2. 南部战区海军第一医院烧创伤医学科,湛江 524000

2. Department of Burn and Trauma Medicine, The First Naval Hospital of Southern Theater of Operations, Zhanjiang 524000, China

急性胰腺炎(acute pancreatitis,AP)是常见的消化系统疾病,目前全球发病率为每年34/10万,总体病死率在1%~5%之间 [1];其中约20%的AP患者会进展为重症急性胰腺炎(severe acute pancreatitis,SAP),病情凶险,病死率可达30% [2]。因此早期识别可能发展为SAP的患者对于指导临床决策意义重大。目前,临床常用的评分系统有CT严重指数评分(CT severity index,CTSI)、Ranson评分、急性胰腺炎严重程度床旁指数(bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis,BISAP)、急性生理学评估慢性健康评价Ⅱ(APACHE Ⅱ)评分等,但现有评分系统存在依赖指标多、计算繁琐、临床操作困难,耗时久等问题,需要更优化的预测模型来实现早期预测SAP的目标。最小绝对收缩与选择算子(least absolute shrinkage and selection operator,LASSO)回归[3]通过构造惩罚函数压缩存在多重共线性的自变量,在处理自变量过多而样本量较小的数据时具有明显的优势;Logistic回归模型对于自变量有较好的解释度,因此广泛用于临床预测模型的构建 [4];决策树模型由于其直观性、可解释性和可操作性,近年来也开始受到广泛关注。本文提取入院24 h内常规、快速、易得的临床指标, 基于LASSO回归对自变量进行初筛后分别构建Logistic回归模型和决策树模型,综合分析两种模型对于SAP早期预测的效果,为高危人群的识别和干预提供合理建议。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象选择2020年11月1日至2023年9月31日安徽医科大学第一附属医院本部及高新院区急诊科和消化内科收治的AP患者,根据病历系统及影像系统收集病例资料。纳入标准:年龄≥18周岁;符合《中国急性胰腺炎诊治指南》AP诊断标准 [5];排除标准:年龄 < 18岁,发病时间 > 48 h, 妊娠期,合并慢性肝炎、肝硬化、肝衰竭,慢性肾病、肾衰竭等肝肾功能不全;合并白血病、再生障碍性贫血等血液病;既往有放化疗史;既往有胰腺肿瘤、胰腺切除术、胰腺导管内乳头状黏液瘤等胰腺相关疾病。AP的严重程度依据2012年修订版亚特兰大分级(revised Atlanta classification,RAC)[6]。本研究符合医学伦理学标准,已经过安徽医科大学第一附属医院医学伦理委员会审查通过(审批号:PJ2022-03-16),所有检查和治疗均获得过患者及家属的知情同意。

1.2 数据收集通过查阅归档的电子病历,收集患者的一般资料,包括性别、年龄、体重指数、既往史(糖尿病、高血压、高脂血症、脂肪肝、胰腺炎病史)、病因(胆源型、高脂血症型、酒精型、其他);入院时的基本生命体征资料(意识、体温、心率、呼吸频率等);入院24h内实验室指标(血常规、凝血功能、肝肾功能等)和影像资料(超声、CT等);入院24 h内BISAP评分、视觉模拟评分法(visual analogue scale, VAS)疼痛评分。

1.3 统计学方法应用SPSS29.0和R4.3.1软件进行数据处理和统计分析:分类变量以频数和百分比表示(%)表示,采用χ2检验比较组间差异;符合正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,采用成组t检验比较组间差异;不符合正态分布的计量资料以中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1,Q3)]表示,采用非参数检验比较组间差异。双侧P < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义。使用R4.3.1软件的glmnet包,采用LASSO回归对变量进行筛选,依据距离最小偏差模型一个方差(SE)范围内得到的最简单模型保留自变量。基于caret包,运用10折交叉验证法在训练集中构建多因素Logistic回归模型,通过诺模图(Nomogram)展示最终模型中各个变量之间的相互关系和对结局变量的影响。通过10折交叉验证法构建决策树模型,计算各变量相对重要性,根据最佳复杂度参数值(complexity parameter, CP值)选择最终的决策树模型。分别使用训练集和测试集数据,采用敏感度、特异度、准确度及ROC曲线下面积(area under the ROC curve,AUC)、Kappa值评价模型效能,Delong检验比较Logistic回归模型和决策树模型及目前常用的BISAP评分的AUC差异。

2 结果 2.1 基线资料比较在研究期间,共纳入412例诊断为AP的患者:其中包括重症急性胰腺炎(SAP)(n=50)和非重症急性胰腺炎(NSAP=MAP+MSAP,n=362),SAP发生率12.14%。组间单因素差异比较显示:纳入49个自变量,共有31个自变量存在组间差异(表 1); 全部患者按7:3的比例随机分为训练集(n=292)和测试集(n=120),用于后续构建Logistic回归和决策树模型。对于训练集和测试集的数据进行比较,显示各个变量之间差异均无统计学意义,数据一致性较好(表 2)。

| 变量 | NSAP (n=362) | SAP (n=50) | Z/χ2 /t | P值 |

| 发病次数 | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.689 | 0.091 |

| 发病时间(n, %) | 1.980 | 0.160 | ||

| < 24 h | 250 (69.1) | 29 (58) | ||

| 24~48 h | 112 (30.9) | 21 (42) | ||

| 病因(n, %) | 8.440 | 0.038 | ||

| 胆源性 | 179 (49.4) | 35 (70) | ||

| 高脂性 | 87 (24) | 8 (16) | ||

| 酒精性 | 17 (4.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| 其他 | 79 (21.8) | 7 (14) | ||

| 性别(n, %) | 0.097 | 0.756 | ||

| 女 | 154 (42.5) | 23 (46) | ||

| 男 | 208 (57.5) | 27 (54) | ||

| 年龄(岁) | 50.0 (37.0, 64.0) | 54.0 (39.0, 70.0) | -1.460 | 0.144 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 24.7 ± 4.0 | 25.0 ± 4.1 | -0.456 | 0.650 |

| 吸烟(n, %) | 1.930 | 0.165 | ||

| 否 | 259 (71.5) | 41 (82) | ||

| 是 | 103 (28.5) | 9 (18) | ||

| 饮酒(n, %) | 1.930 | 0.165 | ||

| 否 | 243 (67.1) | 39 (78) | ||

| 是 | 119 (32.9) | 11 (22) | ||

| 肥胖(n, %) | 0.070 | 0.792 | ||

| 否 | 327 (90.3) | 44 (88) | ||

| 是 | 35 (9.7) | 6 (12) | ||

| 高血压(n, %) | 7.520 | 0.006 | ||

| 否 | 255 (70.4) | 25 (50) | ||

| 是 | 107 (29.6) | 25 (50) | ||

| 高脂血症(n, %) | 0.033 | 0.857 | ||

| 否 | 252 (69.6) | 36 (72) | ||

| 是 | 110 (30.4) | 14 (28) | ||

| 脂肪肝(n, %) | 1.600 | 0.206 | ||

| 否 | 226 (62.4) | 26 (52) | ||

| 是 | 136 (37.6) | 24 (48) | ||

| 糖尿病(n, %) | 2.790 | 0.095 | ||

| 否 | 288 (79.6) | 34 (68) | ||

| 是 | 74 (20.4) | 16 (32) | ||

| 胆石症(n, %) | 5.850 | 0.016 | ||

| 否 | 186 (51.4) | 16 (32) | ||

| 是 | 176 (48.6) | 34 (68) | ||

| 入院体温(℃) | 36.6 (36.5, 36.9) | 36.8 (36.5, 37.1) | -2.296 | 0.022 |

| 入院心率(次/min) | 88.0 (76.0, 100.0) | 106.0 (92.0, 120.0) | -5.781 | < 0.001 |

| 入院呼吸频率(次/min) | 20.0 (19.0, 20.0) | 22.0 (20.0, 24.0) | -6.012 | < 0.001 |

| 入院疼痛评分 | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 4.0) | -4.373 | < 0.001 |

| 胸腔积液(n, %) | 79.700 | < 0.001 | ||

| 否 | 300 (82.9) | 12 (24) | ||

| 是 | 62 (17.1) | 38 (76) | ||

| BISAP评分 | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) | -8.073 | < 0.001 |

| WBC(×109/L) | 12.6 ± 4.4 | 15.3 ± 5.4 | -3.480 | < 0.001 |

| Plt(×109/L) | 203.0 (158.0, 250.0) | 184.5 (134.0, 238.0) | 1.425 | 0.154 |

| HCT(%) | 41.8 ± 5.7 | 41.6 ± 6.5 | 0.271 | 0.787 |

| N(×109/L) | 10.4 ± 4.3 | 13.4 ± 5.3 | -3.750 | < 0.001 |

| N% | 84.0 (77.3, 88.1) | 88.4 (83.1, 90.5) | -3.556 | < 0.001 |

| IG(×109/L) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | -2.548 | 0.011 |

| IG% | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.1) | -2.495 | 0.013 |

| L(×109/L) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.4) | 2.674 | 0.008 |

| L% | 9.9 (6.7, 15.6) | 6.8 (4.4, 10.3) | 3.544 | < 0.001 |

| PDW(fL) | 12.6 (10.8, 15.1) | 13.8 (11.6, 16.2) | -2.186 | 0.029 |

| RDW-CV(%) | 13.0 (12.5, 13.5) | 13.6 (12.9, 14.5) | -3.386 | < 0.001 |

| RDW-SD(fL) | 42.2 (40.2, 44.9) | 44.0 (41.1, 46.8) | -2.561 | 0.010 |

| CRP(mg/L) | 15.6 (3.1, 75.2) | 152.1 (31.5, 244.6) | -6.447 | < 0.001 |

| D二聚体(mg/L) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | 2.8 (1.8, 8.4) | -6.509 | < 0.001 |

| FDP(mg/L) | 5.1 (2.6, 8.9) | 17.2 (6.1, 36.5) | -6.253 | < 0.001 |

| FIB(g/L) | 3.8 (3.1, 5.0) | 5.5 (4.0, 6.3) | -4.312 | < 0.001 |

| PT(s) | 13.2 (12.3, 14.0) | 14.5 (13.2, 15.1) | -4.786 | < 0.001 |

| APTT(s) | 33.0 ± 5.7 | 35.6 ± 6.1 | -2.820 | 0.006 |

| 胰淀粉酶(U/L) | 545.5 (187.0, 1242.0) | 610.5 (337.0, 1148.0) | -0.567 | 0.571 |

| 胰脂肪酶(U/L) | 1807.5 (854.0, 3759.0) | 1681.0 (832.0, 3390.0) | 0.260 | 0.796 |

| 血糖(mmol/L) | 7.5 (6.2, 10.6) | 10.2 (7.6, 12.8) | -3.803 | < 0.001 |

| Ca(mmol/L) | 2.1 (2.0, 2.3) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.1) | 6.433 | < 0.001 |

| BUN(mmol/L) | 5.2 (4.2, 6.5) | 6.9 (4.8, 11.0) | -3.826 | < 0.001 |

| Cr(mmol/L) | 61.8 (49.4, 74.4) | 81.6 (54.5, 132.6) | -4.161 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR(mL·min-1·1.73 m-2) | 112.5 (97.0, 125.0) | 91.5 (52.0, 117.0) | 4.331 | < 0.001 |

| Alb(g/L) | 44.2 (40.1, 46.8) | 35.3 (32.0, 40.1) | 6.317 | < 0.001 |

| TBil (μmol/L) | 21.6 (14.9, 37.9) | 26.9 (18.5, 42.5) | -1.655 | 0.098 |

| ALT(U/L) | 49.0 (26.0, 157.0) | 62.5 (25.0, 182.0) | -0.462 | 0.644 |

| AST(U/L) | 45.0 (27.0, 185.0) | 80.0 (33.0, 192.0) | -1.513 | 0.130 |

| ALP(U/L) | 104.5 (81.0, 146.0) | 111.0 (77.0, 161.0) | -0.694 | 0.488 |

| 注:BMI:体重指数;WBC:红细胞;Plt: 血小板;HCT:红细胞压积;N:中性粒细胞;N%:中性粒细胞百分比;IG: 幼稚粒细胞;IG%: 幼稚粒细胞百分比;L:淋巴细胞;L%: 淋巴细胞百分比;PDW:血小板分布宽度;RDW-CV:红细胞分布宽度变异系数;RDW-SD:红细胞分布宽度标准差;CRP:C反应蛋白;FDP:纤维蛋白降解产物;FIB:纤维蛋白原; PT: 凝血酶原时间; APTT: 活化部分凝血活酶时间; Ca: 血清钙;BUN:血尿素氮;Cr:血肌酐;eGFR:估计肾小球滤过率;Alb:血清白蛋白;TBil:总胆红素;ALT:谷丙转氨酶;AST:谷草转氨酶;ALP:碱性磷酸酶 | ||||

| 变量 | 测试集(n=120) | 训练集(n=292) | Z/χ2 /t值 | P值 |

| 发病次数 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | -1.247 | 0.213 |

| 发病时间(n, %) | 0.003 | 0.956 | ||

| < 24 h | 82 (68.3) | 197 (67.5) | ||

| 24~48 h | 38 (31.7) | 95 (32.5) | ||

| 病因(n, %) | 0.420 | 0.936 | ||

| 胆源性 | 63 (52.5) | 151 (51.7) | ||

| 高脂性 | 29 (24.2) | 66 (22.6) | ||

| 酒精性 | 4 (3.3) | 13 (4.5) | ||

| 其他 | 24 (20) | 62 (21.2) | ||

| 性别(n, %) | 0.747 | 0.387 | ||

| 女 | 56 (46.7) | 121 (41.4) | ||

| 男 | 64 (53.3) | 171 (58.6) | ||

| 年龄(岁) | 52.0 (39.0, 64.0) | 50.0 (37.0, 65.0) | 0.488 | 0.626 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 4.3 | 24.7 ± 3.9 | 0.427 | 0.670 |

| 吸烟(n, %) | 0.579 | 0.447 | ||

| 否 | 91 (75.8) | 209 (71.6) | ||

| 是 | 29 (24.2) | 83 (28.4) | ||

| 饮酒(n, %) | 1.730 | 0.189 | ||

| 否 | 76 (63.3) | 206 (70.5) | ||

| 是 | 44 (36.7) | 86 (29.5) | ||

| 肥胖(n, %) | 0.319 | 0.572 | ||

| 否 | 106 (88.3) | 265 (90.8) | ||

| 是 | 14 (11.7) | 27 (9.2) | ||

| 高血压(n, %) | 0.228 | 0.633 | ||

| 否 | 79 (65.8) | 201 (68.8) | ||

| 是 | 41 (34.2) | 91 (31.2) | ||

| 高脂血症(n, %) | 0.107 | 0.744 | ||

| 否 | 82 (68.3) | 206 (70.5) | ||

| 是 | 38 (31.7) | 86 (29.5) | ||

| 脂肪肝(n, %) | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 否 | 73 (60.8) | 179 (61.3) | ||

| 是 | 47 (39.2) | 113 (38.7) | ||

| 糖尿病(n, %) | 2.250 | 0.134 | ||

| 否 | 100 (83.3) | 222 (76) | ||

| 是 | 20 (16.7) | 70 (24) | ||

| 胆石症(n, %) | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 否 | 59 (49.2) | 143 (49) | ||

| 是 | 61 (50.8) | 149 (51) | ||

| 入院体温(℃) | 36.6 (36.5, 37.0) | 36.6 (36.5, 36.9) | 0.337 | 0.737 |

| 入院心率(次/min) | 88.0 (80.0, 100.0) | 88.0 (76.0, 104.0) | -0.148 | 0.883 |

| 入院呼吸频率(次/min) | 20.0 (19.0, 21.0) | 20.0 (19.0, 21.0) | 1.440 | 0.150 |

| 入院疼痛评分 | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) | 0.370 | 0.712 |

| 胸腔积液(n, %) | 3.480 | 0.062 | ||

| 否 | 83 (69.2%) | 229 (78.4%) | ||

| 是 | 37 (30.8%) | 63 (21.6%) | ||

| BISAP评分 | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 1.167 | 0.243 |

| WBC(×109/L) | 12.8 ± 4.2 | 12.9 ± 4.8 | -0.141 | 0.888 |

| Plt(×109/L) | 209.0 ± 81.5 | 209.8 ± 83.1 | -0.086 | 0.932 |

| HCT(%) | 41.3 ± 5.7 | 42.0 ± 5.8 | -1.240 | 0.218 |

| N(×109/L) | 10.7 ± 4.1 | 10.8 ± 4.7 | -0.329 | 0.742 |

| N% | 84.0 (78.5, 88.6) | 84.5 (77.5, 88.7) | -0.127 | 0.899 |

| IG(×109/L) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 0.668 | 0.504 |

| IG% | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 1.210 | 0.226 |

| L(×109/L) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | -0.033 | 0.974 |

| L% | 9.4 (6.3, 14.5) | 9.6 (6.0, 15.3) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| PDW(fL) | 12.9 (11.4, 15.5) | 12.6 (10.9, 15.4) | 0.613 | 0.540 |

| RDW_CV(%) | 13.0 (12.6, 13.8) | 13.0 (12.5, 13.6) | 0.497 | 0.619 |

| RDW_SD(fL) | 42.5 (40.7, 45.5) | 42.2 (40.0, 45.3) | 1.112 | 0.266 |

| CRP(mg/L) | 21.9 (4.9, 126.8) | 22.3 (3.2, 106.2) | 0.756 | 0.450 |

| D二聚体(mg/L) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.5) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.5) | 0.192 | 0.848 |

| FDP(mg/L) | 5.1 (2.5, 11.7) | 5.7 (2.9, 10.5) | -0.393 | 0.694 |

| FIB(g/L) | 4.0 (3.2, 5.4) | 3.9 (3.1, 5.1) | 0.710 | 0.478 |

| PT(s) | 13.3 (12.6, 14.2) | 13.3 (12.2, 14.1) | 0.654 | 0.514 |

| APTT(s) | 33.2 ± 4.9 | 33.4 ± 6.1 | -0.428 | 0.669 |

| 胰淀粉酶(U/L) | 651.5 (221.0, 1323.5) | 537.5 (179.0, 1168.0) | 0.692 | 0.489 |

| 胰脂肪酶(U/L) | 1886.0 (957.5, 3644.5) | 1772.0 (779.5, 3745.5) | 0.329 | 0.743 |

| 血糖(mmol/L) | 7.5 (6.2, 10.8) | 7.8 (6.4, 10.8) | -0.902 | 0.368 |

| Ca(mmol/L) | 2.1 (2.0, 2.2) | 2.1 (2.0, 2.2) | -0.903 | 0.367 |

| BUN(mmol/L) | 5.1 (4.3, 6.7) | 5.3 (4.2, 6.8) | -0.180 | 0.857 |

| Cr(mmol/L) | 63.4 (50.3, 78.1) | 63.0 (50.8, 76.4) | 0.216 | 0.829 |

| eGFR(mL·min-1·1.73 m-2) | 111.5 (97.0, 123.0) | 110.0 (93.0, 125.0) | -0.004 | 0.997 |

| Alb(g/L) | 43.3 (38.2, 46.4) | 43.7 (38.8, 46.7) | -0.155 | 0.877 |

| TBil (μmol/L) | 24.1 (16.4, 42.7) | 20.8 (14.7, 36.6) | 1.359 | 0.174 |

| ALT(U/L) | 53.5 (28.5, 175.5) | 47.0 (25.0, 139.0) | 0.951 | 0.342 |

| AST(U/L) | 49.5 (32.0, 223.5) | 45.0 (27.0, 168.5) | 1.737 | 0.083 |

| ALP(U/L) | 108.5 (82.0, 159.5) | 104.5 (80.0, 144.5) | 0.421 | 0.674 |

| 注:BMI:体重指数;WBC:红细胞;Plt: 血小板;HCT:红细胞压积;N:中性粒细胞;N%:中性粒细胞百分比;IG: 幼稚粒细胞;IG%: 幼稚粒细胞百分比;L:淋巴细胞;L%: 淋巴细胞百分比;PDW:血小板分布宽度;RDW-CV:红细胞分布宽度变异系数;RDW-SD:红细胞分布宽度标准差;CRP:C反应蛋白;FDP:纤维蛋白降解产物;FIB:纤维蛋白原; PT: 凝血酶原时间; APTT: 活化部分凝血活酶时间; Ca: 血清钙;BUN:血尿素氮;Cr:血肌酐;eGFR:估计肾小球滤过率;Alb:血清白蛋白;TBil:总胆红素;ALT:谷丙转氨酶;AST:谷草转氨酶;ALP:碱性磷酸酶 | ||||

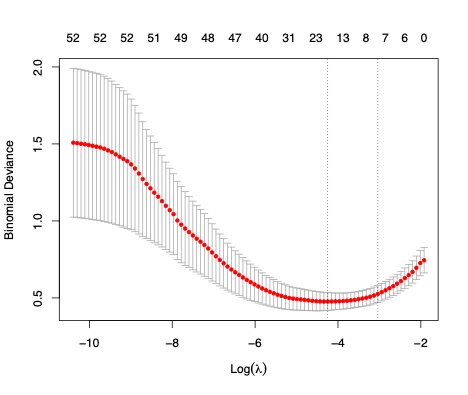

基于全体数据,纳入待筛选的全部自变量(49个),经过哑变量转换后得到52个自变量进入LASSO回归,按照lambda.1se变量筛选准则,最终在λ取值0.048 [log(λ) ≈-3.038]时获得兼顾较好性能且自变量个数最少的模型(图 1),筛选出7个与SAP发生相关性最显著的变量,包括:入院呼吸频率、入院疼痛评分、胸腔积液、纤维蛋白降解物(FDP)、C反应蛋白(CRP)、血肌酐(Cr)、血清白蛋白(Alb);与单因素差异分析比较,LASSO回归对大量存在差异的自变量进行了筛选。

|

| LASSO回归由参数lambda(λ)调整对模型复杂度的惩罚力度,λ越大则模型复杂度的惩罚力度越大。通过获取lambda.min和lambda.1se对应的自变量系数,可以对自变量进行有效的筛选:图中右侧虚线显示距离最佳模型偏差1se时对应的log(λ)取值和自变量个数 图 1 10折交叉验证拟合不同变量组合的LASSO回归模型参数 Fig 1 10-fold cross-validation of LASSO regression model parameters fitting different combinations of variables |

|

|

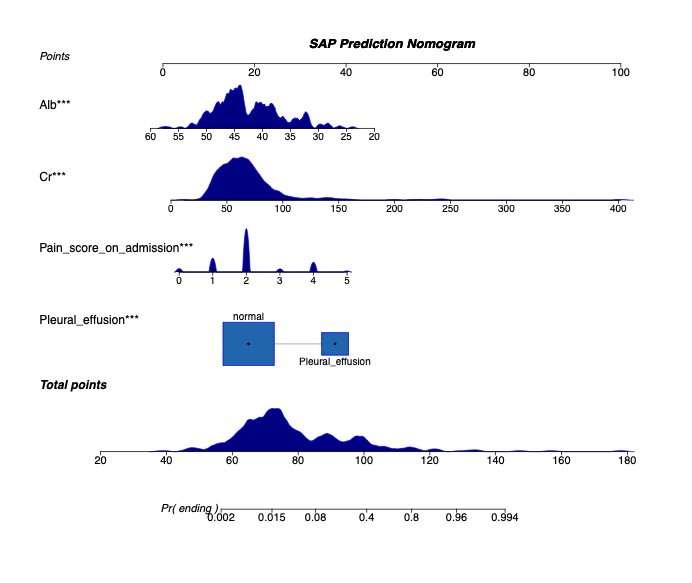

基于训练集的数据,将LASSO回归筛选出的显著变量进行多因素Logistic回归,通过10折交叉验证,保留多因素分析中有统计学意义的自变量(P < 0.05)构建模型:胸腔积液[OR(95%CI)=11.90(10.80~13.00), P < 0.001]、入院疼痛评分[OR(95%CI)=2.62(2.13~3.11), P < 0.001]、Cr[OR(95%CI)= 1.03(1.02 ~1.05), P < 0.001]、Alb[OR(95%CI)= 0.85(0.77~0.93), P < 0.001] (表 3)。SAP概率(PSAP =1)计算公式:Logit(PSAP =1)= -1.23+2.48×胸腔积液+0.96×入院疼痛评分+0.03×Cr-0.16×Alb,绘制诺模图(Nomogram)展示各变量之间的关系(图 2)。

| 指标 | β | SE | Z | P值 | OR(95%CI) |

| Intercept | -1.23 | 1.78 | -0.69 | 0.490 | 0.29(-3.19~3.78) |

| 胸腔积液 | 2.48 | 0.54 | 4.55 | < 0.001 | 11.90(10.80~13.00) |

| 入院疼痛评分 | 0.96 | 0.25 | 3.86 | < 0.001 | 2.62(2.13~3.11) |

| Cr | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.94 | < 0.001 | 1.03(1.02~1.05) |

| Alb | -0.16 | 0.04 | -3.91 | < 0.001 | 0.85(0.77~0.93) |

| 注:Cr:血肌酐;Alb:血清白蛋白 | |||||

|

| Alb:血清白蛋白;Cr: 血肌酐;Pain score on admission:入院疼痛评分;Pleural effusion:胸腔积液 图 2 多因素Logistic回归模型预测SAP的Nomogram Fig 2 Nomogram of SAP prediction by multi-factor Logistic regression model |

|

|

每个指标均可转换成分值(points), 根据患者的实际测量值对应标尺相应数值, 得到患者该指标的分值,累积计算总分(total points), 根据总分对应的结局概率Pr(ending)即可预测SAP发生的概率。

2.3.2 决策树模型基于训练集数据,使用LASSO回归筛选出的显著变量,通过10折交叉验证,构建决策树模型,并获得各节点的预测概率。

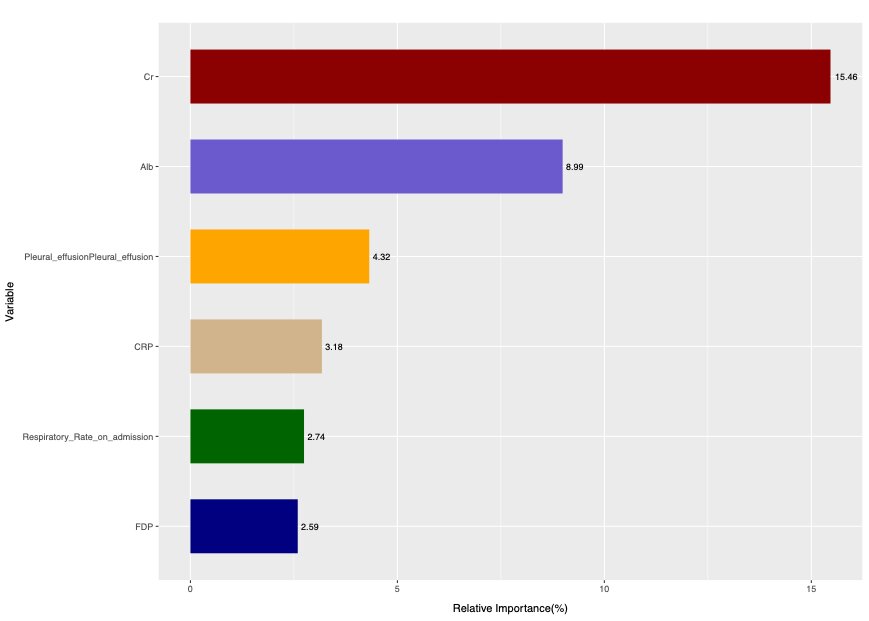

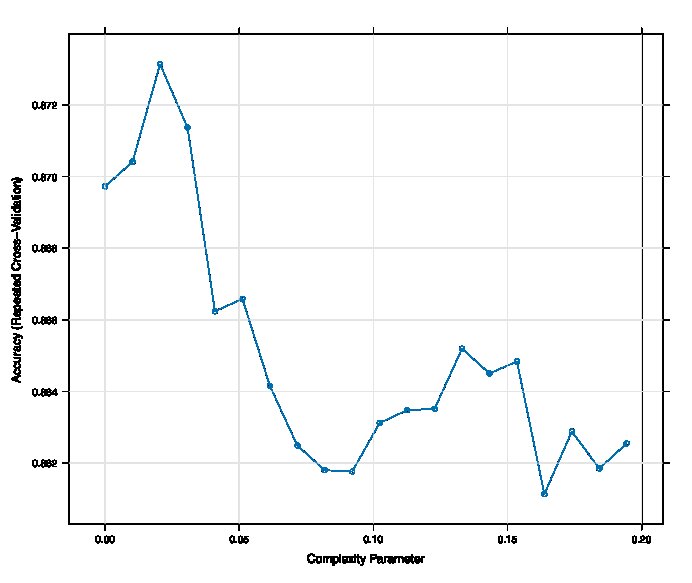

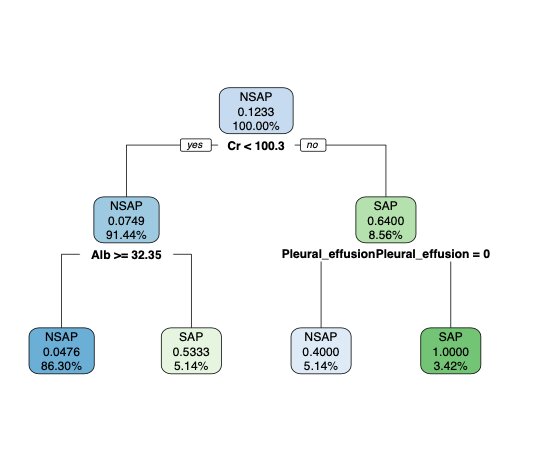

Caret包使用CART算法构建决策树,用基尼系数对模型中变量的相对重要性进行排序,并通过复杂度参数值(complexity Parameter, CP值)控制树的复杂度。基尼系数(Gini)结果显示:CART算法剔除了入院疼痛评分,其余变量对模型贡献的相对重要性如下:Cr(15.46)、Alb(8.99)、胸腔积液(4.32)、CRP(3.18)、入院呼吸频率(2.74)、FDP(2.59)(图 3)。可知,当CP值为0.020时,模型准确度最高(图 4),此时决策树仅保留了相对重要性排前3名的自变量(图 5),构成3个节点,每个节点分别展示了在当前条件下判断某个观测为SAP的条件概率和符合条件的人数占总人数的百分比,该节点条件概率大于0.5, 则判断为SAP,反之则判断为NSAP。

|

| Cr: 血肌酐; Alb:血清白蛋白;Pleural effusion:胸腔积液;CRP: C反应蛋白;Respiratory Rate on admission: 入院呼吸频率;FDP: 纤维蛋白降解物 图 3 基尼系数显示变量相对重要性排序 Fig 3 Gini coefficient shows the relative importance of variables |

|

|

|

| 图 4 Complexity Parameter筛选最佳决策树模型 Fig 4 Optimum decision tree model for Complexity Parameter screening |

|

|

|

| Cr:血肌酐;Pleural effusion:胸腔积液(0=无,1=有);Alb:血清白蛋白 图 5 决策树模型 Fig 5 Decision tree model |

|

|

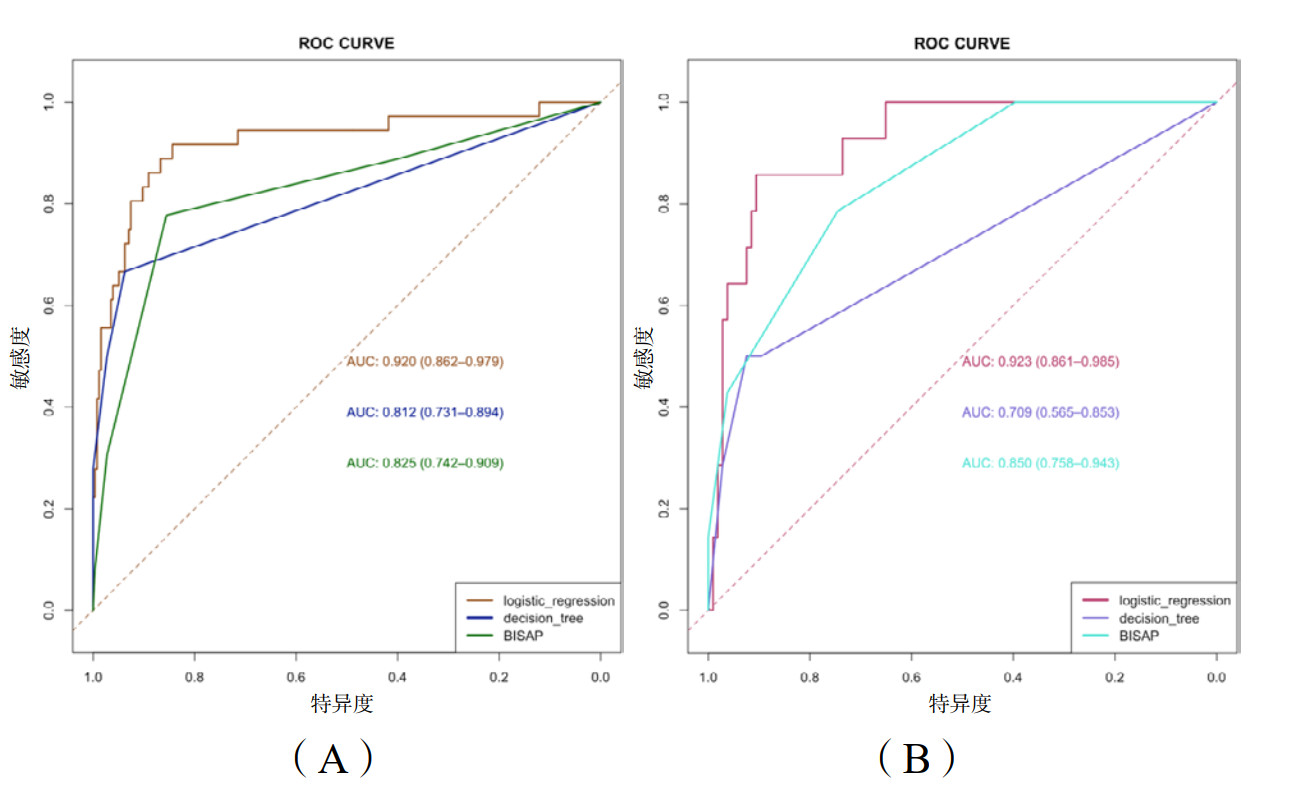

分别在训练集和测试集中比较Logistic回归模型、决策树模型和BISAP评分对SAP的预测效果(表 4)。训练集中,Logistic回归模型:敏感度=0.528, 特异度= 0.984, 准确度(95%CI)= 0.928(0.892~0.955), Kappa值= 0. 606;决策树模型:敏感度=0.500, 特异度= 0.973, 准确度(95%CI)= 0.914(0.876~0.944), Kappa值= 0.544。测试集中,Logistic回归模型:敏感度=0.643, 特异度= 0.925, 准确度(95%CI)= 0.891(0.822~0.941), Kappa值= 0.519;决策树模型:敏感度=0.500, 特异度= 0.925, 准确度(95%CI)= 0.875(0.802~0.928), Kappa值= 0.412。同时展示BISAP评分对SAP的预测效果,并绘制ROC曲线(图 6),通过Delong检验比较AUC差异的显著性(表 5):在训练集中,Logistic回归模型AUC大于决策树模型(P<0.01)和BISAP评分(P < 0.001),而决策树模型和BISAP评分的AUC差异无统计学意义(P=0.762);在测试集中,Logistic回归模型AUC同样大于决策树模型(P < 0.01)和BISAP评分(P=0.018),而决策树模型的AUC低于BISAP评分(P=0.017)。

| 模型 | AUC(95%CI) | 敏感度 | 特异度 | 准确度(95%CI) | Kappa值 |

| 训练集 | |||||

| Logistic | 0.920(0.862~0.979) | 0.528 | 0.984 | 0.928(0.892~0.955) | 0.606 |

| 决策树 | 0.812(0.731~0.894) | 0.500 | 0.973 | 0.914(0.876~0.944) | 0.544 |

| BISAP | 0.825(0.742~0.909) | 0.306 | 0.973 | 0.890(0.849~0.924) | 0.354 |

| 测试集 | |||||

| Logistic | 0.923(0.861~0.985) | 0.643 | 0.925 | 0.891(0.822~0.941) | 0.519 |

| 决策树 | 0.709(0.565~0.853) | 0.500 | 0.925 | 0.875(0.802~0.928) | 0.412 |

| BISAP | 0.850(0.758~0.943) | 0.429 | 0.962 | 0.900(0.832~0.947) | 0.446 |

|

| 图 6 预测SAP的ROC曲线:(A)训练集;(B)测试集 Fig 6 ROC curve for SAP prediction: (A) Training set; (B) Test sets |

|

|

| 项目 | 训练集 | 测试集 | ||

| 统计量(Z) | P值 | 统计量 | P值 | |

| Logistic vs.决策树 | 2.722 | < 0.01 | 3.429 | < 0.001 |

| Logistic vs. BISAP | 3.309 | < 0.001 | 2.361 | 0.018 |

| 决策树vs. BISAP | -0.303 | 0.762 | -2.382 | 0.017 |

LASSO回归通过正则化方法,在模型中增加惩罚项,将过小的回归系数压缩到0, 以一定估计偏差为代价获得更高的预测准确度和泛化能力,在处理众多变量和较小样本量的数据,以及变量之间存在多重共线性的问题时具有明显的优势[7],近来开始用于各类临床预测模型的变量筛选 [8-9]。本研究结果显示,相比较单因素分析中的显著自变量,LASSO回归对于变量进行了有效提炼。

Alb作为炎症的阴性指标,在众多炎性疾病中下降。AP患者中出现持续性器官衰竭(Persistent organ failure, POF)的,其入院时Alb水平明显低于无POF患者 [10]。研究显示:RDW/ Alb比率 [11]或传统的CRP/Alb比值 [12-13]均能有效预测SAP的发生。本研究两个模型均显示了Alb的重要预测价值,Logistic回归显示Alb降低是SAP的独立危险因素。

AP患者常伴明显的低蛋白血症,因此也常会导致胸腔积液(发生率约为34% [14],本研究中为24.27%)。尽管Alberti等[15]研究显示CTSI评分对判断胰腺炎严重程度、预测POF、死亡有一定意义,但何洋等[16]研究显示预测SAP的灵敏度和特异度均一般。CTSI需要增强CT才能明确,且发病初期胰腺影像特征往往难以反应病情严重程度[5],因此不推荐用于早期快速预测。相对而言,胸腔积液仅需CT平扫即可以获得诊断,可替代CTSI作为简便和有效的早期SAP预测指标。更有证实,胸腔积液也是AP患者肾功能衰竭的独立风险因素 [17]。本研究的Logistic回归模型和决策树模型均纳入了入院24 h内CT诊断的胸腔积液,需要早期密切关注和干预, 及时穿刺积液引流和床旁超声动态监测尤为重要[18]。

急性肾损伤(acute kidney injury,AKI)是AP的常见并发症,15%~70%的SAP患者会发生AKI [19],且显著增加死亡风险[20]。有研究显示Cr和Alb比值可以作为AP患者短期和长期全因病死率的独立预测指标[21]。已有学者使用Cr、胸腔积液、肾旁后间隙受累和血清钙离子浓度构建SAP预测模型(AUC=0.905, 95%CI: 0.869~0.933)[22],本研究也印证了此结论。早期干预AP以抑制炎症反应,防止脏器功能损伤,尤其预防并发AKI,对于改善预后有重要意义。

疼痛是临床常规监测的第五大生命体征,也是急性胰腺炎的典型症状。胰腺损伤释放的炎性介质可以传递痛觉信号,而疼痛本身又促进神经系统释放神经源性介质,加剧胰腺损伤[23]。研究表明SAP的发生与入院时疼痛的剧烈程度相关[24],而与入院时疼痛持续时间是否有关则存在争议[25];本研究也证实入院疼痛评分是SAP发生的独立危险因素。多模态、个体化、结合药物和硬膜外镇痛的治疗方案能够减轻胰腺组织损伤,起到胰腺保护作用,改善患者预后[26]。医护人员应提高对疼痛管理的意识,加强对AP患者疼痛管理与监护。

决策树模型的基尼系数显示FDP在SAP早期预测中亦有一定重要性。AP产生的全身炎症反应,会使得促炎和抗炎细胞因子均升高,导致微血管血栓形成和高凝状态 [27]。微血管变化和凝血激活与AP严重程度密切相关[28]。在AP患者中,FDP的动态变化是AP相关病死率和器官衰竭的良好预测因素[29];回顾性研究也显示系统性抗凝治疗对改善SAP预后有益[30]。除前述CRP/Alb比值外,CRP本身作为阳性急性期蛋白,是SAP的独立预测因子。国外指南 [31]指出发病72 h内CRP水平大于150 mg/dL提示SAP。尽管没有纳入本研究的最终模型,但不可忽视早期传统血清的生物标志物和AP患者预后之间的联系。

本研究通过LASSO回归筛选变量,分别基于Logistic回归和决策树构建SAP预测模型,模型指标均为入院时急诊患者的常规检查,获取简单廉价且方便快捷。BISAP评分在本数据集中也有较好的预测效果,但评分项目较多,且敏感度过低,会造成漏诊,这与前人研究结果一致 [32-33]。相较而言,Logistic回归模型具有很好的预测效能和稳健性;决策树模型可视化程度高,流程简单,更适合临床简单快速使用,但在测试集中表现略下降,稳健性稍差。两个模型均对医护人员快速评估病情有一定指导作用,为SAP早期干预和并发症预防提供了客观参考依据。

本研究的局限性在于: (1)本研究为单中心观察性研究,预测结果可能会存在一定偏倚,且缺乏外部验证。今后应尝试联合多中心进行更大样本量的研究,以提高样本代表性和模型的泛化能力;(2)本研究作为回顾性研究,部分变量由于缺失过多而剔除,从而影响模型的预测准确性,也失去了对部分潜在变量作用探索的机会。今后的研究将尽可能前瞻性收集更多、更完善的变量信息。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 王梅:研究设计、实施,文章撰写;夏瑜:研究设计,数据统计分析和解释;武长美、马良慧、陈艳艳、朱文俊:数据收集、整理、核对;王兴宇:论文修改,经费支持

| [1] | Petrov MS, Yadav D. Global epidemiology and holistic prevention of pancreatitis[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16(3): 175-184. DOI:10.1038/s41575-018-0087-5 |

| [2] | Trikudanathan G, Wolbrink DRJ, van Santvoort HC, et al. Current concepts in severe acute and necrotizing pancreatitis: an evidence-based approach[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(7): 1994-2007.e3. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.269 |

| [3] | Ternès N, Rotolo F, Michiels S. Empirical extensions of the lasso penalty to reduce the false discovery rate in high-dimensional Cox regression models[J]. Stat Med, 2016, 35(15): 2561-2573. DOI:10.1002/sim.6927 |

| [4] | 王亚丹, 王苗苗, 郭春梅, 等. 急性胰腺炎严重程度早期预测模型的构建与验证[J]. 首都医科大学学报, 2023, 44(2): 302-310. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-7795.2023.02.018 |

| [5] | 中华医学会外科学分会胰腺外科学组. 中国急性胰腺炎诊治指南(2021)[J]. 浙江实用医学, 2021, 26(6) 511-519, 535. DOI:10.16794/j.cnki.cn33-1207/r.2021.06.003 |

| [6] | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis: 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(1): 102-111. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. |

| [7] | Wang S, Nan B, Rosset S, et al. Random lasso[J]. Ann Appl Stat, 2011, 5(1): 468-485. DOI:10.1214/10-aoas377 |

| [8] | Kang J, Choi YJ, Kim IK, et al. LASSO-based machine learning algorithm for prediction of lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal cancer[J]. Cancer Res Treat, 2021, 53(3): 773-783. DOI:10.4143/crt.2020.974 |

| [9] | Wang Q, Qiao WY, Zhang HH, et al. Nomogram established on account of Lasso-Cox regression for predicting recurrence in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 1019638. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1019638 |

| [10] | Li SK, Zhang YS, Li MJ, et al. Erratum to: Serum albumin, a good indicator of persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2017, 17(1): 86. DOI:10.1186/s12876-017-0645-2 |

| [11] | Wang XL, Zhu LY, Tao KL, et al. Red cell distribution width to serum albumin ratio as an early prognostic marker for severe acute pancreatitis: a retrospective study[J]. Arab J Gastroenterol, 2022, 23(3): 206-209. DOI:10.1016/j.ajg.2022.06.001 |

| [12] | Behera MK, Mishra D, Sahu MK, et al. C-reactive protein/albumin and ferritin as predictive markers for severity and mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. Prz Gastroenterol, 2023, 18(2): 168-174. DOI:10.5114/pg.2022.115609 |

| [13] | Haider Kazmi SJ, Zafar MT, Zia BF, et al. Role of serum C-reactive protein (CRP)/Albumin ratio in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort[J]. Ann Med Surg, 2022, 82: 104715. DOI:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104715 |

| [14] | Zeng TT, An J, Wu YQ, et al. Incidence and prognostic role of pleural effusion in patients with acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis[J]. Ann Med, 2023, 55(2): 2285909. DOI:10.1080/07853890.2023.2285909 |

| [15] | Alberti P, Pando E, Mata R, et al. Evaluation of the modified computed tomography severity index (MCTSI) and computed tomography severity index (CTSI) in predicting severity and clinical outcomes in acute pancreatitis[J]. J Dig Dis, 2021, 22(1): 41-48. DOI:10.1111/1751-2980.12961 |

| [16] | 何洋, 丁莺, 李金跃, 等. 急性胰腺炎患者早期CTSI评分与器官衰竭的相关性分析[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2023, 32(10): 1350-1352. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.10.010 |

| [17] | Zeng QX, Jiang KL, Wu ZH, et al. Pleural effusion is associated with severe renal dysfunction in patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2021, 27: e928118. DOI:10.12659/MSM.928118 |

| [18] | 郭丰. 重症急性胰腺炎呼吸衰竭的诊治思考[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2023, 32(10): 1287-1290. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.10.001 |

| [19] | Wajda J, Dumnicka P, Maraj M, et al. Potential prognostic markers of acute kidney injury in the early phase of acute pancreatitis[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(15): 3714. DOI:10.3390/ijms20153714 |

| [20] | Devani K, Charilaou P, Radadiya D, et al. Acute pancreatitis: Trends in outcomes and the role of acute kidney injury in mortality- A propensity-matched analysis[J]. Pancreatology, 2018, 18(8): 870-877. DOI:10.1016/j.pan.2018.10.002 |

| [21] | Wang JJ, Li H, Luo HW, et al. Association between serum creatinine to albumin ratio and short- and long-term all-cause mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis admitted to the intensive care unit: a retrospective analysis based on the MIMIC-Ⅳ database[J]. Front Immunol, 2024, 15: 1373371. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1373371 |

| [22] | 陈桥梁, 徐丹丹, 杨俊杰, 等. 平扫CT联合临床指标对重症急性胰腺炎预测价值的探讨[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2023, 32(10): 1333-1339. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.10.007 |

| [23] | Barreto SG, Saccone GT. Pancreatic nociception: revisiting the physiology and pathophysiology[J]. Pancreatology, 2012, 12(2): 104-112. DOI:10.1016/j.pan.2012.02.010 |

| [24] | Földi M, Gede N, Kiss S, et al. The characteristics and prognostic role of acute abdominal on-admission pain in acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort analysis of 1432 cases[J]. Eur J Pain, 2022, 26(3): 610-623. DOI:10.1002/ejp.1885 |

| [25] | Pandanaboyana S, Knoph CS, Olesen SS, et al. Opioid analgesia and severity of acute pancreatitis: an international multicentre cohort study on pain management in acute pancreatitis[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2024, 12(3): 326-338. DOI:10.1002/ueg2.12542 |

| [26] | 亚洲急危重症协会中国腹腔重症协作组. 重症急性胰腺炎镇痛治疗中国专家共识(2022版)[J]. 中华消化外科杂志, 2022, 21(12): 1499-1509. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn115610-20221110-00683 |

| [27] | Cuthbertson CM, Christophi C. Disturbances of the microcirculation in acute pancreatitis[J]. Br J Surg, 2006, 93(5): 518-530. DOI:10.1002/bjs.5316 |

| [28] | Tukiainen E, Kylänpää ML, Repo H, et al. Hemostatic gene polymorphisms in severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreas, 2009, 38(2): e43-6. DOI:10.1097/mpa.0b013e31819827ef |

| [29] | Liu CN, Zhou XF, Ling LQ, et al. Prediction of mortality and organ failure based on coagulation and fibrinolysis markers in patients with acute pancreatitis: a retrospective study[J]. Medicine, 2019, 98(21): e15648. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000015648 |

| [30] | Kröner PT, Wallace MB, Raimondo M, et al. Systemic anticoagulation is associated with decreased mortality and morbidity in acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2021, 21(8): 1428-1433. DOI:10.1016/j.pan.2021.09.003 |

| [31] | Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: management of acute pancreatitis[J]. Can J Surg, 2016, 59(2): 128-140. DOI:10.1503/cjs.015015 |

| [32] | Yang YX, Li L. Evaluating the ability of the bedside index for severity of acute pancreatitis score to predict severe acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis[J]. Med Princ Pract, 2016, 25(2): 137-142. DOI:10.1159/000441003 |

| [33] | Arif A, Jaleel F, Rashid K. Accuracy of BISAP score in prediction of severe acute pancreatitis[J]. Pak J Med Sci, 2019, 35(4): 1008-1012. DOI:10.12669/pjms.35.4.1286 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33