |

| Cdyn-72 h | 0.896 | 0.754~1.000 | 0.002 | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| Cdyn-7 d | 1.000 | 1.000~1.000 | 0.003 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Cdyn-w | 1.000 | 1.000~1.000 | < 0.01 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 注:AUC为受试者工作特征曲线下面积;95%CI为95%可信区间。 | |||||

|

| 图 2 Kaplan-Meier生存曲线对比LUS-72 h≥24 vs LUS-72 h < 24重度ARDS患儿的PICU生存状态 Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curve compared PICU survival status of LUS-72h≥24 vs LUS-72 h < 24 in children with severe ARDS |

|

|

床旁超声LUS评分对应于肺部每个区域的评分之和(范围为0~36),能动态、快速、半定量监测ARDS肺通气和肺含水量变化[5-6]。本研究通过动态测定重度ARDS患儿在ECMO治疗过程中LUS评分,发现死亡组在ECMO治疗72 h后LUS评分明显高于存活组(P < 0.05),并观察到ECMO治疗72 h后的LUS评分≥24分,是预测ECMO支持重度ARDS患儿预后的有效参考指标。

根据2012年柏林标准和2015年儿童急性肺损伤共识会议的推荐,PaO2/FiO2和OI [FiO2×平均气道压(Paw)×100]/PaO2仍然是目前对ARDS病情严重程度分级的经典指标[3, 8]。但在ECMO治疗过程中,需计算患者自身肺氧合功能与ECMO支持之间所占比例,无法通过PaO2/FiO2和OI精准评估呼吸衰竭程度和肺部病变。虽然胸部CT检查一直被认为是用来评估ARDS患者肺部形态学及定量分析肺组织通气的金标准[13-14],但转运风险、辐射损伤、较高的成本等缺陷均不适用于危重症患儿。肺部超声是基于失调的气-液比例定义各类病理征象。床旁肺部超声具有易操作、可重复性强、无辐射等优点,能动态、及时发现肺部病情改变。由于射线投射角度偏差、病灶过小、传统射线剂量不足等原因,在ICU中相对于床旁胸片而言,床旁肺部超声的灵敏度更高[15-16]。

弥漫性肺泡损伤,促炎因子释放引起血管内皮和肺泡上皮受损,出现肺水肿、毛细血管渗漏、肺弥散障碍、严重的通气/血流比例失调、肺容积减少是ARDS的主要特点[17-19]。LUS评分可通过对12个胸壁区域依次扫描得到评分总和对肺部病变进行半定量评估。已有研究证实LUS评分可半定量评估肺水含量,指导呼吸机撤离,早期诊断呼吸机相关性肺炎(ventilator-associated pneumonia,VAP),且能对COVID-19相关ARDS患者进行病情评估[20-23]。本组对26例ECMO支持的重度ARDS患儿动态监测LUS评分,发现能替代常规胸部X线或CT检查,掌握患儿肺部病变与含水量的变化。在ECMO治疗72 h后存活组LUS评分已明显低于死亡组。进一步将两组患儿单因素组间比较有统计学差异的指标行ROC曲线分析显示LUS-72 h (AUC=0.955,灵敏度:87.5%,特异度:100.0%)能有效预测患儿预后,优于传统呼吸力学指标。通过Kaplan-Meier生存曲线分析发现,LUS-72 h≥24时患儿住院存活率明显降低(P < 0.01)。因此,ECMO治疗72 h的LUS评分是重度ARDS患儿预后预测的有效指标。本研究观察到LUS分值也能为临床液体管理和其他治疗(使用利尿剂或肾脏替代治疗)提供依据。

在ECMO支持重度ARDS患儿的动态LUS监测中,也存在一些局限性。例如需要对患儿进行翻动时应特别防止重要血管通路的移位,增加ECMO常规管理的负担。特别肥胖或严重气漏时,计算LUS分值可能不准,因此在40例ECMO支持ARDS患者中,仅纳入26例进行分析总结。其他不足是未能同步评估ECMO支持期间LUS与心血管功能指标之间的关系。

综上所述,本研究对26例患儿在ECMO治疗过程中动态监测LUS评分,发现LUS能弥补其他影像学检查的不足,比较准确掌握肺部病变的变化,并可作为预后判断的参考指标。在今后进一步研究中,仍需扩大样本量进行分层分析。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] | Kim WY, Hong SB. Sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome: recent update[J]. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul), 2016, 79(2): 53-57. DOI:10.4046/trd.2016.79.2.53 |

| [2] | Abe T, Madotto F, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology and patterns of tracheostomy practice in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in ICUs across 50 countries[J]. Crit Care Lond Engl, 2018, 22(1): 195. DOI:10.1186/s13054-018-2126-6 |

| [3] | Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2015, 16(5): 428-439. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000350 |

| [4] | Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(4): 577-591. DOI:10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4 |

| [5] | See KC, Ong V, Tan YL, et al. Chest radiography versus lung ultrasound for identification of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective observational study[J]. Crit Care, 2018, 22(1): 203. DOI:10.1186/s13054-018-2105-y |

| [6] | Pisani L, Vercesi V, van Tongeren PSI, et al. The diagnostic accuracy for ARDS of global versus regional lung ultrasound scores - a post hoc analysis of an observational study in invasively ventilated ICU patients[J]. Intensive Care Med Exp, 2019, 7(suppl 1): 44. DOI:10.1186/s40635-019-0241-6 |

| [7] | Mongodi S, Pozzi M, Orlando A, et al. Lung ultrasound for daily monitoring of ARDS patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: preliminary experience[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(1): 123-124. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-4941-7 |

| [8] | ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition[J]. JAMA, 2012, 307(23): 2526-2533. DOI:10.1001/jama.2012.5669 |

| [9] | Guidelines for Pediatric Respiratory Failur[DB/OL]. [2020-11-29]. https://www.elso.org/Resources/Guidelines.aspx. |

| [10] | Mongodi S, Bouhemad B, Orlando A, et al. Modified lung ultrasound score for assessing and monitoring pulmonary aeration[J]. Ultraschall Med, 2017, 38(5): 530-537. DOI:10.1055/s-0042-120260 |

| [11] | Chiumello D, Mongodi S, Algieri I, et al. Assessment of lung aeration and recruitment by CT scan and ultrasound in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients[J]. Crit Care Med, 2018, 46(11): 1761-1768. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0000000000003340 |

| [12] | Bouhemad B, Brisson H, Le-Guen M, et al. Bedside ultrasound assessment of positive end-expiratory pressure-induced lung recruitment[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2011, 183(3): 341-347. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201003-0369oc |

| [13] | Mazzei MA, Guerrini S, Cioffi Squitieri N, et al. Role of computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Recenti Prog Med, 2012, 103(11): 459-464. DOI:10.1701/1166.12889 |

| [14] | Cereda M, Xin Y, Hamedani H, et al. Tidal changes on CT and progression of ARDS[J]. Thorax, 2017, 72(11): 981-989. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209833 |

| [15] | Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E, et al. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonography in acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Anesthesiology, 2004, 100(1): 9-15. DOI:10.1097/00000542-200401000-00006 |

| [16] | Staub LJ, Mazzali Biscaro RR, Kaszubowski E, et al. Lung ultrasound for the emergency diagnosis of pneumonia, acute heart failure, and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Emerg Med, 2019, 56(1): 53-69. DOI:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.09.009 |

| [17] | Derwall M, Martin L, Rossaint R. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathophysiology, current clinical practice, and emerging therapies[J]. Expert Rev Respir Med, 2018, 12(12): 1021-1029. DOI:10.1080/17476348.2018.1548280 |

| [18] | Thille AW, Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P, et al. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2013, 187(7): 761-767. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201211-1981oc |

| [19] | Fujishima S. Pathophysiology and biomarkers of acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. J Intensive Care, 2014, 2(1): 32. DOI:10.1186/2052-0492-2-32 |

| [20] | Bataille B, Rao G, Cocquet P, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound B-lines score and E/Ea ratio to estimate extravascular lung water and its variations in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. J Clin Monit Comput, 2015, 29(1): 169-176. DOI:10.1007/s10877-014-9582-6 |

| [21] | Soummer A, Perbet S, Brisson H, et al. Ultrasound assessment of lung aeration loss during a successful weaning trial predicts postextubation distress[J]. Crit Care Med, 2012, 40(7): 2064-2072. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0b013e31824e68ae |

| [22] | Dargent A, Chatelain E, Kreitmann L, et al. Lung ultrasound score to monitor COVID-19 pneumonia progression in patients with ARDS[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(7): e0236312. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0236312 |

| [23] | 李幼霞, 刘莹, 黄煌, 等. 肺部超声评估经鼻高流量氧疗治疗重型COVID-19患者疗效的价值[J]. 中国急救医学, 2021, 41(5): 397-403. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-1949.2021.05.006 |

2021, Vol. 30

2021, Vol. 30