纳入东阳市人民医院2013.6.1至2020.9.1期间的脓毒症患者900例(入院后诊断为脓毒症),纳入标准:①有明确的感染;②在感染后SOFA评分增加2分及以上,③数据完善。排除标准:①年龄小于18周岁;②肿瘤终末期、白血病、淋巴瘤、免疫缺陷患者(肿瘤终末期患者往往放弃治疗,与其他患者治疗上存在差异;白血病等患者血液指标往往存在异常,与其他患者基线不同,影响统计;免疫缺陷患者在本研究中人数少,且致病微生物复杂,所以以上人群排除)。

1.2 观察指标患者性别、年龄,脓毒症患者入院后第一次心率、平均动脉压,24 h内的第一次下列指标:氧合指数、急诊降钙素原、超敏-C反应蛋白、肌酐、白蛋白、凝血酶原时间、活化部分凝血活酶时间、B型脑钠肽前体、乳酸、酸碱值、红细胞压积、血小板,其中乳酸来自动脉血,其他为静脉血,各单位为目前国际通用单位。

1.3 伦理描述本研究经东阳市人民医院伦理委员会批准,伦理批号:东人医2021-YX-067,取得了患者或者患者家属书面同意。这些数据被匿名分析,个人信息被完全删除。这项研究是根据《赫尔辛基宣言》及其修正案的原则进行的。

1.4 方法描述收集患者数据后(在excel表格中降钙素原大于100标注为100,B型脑钠肽前体大于35 000标注为35 000),利用R软件visreg函数画出每个指标与死亡之间的关系,并进行指标与死亡之间是否为线性关系进行评估,根据以上2点,将与死亡无线性关系的连续性变量转换成分类变量。

先进行单因素分析,用twogrps函数,该函数自动区分连续性变量是否为正态分布,选择合适的检验方式。对单因素分析有意义的指标进行Logistic分析,分析出与死亡相关的因素进行多重共线检验,利用方差膨胀系数(VIFs)值进行判读,VIFs小于10提示各危险因素之间无明显共线,能用于建模。若VIFs大于10,用删除相关变量的办法解决。排除多重共线后将变量进行逐步回归分析,分析独立危险因素进行建模,画出列线图,列线图是一种能快速、直观、精确展现各变量之间的关系,个性化的计算每个患者的死亡风险的模型展现方式[14]。

从区分度和校正及临床效果三方面对预测模型进行了评价,并予bootstrap法进行了内验证,内验证也从区分度和校正及临床效果三方面进行。

预测模型的区分度是指它是否能够有效区分脓毒症患者是否死亡,通过AUC来评估的。AUC值介于0.5和1.0之间,提示模型有意义,AUC值越接近1,模型的判别能力越好。AUC>0.75表明该模型有良好的辨别能力[15]。

预测模型的校准是指预测概率与观测概率的一致性。本文通过建立校准图进行评估,拟合曲线与标准曲线重叠度高,提示预测效果好,P大于0.05,提示有较好的拟合优度[16]。

模型的临床有效性判断在本文中应用DCA曲线进行评价,解读:纵坐标为评估模型的效益,横坐标为患病风险值,曲线(mod)为模型代表的曲线,以All曲线及None(2条极端曲线)曲线为标准,认为model曲线越远离2条极端曲线,临床意义越好,可对临床产生净获益[17-18]。

最后应用随机森林的方法进行了建模,并与本文模型进行比较。

1.5 统计学方法本研究中连续性变量呈正态分布以均数±标准差(Mean±SD)表示,组间比较采用组t检验,非正态分布予秩和检验,用中位数(四分位数)表示(样本量小于5000);分类变量采用χ2检验,用百分比表示。以上统计均在R软件中完成。

2 结果 2.1 纳入人群基本资料与单因素分析结果本研究中,共纳入900例患者,女347例,男553例,死亡139人,病死率约为15.4%。单因素分析,发现有降钙素原、平均动脉压、肌酐等11项指标与预后相关(见表 1,以P < 0.001为差异有统计学意义)。

| 变量 | 总人数(n = 900) | 存活者(n= 761) | 死亡者(n = 139) | 统计量 | P值 |

| 性别(n, %) | 0.343 | 0.558 | |||

| 男 | 553 (61) | 464 (61) | 89 (64) | ||

| 女 | 347 (39) | 297 (39) | 50 (36) | ||

| 凝血酶原时间(n, %) | 22.354 | < 0.001 | |||

| < 15 s | 349 (39) | 314 (41) | 35 (25) | ||

| 15~25 s | 516 (57) | 425 (56) | 91 (65) | ||

| > 25 s | 35 (4) | 22 (3) | 13 (9) | ||

| 部分活化凝血酶原时间[s, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 46 (40.98, 52.3) | 45.8 (40.9, 51.9) | 47.1 (41.4, 54.15) | 47773 | 0.069 |

| 氧合指数(n, %) | 41.325 | < 0.001 | |||

| > 300 | 459 (51) | 408 (54) | 51 (37) | ||

| < 150 | 61 (7) | 35 (5) | 26 (19) | ||

| 150~300 | 380 (42) | 318 (42) | 62 (45) | ||

| 肌酐(n, %) | 46.336 | < 0.001 | |||

| < 100(μmol/L) | 413 (46) | 377 (50) | 36 (26) | ||

| 100~200(μmol/L) | 329 (37) | 268 (35) | 61 (44) | ||

| 201~300(μmol/L) | 82 (9) | 68 (9) | 14 (10) | ||

| 301~400(μmol/L) | 39 (4) | 22 (3) | 17 (12) | ||

| > 400(umol/L) | 37 (4) | 26 (3) | 11 (8) | ||

| 白蛋白(g/L, Mean ± SD) | 28.42 ± 5.01 | 28.85 ± 4.98 | 26.03 ± 4.47 | 6.712 | < 0.001 |

| 平均动脉压(n, %) | 92.024 | < 0.001 | |||

| 70~105(mmHg) | 725 (81) | 644 (85) | 81 (58) | ||

| < 70(mmHg) | 103 (11) | 54 (7) | 49 (35) | ||

| >105(mmHg) | 72 (8) | 63 (8) | 9 (6) | ||

| 红细胞压积(n, %) | 25.657 | < 0.001 | |||

| 0.3~0.459 | 533 (59) | 477 (63) | 56 (40) | ||

| < 0.3 | 357 (40) | 275 (36) | 82 (59) | ||

| > 0.459 | 10 (1) | 9 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| 降钙素原[ng/L, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 14.95 (2.88, 49.17) | 14.29 (2.46, 46.14) | 17.77 (4.17, 75.82) | 44 581 | 0.003 |

| C-反应蛋白[mg/L, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 167.55 (112.35, 200) | 167.6 (115.6, 200) | 164.5 (77.1, 200) | 55 564 | 0.34 |

| 酸碱值[Median (Q1, Q3)] | 7.4 (7.34, 7.44) | 7.41 (7.36, 7.44) | 7.33 (7.23, 7.41) | 72 305 | < 0.001 |

| 血小板(n, %) | 27.196 | < 0.001 | |||

| 100~300(×109/L) | 519 (58) | 461 (61) | 58 (42) | ||

| < 50(×109/L) | 108 (12) | 75 (10) | 33 (24) | ||

| 50~99(×109/L) | 229 (25) | 188 (25) | 41 (29) | ||

| > 300(×109/L) | 44 (5) | 37 (5) | 7 (5) | ||

| B型脑钠肽前体(例, %) | 50.502 | < 0.001 | |||

| < 2 000 (pg/mL) | 438 (49) | 406 (53) | 32 (23) | ||

| 2 000~10 000 (pg/mL) | 310 (34) | 248 (33) | 62 (45) | ||

| 10 001~20 000 (pg/mL) | 72 (8) | 51 (7) | 21 (15) | ||

| > 20 000 (pg/mL) | 80 (9) | 56 (7) | 24 (17) | ||

| 乳酸[mol/L, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 2.4 (1.5, 4.1) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.4) | 5.1 (2.55, 9.85) | 24 560 | < 0.001 |

| 年龄[岁, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 75 (63, 83) | 74 (62, 83) | 77 (66, 85) | 46 493 | 0.023 |

| 心率[次/min, Median (Q1, Q3)] | 119 (104, 135) | 116 (102, 130) | 135 (120, 155) | 29 963 | < 0.001 |

| 尾注:a连续变量符合正态分布予t检验,用均数加减标准差表示,不符合正态分布予秩和检验,用中位数(四分位数)来描述。分类变量采用χ2检验,百分比描述 | |||||

将单因素分析有意义的指标纳入Logistic回归分析,发现:B型脑钠肽前体、乳酸、白蛋白、氧合指数、平均动脉压、红细胞压积、心率与预后相关(见表 2,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义)。

| 变量 | Coefficient(B)a | SEc | OR值(95%CI) | Wald χ2值 | P值 |

| (Intercept)b | 0.536 | 9.124 | 1.709(2.574×10~8~9.355×107) | 0.003 | 0.953 |

| 凝血酶原时间15~25(s) | 0.108 | 0.267 | 1.114 (0.664~1.893) | 0.163 | 0.686 |

| 凝血酶原时间 > 25(s) | 0.583 | 0.515 | 1.790(0.630~4.810) | 1.277 | 0.258 |

| 氧合指数 < 150 | 1.138 | 0.381 | 3.121(1.460~6.560) | 8.886 | 0.003 |

| 氧合指数150~300 | 0.008 | 0.249 | 1.008(0.616~1.643) | 0.001 | 0.975 |

| 肌酐100~200(μmol/L) | 0.102 | 0.270 | 1.107(0.652~1.885) | 0.142 | 0.706 |

| 肌酐201~300(μmol/L) | -0.450 | 0.442 | 0.637(0.259~1.477) | 1.036 | 0.309 |

| 肌酐301~400(μmol/L) | 0.679 | 0.483 | 1.972(0.708~5.027) | 1.092 | 0.160 |

| 肌酐 > 400(μmol/L) | 0.226 | 0.524 | 1.254(0.435~3.433) | 0.186 | 0.666 |

| 白蛋白(g/L) | -0.070 | 0.025 | 0.932(0.887~0.979) | 7.779 | 0.005 |

| 平均动脉压 < 70(mmhg) | 1.650 | 0.292 | 5.206(2.940~9.251) | 30.970 | < 0.001 |

| 平均动脉压 > 105(mmhg) | 0.248 | 0.419 | 1.281(0.533~2.789) | 0.592 | 0.554 |

| 酸碱值 | -0.628 | 1.216 | 0.534(0.049~5.859) | 0.267 | 0.605 |

| 血小板 < 50(×109/L) | -0.091 | 0.333 | 0.913(0.468~1.733) | 0.075 | 0.784 |

| 血小板50~99(×109/L) | 0.095 | 0.266 | 1.100(0.648~1.845) | 0.128 | 0.721 |

| 血小板 > 300(×109/L) | 0.338 | 0.524 | 1.402(0.465~3.706) | 0.416 | 0.519 |

| B型脑钠肽前体2 000~10 000(pg/mL) | 0.814 | 0.276 | 2.256(1.322~3.907) | 8.720 | 0.003 |

| B型脑钠肽前体10 001~20 000(pg/mL) | 0.892 | 0.393 | 2.440(1.113~5.235) | 5.144 | 0.023 |

| B型脑钠肽前体 > 20 000(pg/mL) | 1.004 | 0.390 | 2.728(1.261~5.843) | 6.625 | 0.010 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L) | 0.159 | 0.039 | 1.172(1.087~1.267) | 16.606 | < 0.001 |

| 心率(次/min) | 0.017 | 0.005 | 1.017(1.008~1.026) | 13.177 | < 0.001 |

| 红细胞压积 < 0.299 | 0.696 | 0.240 | 2.001(1.256~3.230) | 8.398 | 0.004 |

| 红细胞压积 > 0.459 | 0.865 | 1.185 | 2.376(0.113~1.811) | 0.533 | 0.465 |

| 注:a回归系数;b截距;c标准误 | |||||

对Logistic分析有意义的指标进行多重共线检验,结果显示各个变量的VIFs值均小于10,证明各变量之间无明显共线关系,可进行下一步的分析(见表 3)。

| 变量 | VIFs值 |

| B型脑钠肽前体 > 20 000(pg/mL) | 1.161 |

| 白蛋白 | 1.183 |

| B型脑钠肽前体2 000~10 000(pg/mL) | 1.186 |

| 心率 | 1.250 |

| B型脑钠肽前体10 001~20 000(pg/mL) | 1.156 |

| 氧合指数 < 150 | 1.345 |

| 红细胞压积 < 0.3 | 1.121 |

| 氧合指数150~300 | 1.122 |

| 平均动脉压 < 70(mmHg) | 1.082 |

| 红细胞压积 > 0.459 | 1.282 |

| 平均动脉压 > 105(mmHg) | 1.023 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L) | 1.278 |

最后进行逐步回归分析,P小于0.05为有统计学意义,结果显示:B型脑钠肽前体、乳酸、白蛋白、氧合指数、平均动脉压、红细胞压积、心率为独立危险因素(见表 4),纳入建模。

| 变量 | Coefficient(B)a | SEc | OR值(95%CI) | Wald χ2值 | P值 |

| (Intercept)b | -4.112 | 0.971 | 0.016(0.002~0.108) | 17.935 | < 0.01 |

| 氧合指数 < 150 | 1.129 | 0.371 | 3.093(1.479~6.372) | 9.254 | 0.002 |

| 氧合指数150~300 | 0.008 | 0.245 | 1.008(0.621~1.630) | 0.001 | 0.975 |

| 白蛋白(g/L) | -0.067 | 0.024 | 0.935(0.891~0.980) | 7.662 | 0.006 |

| 平均动脉压 < 70(mmHg) | 1.692 | 0.284 | 5.432(3.115~9.504) | 35.545 | < 0.01 |

| 平均动脉压 > 105(mmHg) | 0.303 | 0.407 | 1.354(0.576~2.888) | 0.554 | 0.457 |

| B型脑钠肽前体2 000~10 000(pg/mL) | 0.857 | 0.270 | 2.356(1.405~4.012) | 10.323 | 0.001 |

| B型脑钠肽前体10 001~20 000(pg/mL) | 0.915 | 0.384 | 2.497(1.158~5.254) | 5.670 | 0.017 |

| B型脑钠肽前体 > 20 000(pg/mL) | 1.104 | 0.356 | 3.017(1.490~6.051) | 3.099 | 0.002 |

| 乳酸(mmol/L) | 0.173 | 0.032 | 1.189(1.117~1.268) | 9.604 | < 0.001 |

| 心率(次/min) | 0.017 | 0.005 | 1.017(1.008~1.026) | 13.705 | < 0.001 |

| 红细胞压积 < 0.3 | 0.738 | 0.234 | 2.091(1.327~3.321) | 9.979 | 0.002 |

| 红细胞压积 > 0.459 | 0.817 | 1.156 | 2.264(0.111~16.103) | 0.500 | 0.480 |

| 注:a回归系数;b截距;c标准误 | |||||

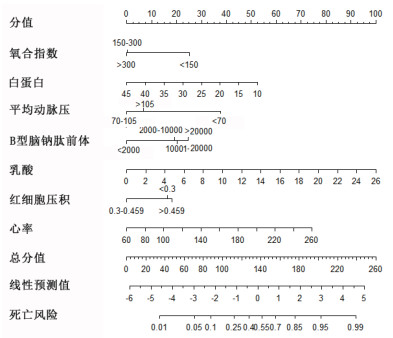

应用独立危险因素建立列线图,见图 1,各独立危险因素具体数值对应相应分值,相加为总分,总分可对应死亡风险。例如:脓毒症患者白蛋白为30 g/L,对应分值约为22.5分;氧合指数大于300,对应分值为0分;平均动脉压为小于70 mmHg,对应分值约为37.5分;B型脑钠肽前体小于2 000 pg/mL,对应分值为0分;乳酸值为6 mmol/L,对应分值约为23分;hct在0.3~0.45之间,对应分值为0分,心率:100次/min,约14分,所有分值相加约为97分,对应死亡风险约为14%。

|

| 图 1 脓毒症患者30 d内死亡风险的列线图 Fig 1 The nomogram of predicting the death risk in patients with sepsis in 30 days |

|

|

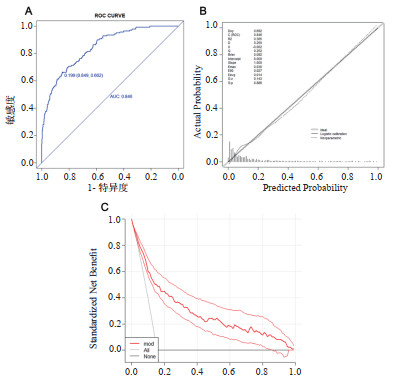

本研究建立了ROC曲线,见图 2A,其AUC为0.846,结果显示该模型显示出良好的辨别能力。模型最佳截点为0.199,特异度为84.9%,敏感度为66.2%;利用校准图进行拟合优度判定,见图 2B,校准图的P值0.886,Brier scaled:0.092,calibration slope:1.000,R2:0.385,提示有良好的拟合;利用DCA(图 2C)曲线进行临床有效性评估,建模曲线(mod)均在两条极端曲线之上,提示有良好的临床意义。

|

| 图 2 建模人群中的ROC曲线、校准图及DCA曲线 Fig 2 The Roc Curve, calibration diagram and DCA curve in model-establishing group |

|

|

|

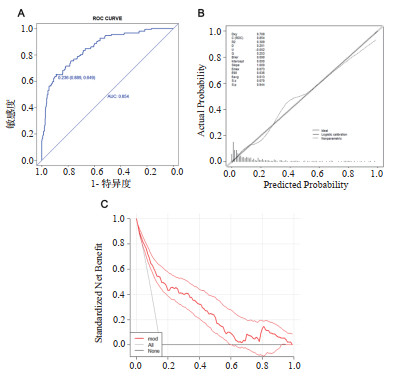

| 图 3 验证人群中的ROC曲线、校准图及DCA曲线 Fig 3 The ROC curve, calibration curve and DCA curve in verification group |

|

|

验证人群AUC:0.854(3A),校准图的P值:0.944,Brier scaled:0.090,calibration slope:1.000,R2:0.389(3B),DCA曲线均在两条极端曲线之上(3C),均提示有良好意义。

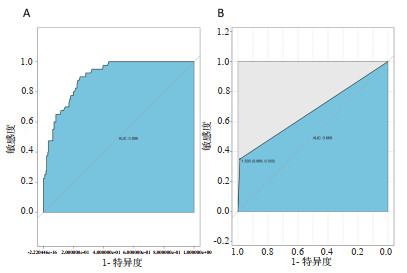

2.8 随机森林建模的结果在建模组中随机森林模型AUC:0.899(4A),提示有较好的分辨能力,在验证组中AUC为0.669(4B),有一定的辨别能力,但效果欠佳。

3 讨论本研究显示患者入院后第一次检测的以下指标:B型脑钠肽前体、乳酸、白蛋白、氧合指数、红细胞压积,及入院时的平均动脉压、心率为脓毒症患者短期预后不良(30 d死亡)的独立危险因素,并且建立了以列线图方式展示的预测模型,该模型为临床医生对脓毒症患者进行预后评价,更好地制定干预措施,促进临床医生与患者家属的沟通提供了参考。模型的区分度、校准度及临床有效性均提示该模型有较好的意义。

|

| 图 4 随机森林建立模型在建模组及验证组中的ROC曲线 Fig 4 The ROC curves of random forest in model-establishing group and validation group |

|

|

凝血障碍[19-20]、呼吸衰竭[21]、急诊降钙素原[22-23]、超敏-C反应蛋白[22]、B型脑钠肽前体[24-25]、肾功能不全[26]、乳酸[27-28]、白蛋白[29]等与脓毒症预后息息相关。本文参考了先前的研究,并根据临床经验,纳入了较容易收集的、可能对预后有影响的变量,分析后得到了与预后相关的独立危险因素。本研究显示,入院后24 h内第1次降钙素原、C-反应蛋白、血小板及凝血、肾功能指标对脓毒症患者短期预后的判断意义比较小。有研究报告降钙素原、C-反应蛋白有助于诊断与判断脓毒症的严重程度[23],但对于是否能用于判断预后是存在争议的,早期的一些大型的研究发现重症感染患者预后与早期降钙素原、C-反应蛋白水平无明显相关性[30]。凝血异常在严重脓毒症患者中常见,凝血异常是脓毒症患者预后不良的指标之一,但迅速纠正凝血能改善预后[19-20],在本研究中,初始显示初始凝血指标不是脓毒症患者短期预后不良的独立危险因素,可能与凝血异常被积极迅速纠正相关。至于肾功能指标的意义,医院CRRT的普及,可能是导致肾功能指标在判断患者预后中的价值大大下降的原因。

乳酸是氧代谢的主要指标之一,乳酸的升高往往提示脓毒症患者出现了循环或者呼吸的不稳定,是疾病恶化的指标,许多脓毒症相关的研究中都有明确的表示乳酸升高是预后不良的指标[27-28]。B型脑钠肽前体是反映心脏功能的指标,脓毒症本身可引起脓毒性心肌病,有研究显示,出现脓毒性心肌病的患者病死率将增加,脓毒症在治疗期间不适当补液也可造成B型脑钠肽前体的上升,无论是本身脓毒症引起或者不适当医疗引起,B型脑钠肽前体的异常增高被认为是脓毒症患者预后不良的指标之一[24-25]。白蛋白是营养指标之一,脓毒症患者消耗增加,若营养不补充到位,将导致预后不良[30]。心率快、平均动脉压低提示脓毒性休克,疾病进入到更加复杂、严重的阶段,有报道指出,脓毒性休克病死率可达到33.5%~61%[31-32]。氧合指数小于300是诊断呼吸衰竭的标准,而研究显示呼吸衰竭是脓毒症患者预后不良的指标[21],另外心脏功能不全及液体复苏的不良反应均可导致氧合指数下降,而上述情况如前述均可导致预后不良。

本研究提示红细胞压积在判断脓毒症患者短期预后上有一定意义,红细胞压积低于正常或者高于正常,均会对预后产生影响,对于脓毒症患者,纠正贫血及者改变血液浓缩状态可以改善预后。上述独立危险因素应引起临床医生的重视,出现异常积极干预,有助于改善脓毒症患者预后。

多年来临床上有许多评分工具被应用于预测脓毒症患者预后,大部分不是针对脓毒症患者开发的,因此在预测脓毒症死亡风险方面存在缺陷,如Arabi等[34]对用于预测ICU脓毒症患者的预后的多个评分系统进行了评价,这些评分系统包括了APACHEⅡ评分、SAPSⅡ(简化急性生理评分)评分等,发现他们的校准都比较差。SOFA评分针对脓毒症患者,但主要用于描述器官功能障碍的发生与发展,对于预测脓毒症患者的死亡,有研究显示SOFA评分的AUC范围为0.69~0.83[34-35],与本研究结果比较,在辨别能力上较差。本研究建立的模型基于脓毒症患者临床资料,更有针对性,在区分及校准、临床有效性方面均有较好的意义,另外本研究模型是基于国内脓毒症患者临床数据,相比较既往研究,更适用于国人。

本研究中,本研究模型与机器学习(随机森林)模型进行了比较,在建模组中AUC为0.899,较本研究模型分辨能力强;但在验证中AUC为0.669,效果欠佳,提示模型稳定性较本研究模型差;另外机器学习模型虽然具有很高的精度,但由于难于解释,它们的效用一直受到严重限制[36-37]。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] | Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated Sepsis.current estimates and limitations[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016, 193(3): 259-272. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201504-0781oc |

| [2] | Group SCCT. Incidence of severe Sepsis and septic shock in German intensive care units: the prospective, multicentre INSEP study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2016, 42(12): 1980-1989. DOI:10.1007/s00134-016-4504-3 |

| [3] | SepNet Critical Care Trials Group. Incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock in German intensive care units: the prospective, multicentre INSEP study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2016, 42(12): 1980-1989. DOI:10.1007/s00134-016-4504-3 |

| [4] | Whittaker SA, Fuchs BD, Gaieski DF, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis admitted to the hospital wards[J]. J Crit Care, 2015, 30(1): 78-84. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.07.012 |

| [5] | Rahmel T. SSC International Guideline 2016 - Management of sepsis and septic shock][J]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther, 2018, 53(2): 142-148. DOI:10.1055/s-0043-114639 |

| [6] | Lu X, Han W, Gao YX, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in immunocompetent patients with septic shock[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2021, 12(2): 124-130. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.02.007 |

| [7] | Yu S, Leung S, Heo M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction scoring systems for ward patients: a retrospective nested case-control study[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(3): R132. DOI:10.1186/cc13947 |

| [8] | Huang CT, Ruan SY, Tsai YJ, et al. Clinical trajectories and causes of death in septic patients with a low APACHEⅡ score[J]. J Clin Med, 2019, 8(7): 1064. DOI:10.3390/jcm8071064 |

| [9] | Zygun DA, Laupland KB, Fick GH, et al. Neuroanesthesia and intensive care limited ability of SOFA and MOD scores to discriminate outcome: a prospective evaluation in 1, 436 patients[J]. Can J Anesth, 2005, 52(3): 302-308. DOI:10.1007/BF03016068 |

| [10] | Phillips GS, Osborn TM, Terry KM, et al. The New York sepsis severity score: development of a risk-adjusted severity model for sepsis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2018, 46(5): 674-683. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0000000000002824 |

| [11] | Zhang ZH, Hong YC. Development of a novel score for the prediction of hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the use of electronic healthcare records with LASSO regression[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(30): 49637-49645. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.17870 |

| [12] | Osborn TM, Phillips G, Lemeshow S, et al. Sepsis severity score: an internationally derived scoring system from the surviving sepsis campaign database[J]. Crit Care Med, 2014, 42(9): 1969-1976. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0000000000000416 |

| [13] | Zhang K, Zhang SF, Cui W, et al. Development and validation of a sepsis mortality risk score for sepsis-3 patients in intensive care unit[J]. Front Med, 2020, 7: 609769. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2020.609769 |

| [14] | Harrell FE. Evaluating the yield of medical tests[J]. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc, 1982, 247(18): 2543-2546. DOI:10.1001/jama.247.18.2543 |

| [15] | Silva TB, Oliveira CZ, Faria EF, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to estimate the risk of prostate cancer in Brazil[J]. Anticancer Res, 2015, 35(5): 2881-2886. |

| [16] | Niu XK, He WF, Zhang Y, et al. Developing a new PI-RADS v2-based nomogram for forecasting high-grade prostate cancer[J]. Clin Radiol, 2017, 72(6): 458-464. DOI:10.1016/j.crad.2016.12.005 |

| [17] | Nattino G, Finazzi S, Bertolini G. A new test and graphical tool to assess the goodness of fit of logistic regression models[J]. Stat Med, 2016, 35(5): 709-720. DOI:10.1002/sim.6744 |

| [18] | Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB, et al. Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers[J]. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 2008, 8: 53. DOI:10.1186/1472-6947-8-53 |

| [19] | Mihajlovic D, Lendak D, Mitic G, et al. Prognostic value of hemostasis-related parameters for prediction of organ dysfunction and mortality in sepsis[J]. Turkish J Med Sci, 2015, 45(1): 93-98. DOI:10.3906/sag-1309-64 |

| [20] | Muzaffar SN, Baronia AK, Azim A, et al. Thromboelastography for evaluation of coagulopathy in nonbleeding patients with sepsis at intensive care unit admission[J]. Indian J Crit Care Med, 2017, 21(5): 268-273. DOI:10.4103/ijccm.ijccm_72_17 |

| [21] | Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43(3): 304-377. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6 |

| [22] | Choe EA, Shin TG, Jo IJ, et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of low procalcitonin levels among patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in the emergency department[J]. Shock, 2016, 46(1): 37-43. DOI:10.1097/shk.0000000000000566 |

| [23] | Yin J, Chen Y, Huang JL, et al. Prognosis-related classification and dynamic monitoring of immune status in patients with sepsis: a prospective observational study[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2021, 12(3): 185. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.03.004 |

| [24] | Shojaee M, Safari S, Sabzghabaei A, et al. Pro-BNP versus MEDS score in determining the prognosis of sepsis patients; a diagnostic accuracy study[J]. Emerg (Tehran), 2018, 6(1): e4. |

| [25] | Scheer C, Fuchs C, Rehberg S. Biomarkers in severe sepsis and septic shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2016, 44(4): 849-850. DOI:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001507 |

| [26] | Kellum JA, Chawla LS, Keener C, et al. The effects of alternative resuscitation strategies on acute kidney injury in patients with septic shock[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016, 193(3): 281-287. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201505-0995OC |

| [27] | Houwink AP, Rijkenberg S, Bosman RJ, et al. The association between lactate, mean arterial pressure, central venous oxygen saturation and peripheral temperature and mortality in severe sepsis: a retrospective cohort analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2016, 20: 56. DOI:10.1186/s13054-016-1243-3 |

| [28] | Liu Z, Meng Z, Li Y, et al. Prognostic accuracy of the serum lactate level, the SOFA score and the qSOFA score for mortality among adults with sepsis[J]. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2019, 27(1): 51. DOI:10.1186/s13049-019-0609-3 |

| [29] | Shin J, Hwang SY, Jo IJ, et al. Prognostic value of the lactate/albumin ratio for predicting 28-day mortality in critically ILL sepsis patients[J]. Shock Augusta Ga, 2018, 50(5): 545-550. DOI:10.1097/SHK.0000000000001128 |

| [30] | Jensen JU, Heslet L, Jensen TH, et al. Procalcitonin increase in early identification of critically ill patients at high risk of mortality[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(10): 2596-2602. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000239116.01855.61 |

| [31] | Zhou J, Qian C, Zhao M, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in intensive care units in mainland China[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(9): e107181. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0107181 |

| [32] | Huang CT, Tsai YJ, Tsai PR, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in surgical intensive care units in northern Taiwan[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2015, 94(47): e2136. DOI:10.1097/md.0000000000002136 |

| [33] | Arabi Y, Al Shirawi N, Memish Z, et al. Assessment of six mortality prediction models in patients admitted with severe sepsis and septic shock to the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study[J]. Crit Care, 2003, 7(5): R116-R122. DOI:10.1186/cc2373 |

| [34] | Cheng B, Li Z, Wang J, et al. Comparison of the performance between sepsis-1 and sepsis-3 in ICUs in China: a retrospective multicenter study[J]. Shock, 2017, 48(3): 301-306. DOI:10.1097/shk.0000000000000868 |

| [35] | Khwannimit B, Bhurayanontachai R, Vattanavanit V. Comparison of the performance of SOFA, qSOFA and SIRS for predicting mortality and organ failure among sepsis patients admitted to the intensive care unit in a middle-income country[J]. J Crit Care, 2018, 44: 156-160. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.10.023 |

| [36] | Cabitza F, Rasoini R, Gensini GF. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine[J]. JAMA, 2017, 318(6): 517-518. DOI:10.1001/jama.2017.7797 |

| [37] | Zhang Z, Beck MW, Winkler DA, et al. Opening the black box of neural networks: methods for interpreting neural network models in clinical applications[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2018, 6(11): 216. DOI:10.21037/atm.2018.05.32 |

2021, Vol. 30

2021, Vol. 30