2 大连医科大学附属第一医院急诊科 116011

2 Emergency Department, First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116011, China

脓毒症是引起重症监护病房患者高病死率的主要原因之一[1-2]。贫血是脓毒症的常见并发症(超过60%),且可使病情复杂化[3-4]。引起脓毒症患者贫血的一个重要原因是铁代谢紊乱[3]。研究发现,脓毒症的铁代谢紊乱与炎症反应关系密切[5-8]。炎症因子白介素(interleukin-6,IL-6)可通过JAK2/STAT3信号通路调控肝脏对铁调素的合成[9-11], 其他炎症因子如IL-l、肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF-α)等也是先升高IL-6再作用于JAK2/STAT3[4]。铁调素是铁代谢的中心环节,脓毒症患者升高的铁调素可下调肠黏膜细胞和巨噬细胞膜铁转运蛋白的表达,并抑制肠道吸收铁和促进巨噬细胞内铁的储存,导致血浆铁下降,进而引起炎症相关性贫血[4]。迄今为止,针对炎症相关性贫血的治疗主要包括促红细胞生成素、铁螯合剂、铁调素拮抗剂和IL-6受体抗体等,但疗效均不确切[4]。乌司他丁是一种肝脏分泌的具有广谱蛋白酶抑制作用的内源性抑炎物质,可用于抑制脓毒症过度的炎症反应[12-14],但它对脓毒症患者铁代谢紊乱的影响尚未见报道。本文将探讨乌司他丁对脓毒症患者铁代谢及其对病情严重程度和预后的影响。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料收集2017年1月至2017年12月入住大连医科大学附属第一医院急诊ICU的脓毒症患者98例。纳入标准:符合“脓毒症3.0”的诊断标准[15]。

排除标准:(1)年龄 < 18岁;(2)既往有严重肝肾功能不全;(3)免疫性疾病及恶性肿瘤患者;(4)既往有贫血病史,或有外伤及其他显性失血(如消化道出血等)史;(5)接受输注血液制品治疗的患者;(6)接受激素治疗的患者;(7)住院期间放弃积极治疗的患者;(8)患者或亲属不同意纳入;(9)对乌司他丁过敏者;(10)资料不全者。

本研究方案被大连医科大学附属第一医院伦理委员会批准,并获患者或家属知情同意。

将纳入的脓毒症患者随机(随机数字法)分为常规治疗组(n=49)及乌司他丁组(n=49)。常规治疗组患者给予抗感染、补液及对症和支持等治疗;乌司他丁组患者在此基础上加用乌司他丁(天普生化医药有限公司,广东)20万U +生理盐水20 mL静脉注射,每日两次,连续用7~10 d。另外选取性别、年龄均匹配的健康志愿者为对照组(n=20)。

1.2 检测指标和方法记录所有纳入患者的性别、年龄、临床诊断、感染部位、所需的实验室检测结果等,并计算患者入院时的SOFA评分[15]。入院后第1天(健康志愿者为入组后)、第3天和第7天,抽取外周静脉血,离心(3 000 r/min, 15 min)后将血浆分装-80 ℃冻存备检。

采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA法)检测血浆铁蛋白(Abcam,英国)、促红细胞生成素(erythropoietin,EPO,Abcam,英国)、可溶性转铁蛋白受体(soluble transferrin receptor,sTFR,R & D,美国)、铁调素(优尔生公司,武汉)、白介素-6(IL-6,优尔生公司,武汉);血红蛋白和红细胞分布宽度由本院检验科全自动血细胞分析仪(XN-2000, Sysmex, 神户,日本)完成的血常规提供。

1.3 统计学方法应用SPSS 22.0进行统计分析。正态分布的计量资料用均数±标准差(Mean±SD)表示;不符合正态分布的计量资料用中位数(四分位数)表示。性别、感染部位及28 d病死率的组间比较采用Fisher精确概率法;正态分布的计量资料组间比较采用重复测量的方差分析检验,两两比较采用Bonferroni检验;非正态分布的计量资料组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis检验,两两比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。使用Kaplan-Meier法产生累积生存曲线,并采用log-rank法进行比较。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 基线数据的比较常规治疗组、乌司他丁组患者和对照组在年龄、性别和感染部位方面的差异均无统计学意义(均P > 0.05),见表 1。常规治疗组和乌司他丁组患者发病到入院的时间差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)

| 指标 | 对照组(n=20) | 常规治疗组(n=49) | 乌司他丁组(n=49) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄[岁, M(P25, P75)] | 65.6(49, 78) | 68.9(57, 82) | 68.7(56, 81) | 1.369 | 0.504 |

| 男性(例,%) | 12(60.0) | 32(65.3) | 29(59.2) | 0.471 | 0.848 |

| 发病到入院时间(d) | - | 3.04±1.32 | 3.37±1.39 | 0.461 | 0.646 |

| 感染部位(例,%) | |||||

| 肺部 | - | 31(63.3) | 28(57.1) | 0.379 | 0.538 |

| 腹腔 | - | 4(8.2) | 5(10.2) | 0.121 | 0.728 |

| 胆 | - | 9 (18.4) | 11(22.4) | 0.249 | 0.618 |

| 泌尿系统 | - | 2 (4.1) | 4(8.2) | 0.703 | 0.402 |

| 皮肤软组织 | - | 3(6.1) | 1(2.0) | 1.032 | 0.310 |

| 机械通气(例,%) | - | 36(73.5) | 38(77.6) | 0.163 | 0.686 |

| CRRT治疗(例,%) | - | 14(28.6) | 13(26.5) | 0.152 | 0.696 |

与对照组相比,常规治疗组患者入院后第1、3和7天的血红蛋白和血浆EPO及sTFR/log铁蛋白均显著降低(均P < 0.05,表 2),血浆sTFR、铁调素、铁蛋白和IL-6及红细胞分布宽度均显著升高(均P < 0.05);与常规治疗组相比,乌司他丁组患者入院后第3和7天的血浆EPO和sTFR/log铁蛋白均显著升高(均P < 0.05),而血浆铁调素、铁蛋白和IL-6均显著降低(均P < 0.05)。

| 指标 | 第1天 | 第3天 | 第7天 |

| 血红蛋白(g/L) | |||

| 对照组 | 135.5±3.5 | 135.6±3.6 | 136.1±3.1 |

| 常规治疗组 | 126.4±13.9a | 104.9±16.0a | 96.9±14.6a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 124.5±13.8 | 105.7±11.0 | 98.7±10.1 |

| 红细胞分布宽度(%) | |||

| 对照组 | 12.9±0.3 | 13.0±0.3 | 12.9±0.2 |

| 常规治疗组 | 13.2±1.2a | 14.1±1.0a | 14.6±1.1a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 13.3±1.4 | 14.4±1.3 | 14.5±1.2 |

| IL-6(pg/mL) | |||

| 对照组 | 5.3(3.8, 6.6) | 5.7(4.2, 6.9) | 5.6(3.9, 6.8) |

| 常规治疗组 | 85.7(36.9, 137.0)a | 51.6(24.1, 85.7)a | 37.8(23.4, 54.6)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 82.4(35.7, 127.0) | 36.4(17.8, 48.6)b | 23.8(18.9, 45.9)b |

| 铁调素(ng/mL) | |||

| 对照组 | 21.2(20.6, 22.0) | 22.0(21.1, 22.5) | 21.5(20.8, 22.2) |

| 常规治疗组 | 157.2(135.1, 180.5)a | 97.5(76.6, 103.5)a | 56.1(45.5, 68.2)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 147.7(126.9, 172.2) | 77.2(64.0, 95.2)b | 48.0(38.0, 57.3)b |

| 铁蛋白(ng/mL) | |||

| 对照组 | 30.3(29.9, 30.7) | 30.4(30.1, 31.1) | 30.6(29.9, 31.0) |

| 常规治疗组 | 205.4(173.9, 234.7)a | 582.9(554.7, 593.7)a | 314.8(293.6, 330.4)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 197.0(166.4, 225.5) | 549.5(505.9, 580.0)b | 290.8(224.2, 315.3)b |

| sTFR(nmol/L) | |||

| 对照组 | 15.1(14.5, 15.5) | 14.9(14.6, 15.6) | 15.1(14.7, 15.4) |

| 常规治疗组 | 20.6(16.9, 22.0)a | 19.5(16.8, 24.4)a | 22.8(19.8, 24.2)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 20.3(17.2, 24.1) | 20.9(17.8, 24.3) | 21.7(18.2, 23.4) |

| sTFR/log铁蛋白 | |||

| 对照组 | 10.2(9.8, 10.5) | 10.1(9.8, 10.5) | 10.1(9.9, 10.3) |

| 常规治疗组 | 9.0(7.5, 10.1)a | 8.8(7.4, 9.8)a | 8.9(.3, 10.9)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 9.1(7.4, 10.5) | 9.2(7.6, 9.9)b | 9.4(8.0, 10.1)b |

| EPO(U/L) | |||

| 对照组 | 11.2(10.5, 11.7) | 11.3(10.4, 11.6) | 11.3(10.5, 11.9) |

| 常规治疗组 | 73.0(44.9, 102.2)a | 28.3(21.4, 37.1)a | 15.7(10.8, 27.2)a |

| 乌司他丁组 | 75.4(52.3, 106.7) | 38.7(26.3, 57.7)b | 23.2(19.2, 29.7)b |

| 注:EPO,促红细胞生成素;sTFR,可溶性转铁蛋白受体;IL-6,白介素-6;与对照组比较,aP < 0.05;与常规治疗组比较,bP < 0.05;计量资料以M(P25, P75)表示 | |||

乌司他丁组与常规治疗组患者SOFA评分在入院第1天[(8.9±2.2)vs(8.6±2.3)]和第3天[(8.2±2.5)vs(8.4±2.7)]的差异无统计学意义(均P > 0.05)。乌司他丁组患者入院后第7天SOFA评分显著低于常规治疗组[(5.2±2.3)vs(6.4±2.7),P=0.019]。

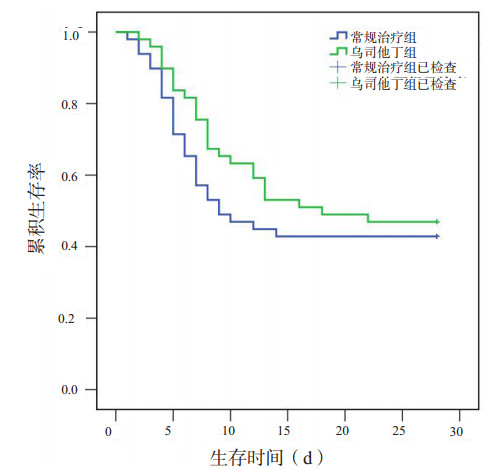

2.4 乌司他丁组与常规治疗组患者生存时间比较乌司他丁组和常规治疗组28 d存活率的差异无统计学意义(47% vs 43%,P=0.685)。Kaplan-Meier生存曲线显示,乌司他丁组患者的中位生存时间长于常规治疗组,但差异无统计学意义(18 d vs 9 d,P=0.363),见图 1。

|

| 图 1 两组患者的Kaplan-Meier生存曲线 Fig 1 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients in the Ulinastatin and conventional treatment groups |

|

|

本研究发现脓毒症患者早期血IL-6显著升高,且存在铁代谢紊乱,入院7 d后出现不同程度的贫血;乌司他丁可显著降低血IL-6水平并改善铁代谢紊乱和入院第7天的病情严重程度,有提高生存时间和降低患者28 d病死率的趋势,但差异未达到统计学意义,也不能改善脓毒症患者的贫血。

脓毒症是机体对感染的反应失调而导致危及生命的器官功能障碍[15]。脓毒症的炎症反应是一个复杂的网络,也与其他病理机制(包括铁代谢)相互影响。脓毒症患者显著升高的促炎介质IL-6可通过促进肝脏大量合成和分泌铁调素来影响铁代谢,而铁调素也可通过刺激巨噬细胞分泌大量的IL-6,进一步加重炎症反应[16]。本研究发现乌司他丁显著抑制脓毒症患者血IL-6和铁调素的升高,这可能与它的抑炎效应有关。笔者推测乌司他丁可能通过降低IL-6水平(抑炎效应)并通过IL-6/JAK2/STAT3信号通路间接地抑制铁调素的合成,进而影响其他铁代谢相关指标[17]。

铁蛋白是细胞内铁储存的一种主要形式,但铁蛋白又是一种急性期反应蛋白,炎症介质可诱导铁蛋白的合成[18]。故炎症状态下铁蛋白水平明显升高但不能作为炎症时铁储存的指标。sTFR不受炎症反应的影响,是判断炎症时机体是否缺铁的可靠生物标志物。sTFR/log铁蛋白的比值,也称铁蛋白指数,这个参数一方面考虑到对铁的需求,另一方面也考虑铁储存,因此比sTFR或铁蛋白单独使用时具有更高的诊断能力[19-20]。本研究发现脓毒症患者sTFR/log铁蛋白明显低于健康对照组,与以前的研究结果一致[21],但乌司他丁可显著升高sTFR/log铁蛋白的比值,这提示乌司他丁可能改善脓毒症患者对铁的利用度。

EPO是主要由肾脏产生的能刺激红细胞生成的激素,缺氧和贫血均促进EPO的产生[22],而促炎介质TNF-α和IL-6均可抑制EPO的产生[21, 23-24]。本研究发现脓毒症患者EPO浓度显著高于健康志愿者,提示影响脓毒症患者EPO产生的机制比较复杂,很可能促进EPO产生的刺激强于抑制其产生的刺激。本研究还发现乌司他丁组患者EPO浓度高于常规治疗组,这可能是乌司他丁的抑炎效应减轻了炎症介质对EPO产生的抑制,因而间接地促进EPO的产生。

红细胞分布宽度是反映红细胞大小形状一致程度的参数,用红细胞体积大小的变异系数来表示,为反映早期缺铁的指标。红细胞宽度大提示各种贫血、造血异常或者先天性红细胞异常[25]。一些研究发现红细胞分布宽度也与IL-6、CRP以及铁代谢紊乱相关[26-27]。本研究发现脓毒症患者红细胞分布宽度增加,可能是由于促炎介质抑制EPO诱导的红细胞成熟和增殖,并抑制骨髓红细胞前体的生成和下调EPO受体表达,降低铁的生物利用度等,使较新较大的网织红细胞进入循环导致红细胞分布宽度增加[28-31]。另外,炎症介质也促进红细胞凋亡和引起红细胞膜变形性的改变也可使红细胞分布宽度增加[31-33]。然而,本研究发现乌司他丁对红细胞分布宽度无明显影响,其原因尚不清楚。

本研究还发现脓毒症患者入院7 d后就出现明显贫血。然而,红细胞寿命约为120 d,若因铁调素升高引起低铁血症而致贫血,则约需要12 d机体内血红蛋白水平才降低10%[34]。故笔者认为脓毒症时骨髓造血功能的抑制,巨噬细胞对红细胞的破坏增加及铁调素对红细胞生成的直接抑制等综合因素使患者入院约7 d后即贫血。同时乌司他丁组与常规治疗组血红蛋白之间差异无统计学意义,提示虽然乌司他丁可改善脓毒症患者的铁代谢紊乱,但并不改善贫血,其原因尚不清楚,很可能与本研究观察时间较短有关,故乌司他丁能否改善脓毒症患者的贫血还需进一步研究。

综上所述,脓毒症患者早期存在铁代谢紊乱和炎症性贫血;乌司他丁有可能改善脓毒症患者铁代谢紊乱和病情严重程度,但不能显著患者改善的贫血和预后。但由于本研究病例数偏少,尚需继续扩大样本量,以进一步明确乌司他丁对患者生存时间和28 d病死率的影响。

| [1] | Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts[J]. JAMA, 2014, 312(1): 90-92. DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.5804 |

| [2] | 何新华, 陈云霞, 李春盛. 论重症感染[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2015, 24(4): 349-351. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2015.04.001 |

| [3] | Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, et al. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients[J]. JAMA, 2002, 288(12): 1499-1507. DOI:10.1001/jama.288.12.1499 |

| [4] | 姜毅, 龚平. 铁代谢紊乱与脓毒症[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(2): 229-232. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.02.027 |

| [5] | Ganz T. Systemic iron homeostasis[J]. Physiol Rev, 2013, 93(4): 1721-1741. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00008.2013 |

| [6] | Soares MP, Hamza I. Macrophages and iron metabolism[J]. Immunity, 2016, 44(3): 492-504. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.016 |

| [7] | Patteril MV, Davey-Quinn AP, Gedney JA, et al. Functional iron deficiency, infection and systemic inflammatory response syndrome in critical illness[J]. Anaesth Intensive Care, 2001, 29(5): 473-478. |

| [8] | Eckardt KU. Anaemia of critical illness——implications for understanding and treating rHuEPO resistance[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2002, 17(5): 48-55. DOI:10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_5.48 |

| [9] | Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis[J]. Science, 2012, 338(6108): 768-772. DOI:10.1126/science.1224577 |

| [10] | Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3[J]. Blood, 2006, 108(9): 3204-3209. DOI:10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631 |

| [11] | Pietrangelo A, Dierssen U, Valli L, et al. STAT3 is required for IL-6-gp130-dependent activation of hepcidin in vivo[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 132(1): 294-300. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.018 |

| [12] | 李文华, 宋志芳, 单慧敏. 乌司他丁对脓毒症大鼠肺损伤的保护作用[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2007, 16(2): 132-137. DOI:10.3760/j.issn.1671-0282.2007.02.005 |

| [13] | 尹海燕, 陶珮, 叶小玲, 等. 乌司他丁对老年脓毒症患者肠屏障功能的保护作用[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2016, 25(2): 177-181. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2016.02.008 |

| [14] | 陈俊杰, 李青松, 李永宁, 等. 乌司他丁抑制脓毒症大鼠心肌细胞凋亡及Caspase-3信号机制研究[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2018, 27(1): 72-77. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.01.015 |

| [15] | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [16] | Hugman A. Hepcidin:an important new regulator of iron homeostasis[J]. Clin Lab Haematol, 2006, 28(2): 75-83. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00768.x |

| [17] | Kemna E, Pickkers P, Nemeth E, et al. Time-course analysis of hepcidin, serum iron, and plasma cytokine levels in humans injected with LPS[J]. Blood, 2005, 106(5): 1864-1866. DOI:10.1182/blood-2005-03-1159 |

| [18] | Branco RG, Garcia PC. Ferritin and C-reactive protein as markers of systemic inflammation in sepsis[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2017, 18(2): 194-196. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001036 |

| [19] | Suominen P, Punnonen K, Rajamaki A, et al. Serum transferrin receptor and transferrin receptor-ferritin index identify healthy subjects with subclinical iron deficits[J]. Blood, 1998, 92(8): 2934-2939. |

| [20] | Suominen P, Möttönen T, Rajamäki A, et al. Single values of serum transferrin receptor and transferrin receptor ferritin index can be used to detect true and functional iron deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis patients with anemia[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2000, 43(5): 1016-1020. DOI:10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1016::AID-ANR9>3.0.CO;2-3 |

| [21] | Angeles Vazquez Lopez M, Molinos FL, Carmona ML, et al. Serum transferrin receptor in children:usefulness for determinating the nature of anemia in infection[J]. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 2006, 28(12): 809-815. DOI:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31802d751a |

| [22] | Jelkmann W, Hellwig-Burgel T. Biology of erythropoietin[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2001, 502: 169-187. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4757-3401-0 |

| [23] | Johnson CS, Cook CA, Furmanski P. In vivo suppression of erythropoiesis by tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha):reversal with exogenous erythropoietin (EPO)[J]. Exp Hematol, 1990, 18(2): 109-113. |

| [24] | Jongen-Lavrencic M, Peeters HR, Rozemuller H, et al. IL-6-induced anaemia in rats:possible pathogenetic implications for anaemia observed in chronic inflammations[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 1996, 103(2): 328-334. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-622.x |

| [25] | Bazick HS, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, et al. Red cell distribution width and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care Med, 2011, 39(8): 1913-1921. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b85c6 |

| [26] | Allen LA, Felker GM, Mehra MR, et al. Validation and potential mechanisms of red cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in heart failure[J]. J Card Fail, 2010, 16(3): 230-238. DOI:10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.11.003 |

| [27] | Perlstein TS, Weuve J, Pfeffer MA, et al. Red blood cell distribution width and mortality risk in a community-based prospective cohort[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2009, 169(6): 588-594. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.55 |

| [28] | Ghali JK. Anemia and heart failure[J]. Curr Opin Cardiol, 2009, 24(2): 172-178. DOI:10.1097/HCO.0b013e328324ecec |

| [29] | Laftah AH, Sharma N, Brookes MJ, et al. Tumour necrosis factor α causes hypoferraemia and reduced intestinal iron absorption in mice[J]. Biochem J, 2006, 397(1): 61-67. DOI:10.1042/BJ20060215 |

| [30] | Scharte M, Fink MP. Red blood cell physiology in critical illness[J]. Crit Care Med, 2003, 31(12 Suppl): S651-657. DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000098036.90796.ED |

| [31] | Pierce CN, Larson DF. Inflammatory cytokine inhibition of erythropoiesis in patients implanted with a mechanical circulatory assist device[J]. Perfusion, 2005, 20(2): 83-90. DOI:10.1191/0267659105pf793oa |

| [32] | Chiari MM, Bagnoli R, de Luca P, et al. Influence of acute inflammation on iron and nutritional status indexes in older inpatients[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1995, 43(7): 767-771. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07047.x |

| [33] | Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352(10): 1011-1023. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra041809 |

| [34] | van Eijk LT, Kroot JJ, Tromp M, et al. Inflammation-induced hepcidin-25 is associated with the development of anemia in septic patients:an observational study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(1): R9. DOI:10.1186/cc9408 |

2019, Vol. 28

2019, Vol. 28