2. 苏州大学附属第二医院急重症医学科,苏州 215004;

3. 苏州大学附属太仓医院(太仓市第一人民医院)重症医学科,太仓 215400

2. Intensive Care Unit, Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215004, China;

3. Intensive Care Unit, Taicang Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University (First People's Hospital of Taicang), Taicang 215400, China

创伤后纤维蛋白溶解失调是创伤性凝血病的主要机制之一[1]。在CRASH-2研究进一步表明创伤后大出血获益于氨甲环酸(Tranexamic acid, TXA)治疗后[2],抗纤溶已成为创伤大出血患者的重要治疗手段。《创伤后大出血与凝血病管理的欧洲指南》推荐尽早使用TXA,且无需等待血栓弹力图(thromboelastography, TEG)测定的纤溶结果[3]。TEG测定的纤溶状态可分为三种表型,即纤维蛋白溶解关闭(fibrinolysis shutdown, SD)、生理性纤维蛋白溶解(physiologic fibrinolysis, PY)以及纤维蛋白溶解亢进(hyperfibrinolysis, HF)[4]。研究表明,SD患者易发生静脉血栓和脏器功能不全,而HF患者出血风险高[4-5];并且纤溶状态随着病程发生变化,表现为急性纤溶关闭、持续性纤溶关闭,以及获得性纤溶抵抗等状态[6]。由于上述病理状态具有不同的发生、发展规律,且与临床预后相关,提示可能需要不同的治疗策略[5, 7]。鉴于严重创伤患者抗纤溶治疗后的纤溶状态变化及其影响因素研究较少;故此,本研究利用TEG动态检测严重创伤患者初期纤溶状态,以及经初期复苏后纤溶的变化趋势,试图探明纤溶状态的变化规律及其与临床预后的关系。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为前瞻性队列研究,将2021年7月至2022年12月期间,在苏州大学附属太仓医院创伤中心救治并符合以下入选标准者纳入研究。入选标准[3]:(1)严重创伤患者,即创伤严重程度评分(Injury Severe Score, ISS)≥16分;(2)入急诊时收缩压 < 90 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa),或格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow Coma Scale, GCS)≤8分,或由经治医生认定存在大出血风险者。排除标准[3, 8]:(1)既往有凝血功能异常或长期口服抗凝或抗血小板药物者;(2)有酗酒、恶性肿瘤、脏器功能障碍,或静脉血栓栓塞症等病史;(3)已存在弥散性血管内凝血等使用抗纤溶药物禁忌证者;(4)脑疝且双瞳散大;(5)受伤时间 > 3 h;(6)烧伤;(7)院前心脏骤停;(8)年龄 < 18周岁;(9)未签署知情同意书。

根据患者测定的血块溶解速率(clot lysis at 30 min, LY30)值,将其分成三种表型[4, 9-10]:(1)SD,即LY30 < 0.8%;(2)PY,即0.8%≤LY30 < 3.0%;(3)HF,即LY30≥3.0%。本研究根据患者进入抢救室首次测定的纤溶表型,分成SD、PY以及HF三组。

本研究患者家属或法定代理人签署伦理知情同意书,经太仓市第一人民医院医学伦理委员会批准(伦理号:KY-2020-214)。研究方案在中国临床试验注册中心注册(注册号:ChiCTR2300078089)。

1.2 救治流程抢救流程:创伤患者进入创伤中心(苏州市级),立即启动创伤治疗小组,按创伤高级生命支持流程(ABCDE)依次评估患者气道和颈椎(A),必要时建立人工气道和固定颈椎;评估呼吸状态,必要时氧疗甚至机械通气(B);评估循环状态,给予循环支持,包括可压迫部位的止血、使用抗纤治疗(详见下述)、输注晶体液和血制品,采取允许性低血压复苏策略(C);评估神经系统(D);暴露全身和保温(E)[11]。在上述评估和治疗后,当收缩压≥90 mmHg,经皮脉氧饱和度(SpO2)≥90%时,尽快完成全身计算机断层扫描(computed tomography, CT)等检查,以明确致命性损伤以及是否需要手术或介入治疗。

抗纤溶治疗:满足纳排标准的患者立即在10 min内静脉输入1 g TXA(中国湖南赛隆药业有限公司生产),后续8 h静脉输注1 g[3];当TEG检测发现LY30 < 3.0%时,停用TXA。

1.3 观察指标基线资料:患者的性别、年龄、受伤机制及受伤至急诊时间,入院时体温、血压、心率、GCS、血红蛋白、红细胞压积、血小板计数、血乳酸、凝血酶原时间(prothrombin time, PT)、活化部分凝血酶原时间(activated partial thromboplastin time, APTT)、纤维蛋白原、纤维蛋白原降解产物、凝块反应时间(reaction time, R)、凝块形成时间(kinetic time, K)、α角、血栓最大振幅(maximum amplitude, MA)、LY30以及ISS等基线资料。

纤溶指标:入复苏单元时(0 h)、初期复苏后1 h及8 h分别检测TEG。TEG样本采集后,将试管颠倒3~6次以充分混匀后保持样本直立,采血至检测时间 < 1 h。样本由每班固定的急诊专科护士负责检测,检测采用YZ5000型血栓弹力图仪(中国陕西裕泽毅医疗科技有限公司生产,软件版本YZ V4.0.0)。

主要预后指标:患者24 h和28 d全因病死率。

次要预后指标:患者24 h输液量、24 h输血量、大量输血发生率、机械通气天数、重症医学科(intensive care unit, ICU)住院天数、总住院天数、下肢深静脉血栓形成(deep venous thrombosis, DVT)的发生率,以及多器官功能障碍综合征(multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, MODS)发生率等。

1.4 相关定义(1) 大出血:24 h内失血量达到或超过全身血容量,或3 h内失血量达到全身血容量的50%[12]。(2)大量输血:成人患者24 h内输注红细胞悬液≥18 U(1 U红细胞悬液由200 mL全血制备),或输注红细胞悬液≥0.3 U/kg[13]。(3)MODS:根据序贯器官衰竭评分(sequential organ failure assessment, SOFA)判定患者是否存在MODS,每天记录患者各项指标,并根据每日最差值来评价器官功能状态,当有两个或两个以上的器官≥3分时诊断MODS[14]。

1.5 统计学方法应用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计分析。所有连续变量采用正态性检验,正态分布计量资料用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,两组间比较采用t检验,多组间比较采用F检验;非正态分布计量资料用中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1, Q3)]表示,两组间比较采用Mann Whitney U检验,多组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis检验。采用Bonferroni法进行校正。计数资料以百分数表示,两组、多组间率比较采用χ2检验或Fisher精确检验。

采用单因素分析非纤溶亢进患者28 d死亡的风险因素,用差异有统计学意义的变量建立二元多因素Logistic回归模型,分析初期复苏后纤溶状态变化与患者28 d死亡风险的关系。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

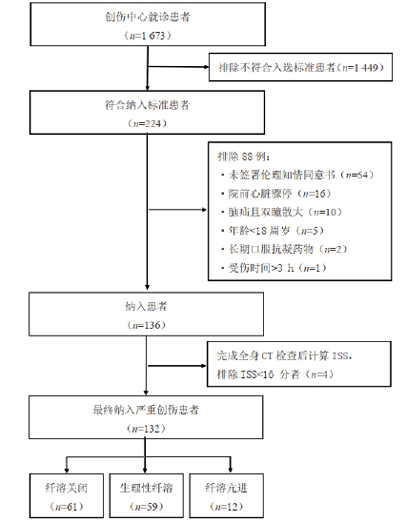

2 结果 2.1 患者的基线资料研究期间共诊治1 673例创伤患者,符合纳入标准224例,排除88例后共136例接受TXA抗纤溶治疗,完成全身CT检查后计算ISS,排除ISS < 16分患者4例,最终132例患者进入分析(见图 1),其中男92例,女40例,年龄为58(45, 67)岁,受伤至急诊时间为60(49, 60)min,ISS为29(25, 34)分。SD组患者昏迷和头部简明损伤定级(abbreviated injury scale, AIS)≥3比率最高,且与其他两组差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05);HF组患者心率、PT、APTT、R和K值最高,α角和MA值最低,且与其他两组差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)。三组患者间,PY组患者腹部AIS≥3比率最高,其次为HF组,SD组最低(P < 0.05);HF组患者四肢骨盆AIS≥3比率、低血压发生率、乳酸值最高,其次为PY组,SD组最低,三组间差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)。见表 1。

|

| 图 1 患者筛选流程图 Fig 1 Patient screening flowchart |

|

|

| 指标 | 总体(n=132) | SD组(n=61) | PY组(n=59) | HF组(n=12) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 58(45, 67) | 59(51, 68) | 51(38, 67) | 61(53, 69) | 5.822 | 0.054 |

| 男/女 | 92/40 | 41/20 | 43/16 | 8/4 | 0.514 | 0.774 |

| 受伤至急诊时间(min)a | 60(49, 60) | 60(60, 85) | 60(30, 60) | 60(51, 60) | 3.634 | 0.162 |

| 致伤机制(例,%) | ||||||

| 交通伤 | 89(67.4) | 46(75.4) | 35(59.3) | 8(66.7) | ||

| 高处坠落伤 | 32(24.2) | 12(19.7) | 17(28.8) | 3(25.0) | 4.084 | 0.367 |

| 其他 | 11(8.3) | 3(4.9) | 7(11.9) | 1(8.3) | ||

| 体温(℃)b | 36.4±0.6 | 36.4±0.6 | 36.3±0.7 | 36.3±0.7 | 0.255 | 0.775 |

| HR(次/min)a | 86(72, 107) | 84(70, 106)d | 86(72, 102)d | 106(87, 116) | 6.225 | 0.044 |

| SBP < 90 mmHg(例,%) | 51(38.6) | 10(16.4)cd | 29(49.2)d | 12(100.0) | 34.54 | < 0.001 |

| GCS≤8分(例,%) | 83(62.9) | 52(85.2)cd | 25(42.4) | 6(50.0) | 24.56 | < 0.001 |

| Hb(g/L)b | 129.8±19.8 | 133.0±17.3d | 129.4±20.5 | 115.4±23.1 | 4.173 | 0.018 |

| HCTb | 38.9±5.5 | 39.7±4.7d | 38.8±5.8 | 35.3±6.9 | 3.432 | 0.035 |

| PLT(×109/L)a | 216(179, 256) | 222(175, 255) | 216(197, 256) | 136(108, 291) | 2.489 | 0.288 |

| Lac(mmol/L)a | 2.1(1.3, 3.9) | 1.5(1.2, 2.8)cd | 2.5(1.5, 4.2)d | 4.9(3.5, 5.3) | 21.920 | < 0.001 |

| PT(s)a | 12.2(11.5, 12.9) | 12.1(11.3, 12.6)d | 12.0(11.5, 13.1)d | 13.1(12.4, 14.3) | 10.138 | 0.006 |

| APTT(s)a | 24.4(22.9, 26.4) | 24.1(23.0, 26.4)d | 24.2(22.7, 26.1)d | 26.7(24.7, 30.0) | 7.165 | 0.028 |

| Fib(g/L)a | 2.1(1.9, 2.4) | 2.2(2.0, 2.5) | 2.1(1.9, 2.4) | 2.0(1.1, 2.3) | 4.525 | 0.104 |

| FDP(mg/L)a | 78.2(24.6, 178.5) | 92.0(25.2, 170.0) | 50.1(23.9, 172.7) | 144.9(50.1, 389.9) | 3.367 | 0.186 |

| R(min)b | 4.7±0.8 | 4.7±0.7d | 4.5±0.6d | 5.7±1.3 | 27.844 | 0.006 |

| K(min)a | 1.9(1.6, 2.3) | 1.9(1.7, 2.2)d | 1.8(1.5, 2.3)d | 3.0(2.4, 3.7) | 16.110 | < 0.001 |

| α角(°)b | 62.1±6.5 | 62.4±6.3d | 63.5±5.4d | 53.7±6.4 | 13.973 | < 0.001 |

| MA(mm)b | 61.3±6.0 | 62.8±5.3d | 61.5±4.7d | 52.0±7.5 | 21.149 | < 0.001 |

| LY30(%)a | 1.05(0.10, 1.80) | 0.10(0.10, 0.25)cd | 1.60(1.20, 2.10)d | 7.00(6.23, 16.50) | 107.485 | < 0.001 |

| AIS头≥3(例,%) | 97(73.5) | 54(88.5)cd | 37(62.7) | 6(50.0) | 13.992 | 0.001 |

| AIS胸≥3(例,%) | 45(34.1) | 15(24.6) | 25(42.4) | 5(41.7) | 4.558 | 0.102 |

| AIS腹≥3(例,%) | 31(23.5) | 7(11.5)cd | 22(37.3)d | 2(16.7) | 11.462 | 0.003 |

| AIS四肢≥3(例,%) | 40(30.3) | 13(21.3)cd | 20(33.9)d | 7(58.3) | 7.160 | 0.028 |

| ISSa | 29(25, 34) | 26(25, 33) | 29(25, 34) | 33(21, 42) | 1.554 | 0.460 |

| 注:HR为心率,SBP为收缩压,GCS为格拉斯哥昏迷评分,Hb为血红蛋白,HCT为红细胞压积,PLT为血小板计数,Lac为血乳酸,PT为凝血酶原时间,APTT为活化部分凝血酶原时间,Fib为纤维蛋白原,FDP为纤维蛋白原降解产物,R为凝块反应时间,K为凝块形成时间,α角为凝固角,MA为血栓最大振幅,LY30为血块溶解速率,AIS为简明损伤定级,ISS为损伤严重度评分,SD为纤溶关闭,PY为生理性纤溶,HF为纤溶亢进;a为M(Q1, Q3),b为x ± s;与PY组比较,cP < 0.05,与HF组比较,dP < 0.05 | ||||||

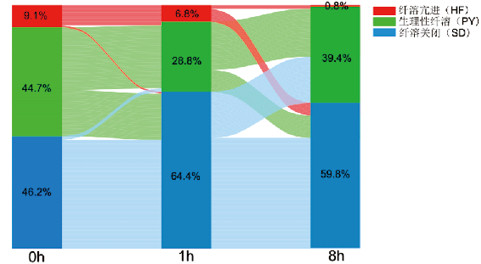

所有患者入复苏单元时的纤溶状态以SD表型(61例,46.2%)、PY表型(59例,44.7%)为主,HF表型(12例,9.1%)占比最低。

SD在初期复苏后1 h增多,主要是由PY转变而来;至8 h,部分SD转变为PY,亦有部分PY和HF向SD转变,最终表现为SD稍有减少。HF在复苏后1 h稍有减少,分别向SD、PY转变;至8 h,仅1例(0.8%)仍处于HF,其余均转变为SD,未有其他表型向HF转变。

初期复苏后8 h,SD仍为主要的纤溶表型(79例,59.8%),PY次之(52例,39.4%),HF最少(1例,0.8%)。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 初期复苏后纤溶状态的动态变化 Fig 2 Dynamic Changes in Fibrinolysis Status After Initial Resuscitation |

|

|

主要预后指标:与SD、PY组患者相比,HF组24 h病死率(25.0% vs. 3.3% vs. 3.4%,P < 0.05)和28 d病死率(58.3% vs. 32.8% vs. 11.9%,P < 0.05)最高,以大出血(4例,57.1%)为主要死亡原因,差异具有统计学意义。与PY组患者相比,SD组28 d病死率(32.8% vs. 11.9%,P < 0.05)较高,以脑外伤(15例,75.0%)为主要死亡原因,差异有统计学意义。见表 2。

| 指标 | 总体(n=132) | SD组(n=61) | PY组(n=59) | HF组(n=12) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 急诊手术(例,%) | 96(72.7) | 48(78.7) | 39(66.1) | 9(75.0) | 2.430 | 0.297 |

| 手术时间(min)a | 105(73, 150) | 100(71, 139) | 120(75, 171) | 120(75, 165) | 1.158 | 0.560 |

| 24 h输注晶体液(L)a | 5.0(3.7, 6.8) | 4.8(3.5, 6.7)c | 4.7(3.7, 6.7)c | 6.8(5.2, 10.1) | 6.069 | 0.048 |

| 24 h输注血浆(mL)a | 400(400, 1 000) | 400(400, 900)c | 400(400, 800)c | 1 800(1 000, 2 900) | 18.218 | < 0.001 |

| 24 h输注冷沉淀(U)a | 0.0(0.0, 0.0) | 0.0(0.0, 0.0) | 0.0(0.0, 0.0) | 0.0(0.0, 3.8) | 5.807 | 0.054 |

| 24 h输注红细胞(U)a | 3(2, 7) | 3(2, 6)c | 3(2, 6)c | 13(8, 16) | 18.378 | < 0.001 |

| 24 h输注血小板(U)a | 0.0(0.0, 0.0) | 0.0(0.0, 0.0)c | 0.0(0.0, 0.0) | 0.0(0.0, 3.8) | 6.193 | 0.045 |

| 大量输血(例,%) | 19(14.4) | 6(9.8)c | 5(8.5)c | 5(41.6) | 10.870 | 0.004 |

| 机械通气天数(d)a | 3(1, 6) | 4(2, 7)bc | 1(0, 4) | 1(0, 3) | 13.414 | 0.001 |

| ICU住院天数(d)a | 8(4, 13) | 8(5, 14)c | 8(4, 13)c | 3(1, 5) | 9.39 | 0.009 |

| 总住院天数(d)a | 24(12, 34) | 26(7, 34)c | 25(17, 36)c | 4(1, 18) | 11.341 | 0.003 |

| DVT(例,%) | 31(23.5) | 16(26.2) | 14(23.7) | 1(8.3) | 1.791 | 0.408 |

| MODS(例,%) | 28(21.2) | 14(23.0)bc | 8(13.6)c | 6(50.0) | 8.128 | 0.017 |

| 24 h死亡(例,%) | 7(5.3) | 2(3.3)c | 2(3.4)c | 3(25.0) | 6.801 | 0.040 |

| 28 d死亡(例,%) | 34(25.8) | 20(32.8)b | 7(11.9)c | 7(58.3) | 14.190 | 0.001 |

| 死亡原因(例,%) | 9.472 | 0.027 | ||||

| 大出血 | 5(14.7) | 1(5.0)bc | 0(0.0)c | 4(57.1) | ||

| 脑外伤 | 22(64.7) | 15(75.0) | 5(71.4) | 2(28.6) | ||

| MODS | 7(20.6) | 4(20.0) | 2(28.6) | 1(14.3) | ||

| 注:DVT为下肢深静脉血栓形成,MODS为多器官功能障碍综合征,SD为纤溶关闭,PY为生理性纤溶,HF为纤溶亢进;a为M(Q1, Q3);与PY组比较,bP < 0.05;与HF组比较,cP < 0.05 | ||||||

次要预后指标:与SD、PY组患者相比,HF组24 h晶体液输注量、血浆输注量、悬浮红细胞输注量高、大量输血,以及MODS发生率最高;ICU住院天数和总住院天数少,差异均有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)。与PY、HF组比较,SD组机械通气天数最高,差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05);三组间DVT发生率差异无统计学意义。见表 2。

2.4 非纤溶亢进患者初期复苏后纤溶状态变化与预后的关系除12例HF患者外,纳入的120例患者均只给予TXA负荷剂量,其中28 d死亡患者27例(22.5%)。根据患者28 d是否死亡分组进行单因素分析,提示年龄、GCS≤8分、PT、α角、24 h晶体液输注量和初期复苏后纤溶状态变化指标组间差异有统计学差异(表 3)。将上述变量纳入二元多因素Logistic回归分析,结果发现,在校正了年龄、GCS≤8分、PT及24 h晶体液输注量后,与持续生理性纤溶状态相比,初期复苏后处于持续纤溶关闭状态是严重创伤患者28 d死亡的危险因素(OR=7.009,95%CI: 1.141~43.079,P=0.036)(见表 4)。

| 变量 | 28d是否死亡 | 统计值 | P值 | ||

| 否(93例,77.5%) | 是(27例,22.5%) | ||||

| 年龄(岁)a | 53±15 | 61±10 | -2.823 | 0.006 | |

| 男/女 | 65/28 | 19/8 | 0.002 | 0.962 | |

| 致伤时间(min)b | 60(60, 60) | 60(30, 90) | -0.911 | 0.362 | |

| 受伤机制(例,%) | 4.372 | 0.112 | |||

| 交通伤 | 59(63.4) | 22(81.5) | |||

| 坠落伤 | 24(25.8) | 5(18.5) | |||

| 其他 | 10(10.8) | 0 | |||

| HR(次/min)a | 87±19 | 93±28 | -1.037 | 0.307 | |

| SBP < 90(例,%) | 32(34.4) | 7(25.9) | 0.686 | 0.407 | |

| GCS≤8(例,%) | 54(58.1) | 23(85.2) | 6.694 | 0.010 | |

| Hb(g/L)a | 131.1±19.5 | 131.6±17.2 | -0.111 | 0.912 | |

| HCT a | 39.3±5.4 | 39.1±4.8 | 0.192 | 0.848 | |

| PLT(×109/L)b | 222(192, 262) | 210(178, 243) | -0.93 | 0.352 | |

| Lac(mmol/L)b | 2.1(1.4, 3.6) | 1.5(1.0, 4.4) | -1.013 | 0.311 | |

| PT(s)b | 11.9(11.4, 12.7) | 12.3(11.8, 12.9) | -1.988 | 0.047 | |

| APTT(s)b | 24.1(22.8, 26.0) | 25.1(23.0, 26.5) | -1.326 | 0.185 | |

| Fib(g/L)b | 2.2(1.9, 2.4) | 2.1(1.8, 2.5) | -0.871 | 0.384 | |

| FDP(mg/L)b | 56.3(24.0, 166.5) | 113.0(24.6, 194.9) | -0.877 | 0.381 | |

| R(min)a | 4.5±0.6 | 4.8±0.7 | -1.928 | 0.056 | |

| α角(°)b | 65.2(59.6, 67.5) | 58.3(55.4, 66.5) | -2.379 | 0.017 | |

| MA(mm)a | 62.6±4.9 | 60.9±5.5 | 1.556 | 0.122 | |

| 胸部AIS≥3(例,%) | 34(36.6) | 6(22.2) | 1.935 | 0.164 | |

| 腹部AIS≥3(例,%) | 25(26.9) | 4(14.8) | 1.663 | 0.197 | |

| 四肢AIS≥3(例,%) | 28(30.1) | 5(18.5) | 1.41 | 0.235 | |

| ISS(分)b | 29(25, 33) | 30(25, 35) | -1.702 | 0.089 | |

| 24 h晶体液输注量(L)b | 4.6(3.5, 6.0) | 6.8(4.1, 8.5) | -2.816 | 0.005 | |

| 初期复苏后纤溶状态变化(例,%) | 11.040 | 0.010 | |||

| PY-PY | 35(37.6) | 3(11.1)a | |||

| PY-SD | 17(18.3) | 4(14.8) | |||

| SD-PY | 11(11.8) | 2(7.4) | |||

| SD-SD | 30(32.3) | 18(66.7)a | |||

| 注:HR为心率,SBP为收缩压,GCS为格拉斯哥昏迷评分,Hb为血红蛋白,HCT为红细胞压积,PLT为血小板计数,Lac为血乳酸,PT为凝血酶原时间,APTT为活化部分凝血酶原时间,Fib为纤维蛋白原,FDP为纤维蛋白原降解产物,R为凝块反应时间,α角为凝固角,MA为血栓最大振幅,AIS为简明损伤定级,ISS为损伤严重度评分,PY为生理性纤溶,SD为纤溶关闭;a为x ± s,b为M(Q1, Q3);与非28 d死亡组比较,cP < 0.05 | |||||

| 指标 | B | S.E. | Wald | P值 | OR | 95%CI |

| 年龄 | 0.048 | 0.023 | 4.391 | 0.036 | 1.049 | 1.003~1.097 |

| GCS≤8分 | 2.194 | 0.91 | 5.807 | 0.016 | 8.969 | 1.506~53.412 |

| PT | 0.906 | 0.347 | 6.819 | 0.009 | 2.474 | 1.253~4.881 |

| α角 | -0.029 | 0.047 | 0.380 | 0.538 | 0.971 | 0.886~1.065 |

| 24 h晶体液输注量 | 0.512 | 0.14 | 13.396 | < 0.001 | 1.668 | 1.268~2.193 |

| 初期复苏后纤溶状态变化 | ||||||

| PY-PY | 5.331 | 0.149 | 1.000(基准组) | |||

| PY-SD | 1.943 | 1.051 | 3.418 | 0.064 | 6.977 | 0.890~54.709 |

| SD-PY | 0.963 | 1.195 | 0.649 | 0.420 | 2.620 | 0.252~27.258 |

| SD-SD | 1.947 | 0.926 | 4.418 | 0.036 | 7.009 | 1.141~43.079 |

| 注:GCS为格拉斯哥昏迷评分,PT为凝血酶原时间,α角为凝固角,SD为纤溶关闭,PY为生理性纤溶,HF为纤溶亢进 | ||||||

本研究利用TEG检测不同时间点的纤溶状态,动态观察了严重创伤后不同纤溶表型的发生及其经抗纤溶等治疗后的变化。结果表明,严重创伤患者早期及抗纤溶等初期复苏后以SD、PY为主,SD较PY患者病死率高,初期复苏后处于持续SD状态增加了严重创伤患者28d死亡的风险。

3.1 纤溶状态的分布及变化本研究中严重创伤患者入院时SD、PY和HF的发生率依次为46.2%(61例)、44.7%(59例)和9.1%(12例),与以往3项关于严重创伤研究所示的纤溶分布相似[4, 15-16]。

本研究显示,HF组中严重骨盆、躯干外伤合并休克者居多,其发生可能与低灌注后内皮细胞损伤导致的组织型纤溶酶原激活物(tissue-type plasminogen activator, t-PA)释放增加有关[17];且早期凝血功能更差,大量输血发生率(41.6%)和病死率(58.3%)更高;83.3%(10例)HF表型经早期复苏后8 h转变为SD表型。Moore等[18]发现多数HF患者在创伤后数小时转变为SD,甚至在12 h后仍以SD为主,这种转变不仅受纤溶抑制剂影响,还与有效复苏密切相关。HF会随着纤溶抑制剂减少、血小板功能障碍而进展,而有效复苏可缓解33%的HF,因复苏后肝脏除了自身清除t-PA外,还可产生纤溶酶原激活物抑制剂1(plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, PAI-1)从而抑制纤溶[18]。

本研究中入院时SD发生率为46.2%,检测时间为创伤后60(60, 85)min,多见于重型脑外伤患者(52例,85.2%)。既往研究显示TEG测定的SD发生率在38%~64%[16, 19-20],与本研究相近。既往研究发现,SD的发生在创伤后随时间而增加,创伤现场检测SD发生率为22%[21],伤后2 h检测为58%[22],伤后12 h则增加到65%[4]。SD为中重度脑外伤患者最常见的表型[23-24],这可能与血脑屏障破坏后组织因子大量释放入血后激活外源性凝血途径相关[25]。

3.2 纤溶状态变化对临床预后的影响本研究的结果表明,在排除HF患者后,年龄、GCS评分、入院时凝血状态(PT和α角)、24 h晶体液输注量,以及纤溶状态变化与临床预后关系密切,其中GCS分级仍然是重要的预后影响因素(OR=8.969,95%CI: 1.506~53.412,P=0.016);进一步分析发现,在校正了年龄、GCS≤8分、PT以及24 h晶体液输注量后,严重创伤经抗纤溶等初期复苏后处于持续SD状态的患者,其28 d病死率较患者增加6倍。多中心前瞻性研究发现,创伤24 h后仍处于SD的患者病死率增加2倍[26];而与从纤溶关闭中恢复的患者相比,创伤7 d后仍维持SD的患者病死率增加7倍[7]。持续SD可能与PAI-1持续升高密切相关。对SD患者的研究表明,在纤溶激活7 h后PAI-1和tPA复合物增加了200倍,而在21 h后PAI-1水平仍然增加近100倍[27];其次,TXA也可能是促使持续SD的原因之一,但它的使用与SD的关系尚未明确。回顾性研究发现,TXA是SD发生的危险因素(OR=1.35,95%CI: 1.10~1.64)[15];但针对700例颅脑外伤患者的研究并未发现TXA会增加SD发生率[28]。另有研究发现,TXA会促使纤溶向SD转变,但其对不同纤溶转变患者的预后并无影响[5]。

本研究结果提示,在严重创伤早期利用TEG动态检测患者的纤溶状态,评估早期纤溶状态的变化;其次,创伤后纤溶呈动态变化,且受多种因素的影响,不应仅关注入院时的纤溶表型确定患者的纤溶状态。

3.3 本研究的局限性首先此研究为观察性队列研究,且Logistic回归分析中死亡病例样本量较少,可能对结果产生影响;其次此研究仅以TEG评估纤溶,没有检测纤溶酶抗纤溶酶复合物等纤溶生物标志物;最后本研究定义LY30 < 0.8%为SD,但并未进一步将低纤溶表型分类。

综上所述,严重创伤患者早期及初期复苏后均以SD、PY为主,HF发生率低,但病死率高;SD较PY患者病死率高,初期复苏后处于持续SD状态是严重创伤患者28 d死亡的危险因素。建议动态检测严重创伤患者早期的纤溶状态,为纠正纤溶失调提供帮助,以期进一步改善预后。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 张璐平:研究设计、统计学分析、论文撰写;杨晨:研究设计;姜俭:行政支持;高叶:血栓弹力图质量控制;邵荣海:实施研究、采集数据;刘励军:研究设计指导、论文修改

| [1] | Moore E, Moore H, Kornblith L, et al. Trauma-induced coagulopathy[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2021, 7: 1-23. DOI:10.1038/s41572-021-00264-3 |

| [2] | CRASH- trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2010, 376(9734): 23-32. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5 |

| [3] | Rossaint R, Afshari A, Bouillon B, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: sixth edition[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 80. DOI:10.1186/s13054-023-04327-7 |

| [4] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Gonzalez E, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis, physiologic fibrinolysis, and fibrinolysis shutdown: the spectrum of postinjury fibrinolysis and relevance to antifibrinolytic therapy[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2014, 77(6) 811-817, discussion 817. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000000341 |

| [5] | Rossetto A, Vulliamy P, Lee KM, et al. Temporal transitions in fibrinolysis after trauma: adverse outcome is principally related to late hypofibrinolysis[J]. Anesthesiology, 2022, 136(1): 148-161. DOI:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004036 |

| [6] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Neal MD, et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown in trauma: historical review and clinical implications[J]. Anesth Analg, 2019, 129(3): 762-773. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004234 |

| [7] | Meizoso JP, Karcutskie CA, Ray JJ, et al. Persistent fibrinolysis shutdown is associated with increased mortality in severely injured trauma patients[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2017, 224(4): 575-582. DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.018 |

| [8] | Collaborators C3 T. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10210): 1713-1723. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0 |

| [9] | Leeper CM, Neal MD, McKenna CJ, et al. Trending fibrinolytic dysregulation: fibrinolysis shutdown in the days after injury is associated with poor outcome in severely injured children[J]. Ann Surg, 2017, 266(3): 508-515. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002355 |

| [10] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Chapman MP, et al. Plasma-first resuscitation to treat haemorrhagic shock during emergency ground transportation in an urban area: a randomised trial[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10144): 283-291. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31553-8 |

| [11] | 中国医师协会急诊分会, 中国人民解放军急救医学专业委员会, 中国人民解放军重症医学专业委员会, 等. 创伤失血性休克诊治中国急诊专家共识[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2017, 26(12): 1358-1365. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2017.12.004 |

| [12] | 张玲玲, 朱凯, 陈剑, 等. 大量输血方案的研究进展[J]. 国际输血及血液学杂志, 2014, 37(5): 494-497. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-419X.2014.05.024 |

| [13] | 大量输血现状调研协作组. 大量输血指导方案(推荐稿)[J]. 中国输血杂志, 2012, 25(7): 617-621. DOI:10.13303/j.cjbt.issn.1004-549x.2012.07.011 |

| [14] | Moreno R, Vincent JL, Matos R, et al. The use of maximum SOFA score to quantify organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care. Results of a prospective, multicentre study. Working Group on Sepsis related Problems of the ESICM[J]. Intensive Care Med, 1999, 25(7): 686-696. DOI:10.1007/s001340050931 |

| [15] | Meizoso JP, Dudaryk R, Mulder MB, et al. Increased risk of fibrinolysis shutdown among severely injured trauma patients receiving tranexamic acid[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2018, 84(3): 426-432. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000001792 |

| [16] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Liras IN, et al. Acute fibrinolysis shutdown after injury occurs frequently and increases mortality: a multicenter evaluation of 2, 540 severely injured patients[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2016, 222(4): 347-355. DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.01.006 |

| [17] | Cardenas JC, Matijevic N, Baer LA, et al. Elevated tissue plasminogen activator and reduced plasminogen activator inhibitor promote hyperfibrinolysis in trauma patients[J]. Shock, 2014, 41(6): 514-521. DOI:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000161 |

| [18] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Gonzalez E, et al. Reperfusion shutdown: delayed onset of fibrinolysis resistance after resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock is associated with increased circulating levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and postinjury complications[J]. Blood, 2016, 128(22): 206. DOI:10.1182/blood.V128.22.206.206 |

| [19] | Leeper CM, Neal MD, McKenna C, et al. Abnormalities in fibrinolysis at the time of admission are associated with deep vein thrombosis, mortality, and disability in a pediatric trauma population[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2017, 82(1): 27-34. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000001308 |

| [20] | Cardenas JC, Wade CE, Cotton BA, et al. TEG Lysis shutdown represents coagulopathy in bleeding trauma patients: analysis of the PROPPR cohort[J]. Shock, 2019, 51(3): 273-283. DOI:10.1097/SHK.0000000000001160 |

| [21] | Moore HB, Moore EE, Huebner BR, et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown is associated with a fivefold increase in mortality in trauma patients lacking hypersensitivity to tissue plasminogen activator[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2017, 83(6): 1014-1022. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000001718 |

| [22] | Gall LS, Vulliamy P, Gillespie S, et al. The S100A10 pathway mediates an occult hyperfibrinolytic subtype in trauma patients[J]. Ann Surg, 2019, 269(6): 1184-1191. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002733 |

| [23] | Durbin S, Brito A, Johnson A, et al. Association of fibrinolysis phenotype with patient outcomes following traumatic brain injury[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2024, 96(3): 482-486. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000004122 |

| [24] | Guyette FX, Brown JB, Zenati MS, et al. Tranexamic acid during prehospital transport in patients at risk for hemorrhage after injury: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Surg, 2020, 156(1): 11-20. DOI:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4350 |

| [25] | Maegele M, Schöchl H, Menovsky T, et al. Coagulopathy and haemorrhagic progression in traumatic brain injury: advances in mechanisms, diagnosis, and management[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2017, 16(8): 630-647. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30197-7 |

| [26] | Roberts DJ, Kalkwarf KJ, Moore HB, et al. Time course and outcomes associated with transient versus persistent fibrinolytic phenotypes after injury: a nested, prospective, multicenter cohort study[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2019, 86(2): 206-213. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000002099 |

| [27] | Bennett B, Croll A, Ferguson K, et al. Complexing of tissue plasminogen activator with PAI-1, alpha 2-macroglobulin, and C1-inhibitor: studies in patients with defibrination and a fibrinolytic state after electroshock or complicated labor[J]. Blood, 1990, 75(3): 671-676. |

| [28] | Dixon AL, McCully BH, Rick EA, et al. Tranexamic acid administration in the field does not affect admission thromboelastography after traumatic brain injury[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2020, 89(5): 900-907. DOI:10.1097/TA.0000000000002932 |

2025, Vol. 34

2025, Vol. 34