体外膜肺氧合(extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO)是一种高级体外生命支持技术,目前已越来越多地应用于成人心肺功能衰竭患者的抢救和治疗中[1]。ECMO治疗期间的患者管理直接影响预后,其中,能量摄入管理尤为重要但又常常被忽视。中国急诊危重症肠内营养治疗专家共识推荐急危重症患者的能量摄入目标为25~30 kcal/(kg·d),蛋白摄入目标为1.2~2.0 g/(kg·d)[2]。然而,能量摄入不足所致的营养不良仍是危重症患者常见的并发症,同时也与死亡密切相关[3-4]。目前重症监护室(intensive care unit, ICU)内常用的营养方式有肠内营养(enteral nutrition, EN)和肠外营养(parenteral nutrition, PN),其中早期(< 48 h)肠内营养(early enteral nutrition, EEN)可以显著改善危重症患者的预后[5]。目前数据显示能量摄入不足在ECMO患者中也很常见[6],同时,ECMO患者早期营养途径与其预后的关系尚不明确[7-9],危重症患者的能量标准是否适用于的ECMO患者也缺乏充足的证据[10]。本研究旨在探索早期能量摄入量及EEN对ECMO患者预后的影响。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象本研究为观察性、回顾性病例对照研究,纳入了2021年1月至2022年6月在南京医科大学第一附属医院(江苏省人民医院)拥有17张床位的急诊监护病房(emergency intensive care unit, EICU)内接受ECMO治疗的患者。研究方案经南京医科大学第一附属医院伦理委员会批准(批号:2023-SR-187),作为非干预性临床研究,获得了豁免知情同意。

1.2 纳入与排除标准纳入标准包括:①年龄≥18岁;②ECMO支持时间≥72 h;③入EICU后行常规治疗,包括Ⅰ级护理、呼吸循环支持、维持水电解质平衡,有感染者予抗感染治疗等。排除标准包括:①临床资料不全者;②存在甲状腺功能亢进、消化道系统疾病、结核病、恶性肿瘤等可能影响营养状态者。

1.3 研究分组依据患者每日每标准公斤体重能量摄入量,通过Logistic回归和限制性立方样条分析结果,依据OR=1对应的每日每标准公斤体重能量摄入量作为截断值,将未达到此数值的患者纳入能量欠缺组,达到此数值的患者纳入能量丰富组。依据患者开始ECMO治疗与初次使用EN之间的时间进行分组,< 48 h为EEN组,≥48 h为非EEN组。

1.4 资料收集收集患者以下资料:性别、年龄、身高、体重、原发疾病、ECMO使用模式、ECMO转机时间、ECMO开始至初次使用EN时间及预后情况。收集患者营养方式、各营养素(糖、脂质和蛋白)摄入情况,并按照标准体重校正计算患者接受ECMO后7 d(不足7 d者以转机时间计算)每日能量摄入量。

1.5 能量摄入的计算参照《中国急诊危重症肠内营养治疗专家共识》[2]采取同样的计算方式,先依据患者入院时的身高数据,通过标准体重公式:男性标准体重(kg)=[身高(cm)−80]×70%、女性标准体重=[身高(cm)−70]×60%,从而获取患者的标准体重;然后通过收集的总能量摄入及蛋白摄入的量与标准体重及营养天数之比,进而得出患者每日每标准公斤体重所摄入的能量及蛋白的量,单位为kcal/(kg·d)及g/(kg·d)。

1.6 统计学方法使用R 4.0.5和SPSS 27.0统计软件分析数据。计量资料进行正态性检验及方差齐性检验,正态分布及方差齐的计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验检验,非正态分布的计量资料以中位数(四分位数)[M(Q1, Q3)]表示,组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验;计数资料以频数(率)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。其次,结合使用Logistic回归分析及限制性立方样条(restricted cubic splines, RCS)的方法评估能量摄入量和蛋白摄入量对病死率的影响并将其可视化[11]。最后,使用Kaplan-Meier生存分析分别比较不同分组28 d存活率,并用log-rank检验进行比较。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

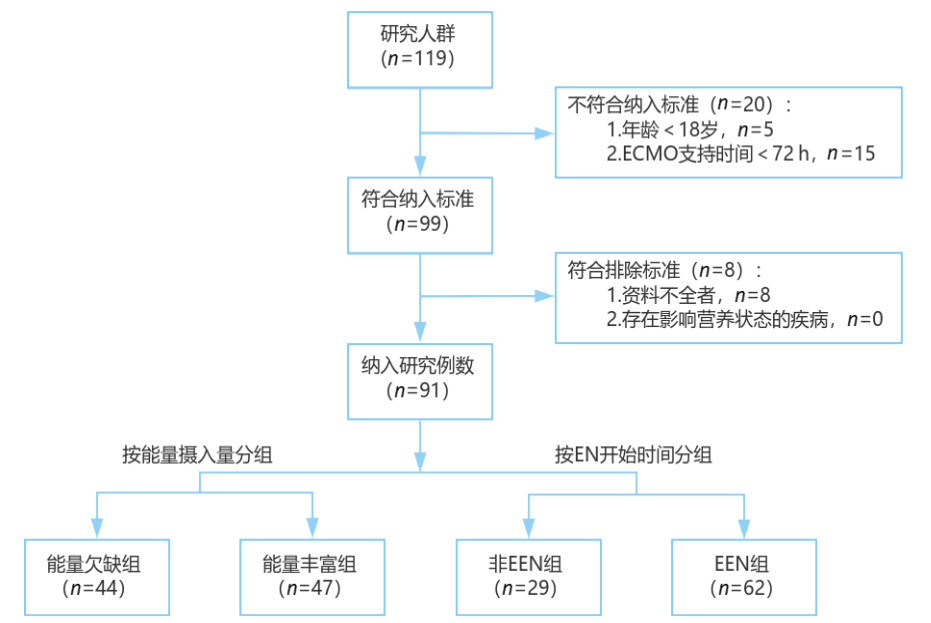

2 结果 2.1 研究人群特点2021年1月1日至2022年6月30日于南京医科大学第一附属医院接受ECMO治疗的患者总计119例,最终纳入91例,流程图见图 1。年龄(50.02±15.37)岁,男性64例(70.3%),BMI(24.59±3.29)kg/m2。ECMO模式中以体外心肺复苏(ECPR)模式居多,共43(47.3%)例;其次为静脉-动脉(VA)模式,共35(38.5%)例;转机时间为6.0(3.9, 9.1)d,住院时间为16(9, 28)d。原发疾病中以急性心肌梗死占比最多,共34例(37.4%);其次为暴发性心肌炎患者,共17例(18.7%)。

|

| 图 1 患者分组流程图 Fig 1 Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion of patients |

|

|

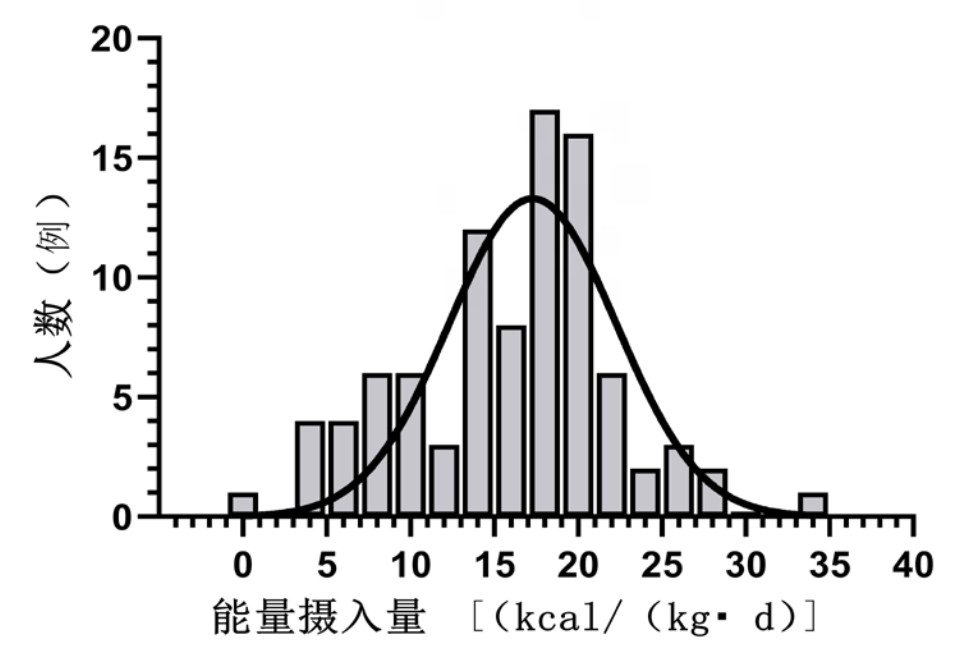

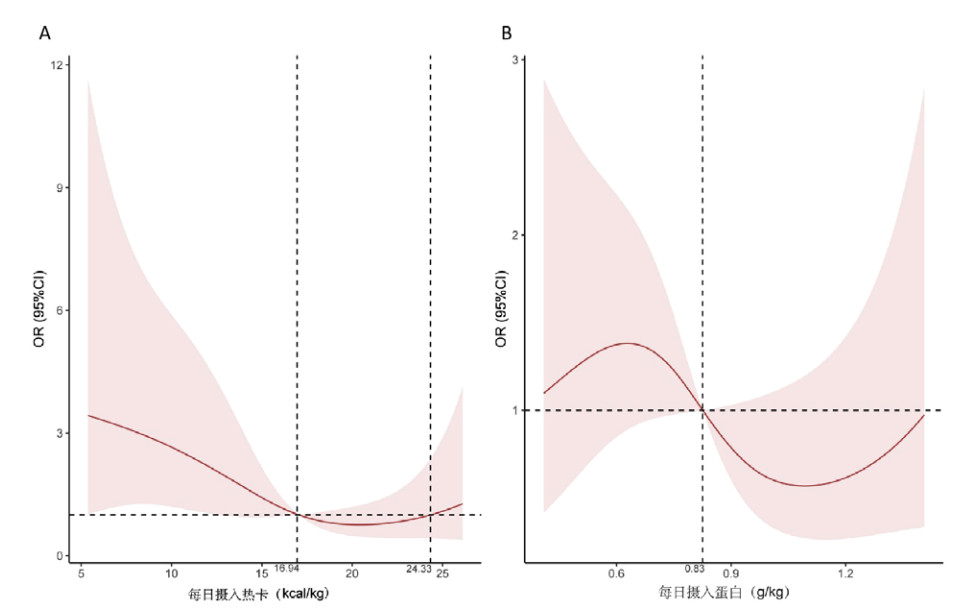

图 2显示了所有患者的能量摄入频数图,91例ECMO患者平均能量摄入量为(15.92±6.34)kcal/(kg·d),中位蛋白摄入量为0.83(0.69, 1.07) g/(kg·d)。Logistic和RCS分析显示患者能量摄入在16.94~24.33 kcal/(kg·d)之间对患者总体预后是保护性因素,蛋白摄入在 > 0.83 g/(kg·d)时对患者总体预后是保护性因素。每日每标准公斤体重能量、蛋白摄入与总体预后OR值见图 3。

|

| 图 2 每日每标准公斤体重能量摄入量频数图 Fig 2 Frequency chart of energy intake per standard body weight per day |

|

|

|

| 图 3 每日每标准公斤体重能量、蛋白摄入与总体预后OR值 Fig 3 The OR of daily energy and protein intake per standard body weight with overall prognostic |

|

|

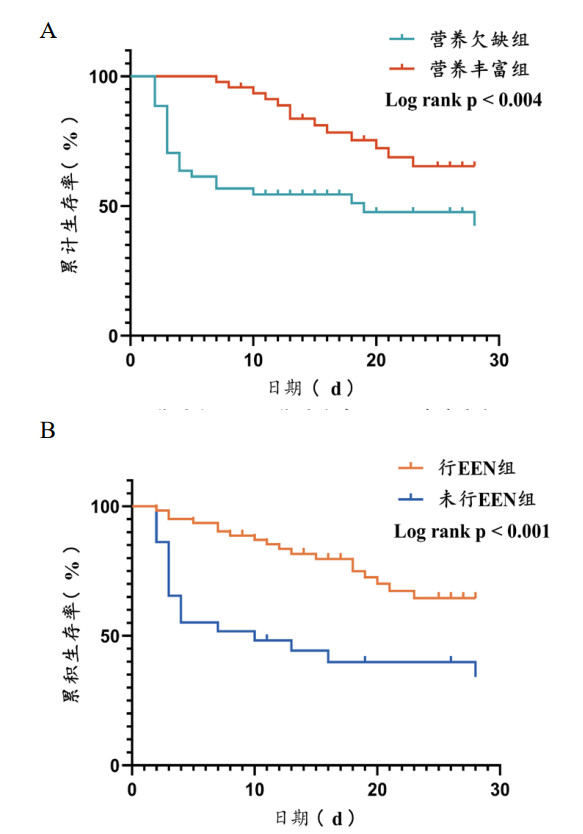

以能量摄入量为16.94 kcal/(kg·d)作为截断值进行分组,能量欠缺组共计44例患者,能量充足组共计47例,能量欠缺组和能量丰富组比较,两组基线资料差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 1。能量欠缺组的ECMO转机时间(d)、住院时间(d)明显小于能量丰富组(P < 0.05),能量欠缺组的EN总占比也明显小于能量丰富组[49.74(0.00, 73.81)% vs. 80.77(56.71, 85.56)%, P < 0.001]。能量丰富组的存活率明显高于能量欠缺组[66.0%(31/47) vs. 43.2%(19/44), P=0.029],这与使用Kaplan-Meier生存分析比较两组患者的28 d生存率的结果相同,见图 4A,能量欠缺组的28 d死亡风险是能量丰富组的2.595倍(P=0.004)。

| 指标 | 能量欠缺组(n=44) | 能量丰富组(n=47) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 男性(n, %) | 29 (65.9) | 35 (74.5) | 0.798 | 0.372 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 47.89±14.15 | 52.02±16.32 | -1.287 | 0.201 |

| BMI b | 24.34 (22.04, 26.42) | 24.49 (22.98, 25.95) | -0.524 | 0.600 |

| 原发疾病(n, %) | 8.843 | 0.547 | ||

| 急性心肌梗死 | 18 (40.9) | 16 (34.0) | ||

| 暴发性心肌炎 | 11 (25.0) | 6 (12.8) | ||

| 呼吸衰竭 | 2 (4.5) | 7 (14.9) | ||

| 脓毒性休克 | 3 (6.8) | 5 (10.6) | ||

| 中毒 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.1) | ||

| 其他 | 9 (20.5) | 12 (25.5) | ||

| ECMO模式(n, %) | 5.073 | 0.079 | ||

| VV | 3 (6.8) | 10 (21.3) | ||

| VA | 16 (36.4) | 19 (40.4) | ||

| ECPR | 25 (56.8) | 18 (38.3) | ||

| 转机时间(d)b | 4.2 (2.6, 7.0) | 7.0 (5.3, 11.1) | -3.923 | < 0.001 |

| 住院时间(d)b | 12.0 (3.0, 26.0) | 20.0 (12.0, 32.0) | -3.231 | 0.001 |

| 存活(n, %) | 19 (38.0) | 31 (66.0) | 4.762 | 0.029 |

| EN总占比(%)b | 49.7 (0.0, 73.8) | 80.8 (56.7, 85.6) | -4.068 | < 0.001 |

| 糖摄入占比(%)a | 51.5±12.5 | 50.3±8.7 | 74.338 | 0.591 |

| 脂质摄入占比(%)b | 22.4 (9.4, 29.7) | 30.3 (28.1, 32.9) | -3.714 | < 0.001 |

| 蛋白摄入占比(%)b | 23.1 (18.9, 37.1) | 19.6 (17.5, 22.2) | -3.457 | < 0.001 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

|

| A:能量欠缺组及能量充分组28 d生存分析;B:EEN组与非EEN组28 d生存分析 图 4 患者28 d生存分析 Fig 4 28-day survival analysis |

|

|

EEN组共计62例患者,非EEN组共计29例EEN组与非EEN组比较,两组基线资料差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 2。EEN组的转机时间(d)、住院时间(d)、每日每标准公斤体重能量摄入量[kcal/(kg·d)]、EN总占比(%)、脂质摄入占比(%)、蛋白摄入占比(%)的差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),其中EEN组的能量摄入量及EN总占比明显高于非EEN组[能量摄入量:17.120±5.517 kcal/(kg·d)比13.370±7.268 kcal/(kg·d), P=0.008;EN总占比:78.6(62.9, 85.0)% vs. 0.0(0.0, 30.3)%, P < 0.001]。EEN组的存活率也明显高于非EEN组的存活率[66.1%(41/62)比31.0%(9/29), P=0.002],与采用Kaplan-Meier生存分析比较两组患者的28 d生存率的结果相同,见图 4B,非EEN组的28 d死亡风险是EEN组的2.981倍(P < 0.001)。

| 指标 | EEN组(n=62) | 非EEN组(n=29) | 统计值 | P值 |

| 男性(n,%) | 43 (69.4) | 21 (72.4) | 0.089 | 0.766 |

| 年龄(岁)a | 50.55±15.55 | 48.90±15.17 | 0.476 | 0.635 |

| BMI a | 24.45±3.02 | 24.89±3.86 | -0.583 | 0.561 |

| 原发疾病(n, %) | 17.053 | 0.073 | ||

| 急性心肌梗死 | 24 (38.7) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| 暴发性心肌炎 | 16 (25.8) | 1 (3.4) | ||

| 呼吸衰竭 | 7 (11.3) | 2 (6.9) | ||

| 脓毒性休克 | 4 (6.5) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| 中毒 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.4) | ||

| 其他 | 10 (16.1) | 11 (37.9) | ||

| ECMO模式(n, %) | 2.237 | 0.327 | ||

| VV | 10 (16.1) | 3 (10.3) | ||

| VA | 26 (41.9) | 9 (31.0) | ||

| ECPR | 26 (41.9) | 17 (58.6) | ||

| 转机时间(d) b | 6.6 (4.8, 10.2) | 3.9 (2.2, 7.3) | -2.730 | 0.006 |

| 住院时间(d) b | 19.0 (12.0, 28.3) | 8.5 (3.0, 27.5) | -2.932 | 0.003 |

| 存活(n, %) | 41 (66.1) | 9 (31.0) | 9.830 | 0.002 |

| 每日每标准公斤体重能量摄入量[kcal/ (kg·d)] a | 17.120±5.517 | 13.370±7.268 | 2.723 | 0.008 |

| 每日每标准公斤体重蛋白摄入量[g/ (kg·d)]b | 0.825 (0.683, 1.083) | 0.840 (0.740, 1.030) | -0.204 | 0.838 |

| EN总占比(%)b | 78.6 (62.9, 85.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 30.3) | -6.709 | < 0.001 |

| 糖摄入占比(%)b | 50.1 (47.3, 55.4) | 47.6 (37.1, 62.7) | -0.924 | 0.356 |

| 脂质摄入占比(%)b | 29.3 (25.3, 31.8) | 15.3 (0.0, 32.4) | -2.956 | 0.003 |

| 蛋白摄入占比(%)b | 19.7 (17.6, 22.4) | 28.8 (21.4, 43.1) | -4.088 | < 0.001 |

| 注:a为(x±s),b为M(Q1, Q3) | ||||

近年来,ECMO越来越多地被应用于治疗心肺功能不全的患者中,而在绝大多数接受ECMO治疗的患者中都存在着明显能量摄入不足的情况[12]。本研究中,91例患者的平均能量摄入量为(15.92±6.34) kcal/(kg·d),这与指南所推荐的25~30 kcal/(kg·d)的能量摄入目标相差甚远,而达到25 kcal/(kg·d)最低能量摄入要求的仅占6.60%(6/91)。笔者考虑可能与以下因素有关。首先,ECMO患者通常多使用气管插管、机械通气,伴随心功能不全也需要限制液体入量,导致患者无论是EN或是PN摄入量均减少[10];其次,ECMO患者常常表现为高代谢状态,因其多为急性发病或继发炎症等导致蛋白质分解代谢增高及胰岛素抵抗[13-14],并且随着时间进展患者长期处于低级别持续性炎症状态[15],对于能量需求量大,常规给予的能量相对不充足;再者,ECMO患者因血流动力学受损而至内脏充血,长期使用血管活性药物、类固醇激素及镇静药物,导致患者胃肠道功能受到损害,大量营养素吸收减少[6, 10]。因此,ECMO患者常常因能量摄入不足导致营养不良。本研究中,Kaplan-Meier生存分析展示了能量欠缺组的28 d生存率明显低于能量丰富组,能量欠缺组的28 d死亡风险是能量丰富组的2.595倍(P=0.004)。然而也有研究表示非蛋白卡路里摄入未达目标值对重症患者的临床预后并没有影响[16],这仍需大量的实验去证实二者之间的相关性。

然而,并不是能量摄入越多对患者的预后越好。有关研究报道,重症患者摄入的卡路里/静息能量消耗达到70%时最具有生存优势[17],同时也有研究表明,能量摄入目标维持在80%的体外生命支持(ECLS)患者病死率较低[18]。患者允许性喂养不足是对能量摄入量的一种限制,据观察,限制热量摄入对降低患者感染率及提高生存率有显著有意义[17, 19]。本研究的数据显示当能量摄入超过24.33 kcal/(kg·d)时,患者的死亡风险有逐步提高的趋势。既往一些研究提示过度喂养的风险很高,主要是因为非营养性的能量摄入未被计算在内,包括与药物配伍的葡萄糖溶液以及镇痛镇静用的异丙酚等含有脂质成分的药物[20-21]。本研究在能量摄入的计算中已将与药物配伍所使用的葡萄糖计算在内,因此本研究所得出最适能量摄入的高值(折算为能量摄入达标率是(97.32%)较其他研究数值高,这也是本研究较其他研究更为科学之处。

目前已用有大量研究表明EEN对于ECMO患者有良好的预后[22-23],但是也有研究表明EEN对患者预后并没有影响[9]。本研究中EEN组的存活率(66.1%)明显高于非EEN组的存活率(31.0%)(P=0.002),同时Kaplan-Meier生存分析也提示非EEN组的28 d死亡风险是EEN组的2.981倍(P < 0.001),结论提示了EEN对ECMO患者的预后情况是有益的。对于ECMO患者,EN有较多的优势,一方面EN可以维持肠道的完整性,有助于促进分泌型免疫球蛋白A产生免疫细胞、B细胞和浆细胞[24],这些都与细菌侵袭、系统性感染以及多脏器功能衰竭的风险有关[25-26]。另一方面,也有相关研究表示EN并不会加重小肠的缺血,即使是小剂量的营养也有助于保护肠道上皮功能,改善临床预后[27-28]。同时,EN也可避免使用PN带来的一系列并发症,主要包括中心静脉导管感染率的增加、真菌感染风险增大以及液体摄入过量等[29-30]。尽管EN有着众多的好处,部分临床医生仍不考虑早期使用EN,主要是因为EN肠道血流量的增多而增加心脏负担、肠蠕动弱不利于EN营养液吸收、EN相关并发症等[31-32]。然而,为何在ECMO早期(< 48 h)行EN会影响患者的总体预后这一点尚不明确。一方面可能是因为EN更符合机体的生理过程,有助于肠道功能的早期恢复,从而带动机体多脏器功能的恢复,并且早期避免感染的可能;另一方面EEN也有助于患者能量的摄入,进而使机体获得更多的营养支持来修复机体的损伤、抵抗外来微生物的入侵,进而提高患者的生存率。本研究中EEN组的患者早期能量摄入量显著大于非EEN组(P=0.008),并且能量主要是由EN途径提供(P < 0.001),能量丰富组的EN摄入量也显著高于能量欠缺组(P < 0.001),提示ECMO患者主要能量摄入来自EN途径,符合上述猜想。

本研究仍然存在许多不足之处。首先,在能量摄入的数据采集过程中,本研究虽然计算了药物配伍所使用的葡萄糖摄入量,但忽视了镇静药物中所含脂质的能量供应;同时,在EN摄入部分,少数清醒患者(5/91例)在ECMO早期维持期间已可以经口或鼻胃/肠管少量摄入食物,研究未计算这一部分的能量摄入。其次,本实验中EEN组包含了后期停止或中断EN的患者,主要原因是发生EN相关并发症,本研究也未将EN并发症对患者的预后影响考虑在内。最后,每日每标准公斤能量摄入较高提示患者的总体预后较差的可能,本研究中因这一部分样本量较小,故未将此部分单独分组进行分析,这是本研究的一大遗憾,后续研究望增加样本量进一步完善研究结果。

综上所述,能量摄入不足普遍存在于ECMO患者,ECMO患者的能量摄入在16.94 kcal/(kg·d)以上时对预后是保护性因素,EEN有助于提高ECMO患者早期能量摄入量并改善预后。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 丁涛、李伟和陈旭锋查阅了文献,构思了这项研究;时育彤、李天时、李谢伦、徐微笑、周鹏和安迪参与了获得伦理批准、收集整理和统计分析临床数据;李伟和陈旭锋确认所有原始数据的真实性;丁涛写了文章的初稿,李伟、朱轶和张忠满参与审阅和修改稿件;所有作者都已阅读并批准了手稿的最终版本

| [1] | Yun JH, Hong SB, Jung SH, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of bloodstream infection in patients under extracorporeal membranous oxygenation[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2021, 36(9): 1053-1060. DOI:10.1177/0885066620985538 |

| [2] | 中国急诊危重症患者肠内营养治疗专家共识组. 中国急诊危重症患者肠内营养治疗专家共识[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2022, 31(3): 281-290. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2022.03.004 |

| [3] | Mart MF, Girard TD, Thompson JL, et al. Nutritional Risk at intensive care unit admission and outcomes in survivors of critical illness[J]. Clin Nutr, 2021, 40(6): 3868-3874. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2021.05.005 |

| [4] | Mogensen KM, Robinson MK, Casey JD, et al. Nutritional status and mortality in the critically ill[J]. Crit Care Med, 2015, 43(12): 2605-2615. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001306 |

| [5] | Pardo E, Lescot T, Preiser JC, et al. Association between early nutrition support and 28-day mortality in critically ill patients: the FRANS prospective nutrition cohort study[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 7. DOI:10.1186/s13054-022-04298-1 |

| [6] | Dresen E, Naidoo O, Hill A, et al. Medical nutrition therapy in patients receiving ECMO: evidence-based guidance for clinical practice[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2023, 47(2): 220-235. DOI:10.1002/jpen.2467 |

| [7] | Davis RC 2nd, Durham LA 3rd, Kiraly L, et al. Safety, tolerability, and outcomes of enteral nutrition in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2021, 36(1): 98-104. DOI:10.1002/ncp.10591 |

| [8] | Kim S, Jeong SK, Hwang J, et al. Early enteral nutrition and factors related to in-hospital mortality in people on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Nutrition, 2021, 89: 111222. DOI:10.1016/j.nut.2021.111222 |

| [9] | Brisard L, Bailly A, Le Thuaut A, et al. Impact of early nutrition route in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a retrospective cohort study[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2022, 46(3): 526-537. DOI:10.1002/jpen.2209 |

| [10] | D'Alesio M, Martucci G, Arcadipane A, et al. Nutrition during extracorporeal life support: a review of pathophysiological bases and application of guidelines[J]. Artif Organs, 2022, 46(7): 1240-1248. DOI:10.1111/aor.14215 |

| [11] | Chen H, Sun Q, Chao YL, et al. Lung morphology impacts the association between ventilatory variables and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 59. DOI:10.1186/s13054-023-04350-8 |

| [12] | Hunt MF, Pierre AS, Zhou X, et al. Nutritional support in postcardiotomy shock extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients: a prospective, observational study[J]. J Surg Res, 2019, 244: 257-264. DOI:10.1016/j.jss.2019.06.054 |

| [13] | Farías MM, Olivos C, Díaz R. Nutritional implications for the patient undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Nutr Hosp, 2015, 31(6): 2346-2351. DOI:10.3305/nh.2015.31.6.8661 |

| [14] | MacGowan L, Smith E, Elliott-Hammond C, et al. Adequacy of nutrition support during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Clin Nutr, 2019, 38(1): 324-331. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.01.012 |

| [15] | Moore FA, Phillips SM, McClain CJ, et al. Nutrition support for persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2017, 32(1_suppl): 121S-127S. DOI:10.1177/0884533616687502 |

| [16] | Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, et al. Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in critically ill adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(25): 2398-2408. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1502826 |

| [17] | Zusman O, Theilla M, Cohen J, et al. Resting energy expenditure, calorie and protein consumption in critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Crit Care, 2016, 20(1): 367. DOI:10.1186/s13054-016-1538-4 |

| [18] | Lu MC, Yang MD, Li PC, et al. Effects of nutritional intervention on the survival of patients with cardiopulmonary failure undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy[J]. In Vivo, 2018, 32(4): 829-834. DOI:10.21873/invivo.11315 |

| [19] | Doig GS, Simpson F, Heighes PT, et al. Restricted versus continued standard caloric intake during the management of refeeding syndrome in critically ill adults: a randomised, parallel-group, multicentre, single-blind controlled trial[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2015, 3(12): 943-952. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00418-X |

| [20] | Terblanche E, Remmington C. Observational study evaluating the nutritional impact of changing from 1% to 2% propofol in a cardiothoracic adult critical care unit[J]. J Hum Nutr Diet, 2021, 34(2): 413-419. DOI:10.1111/jhn.12835 |

| [21] | Dickerson RN, Buckley CT. Impact of propofol sedation upon caloric overfeeding and protein inadequacy in critically ill patients receiving nutrition support[J]. Pharmacy, 2021, 9(3): 121. DOI:10.3390/pharmacy9030121 |

| [22] | Umezawa Makikado LD, Flordelís Lasierra JL, Pérez-Vela JL, et al. Early enteral nutrition in adults receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an observational case series[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2013, 37(2): 281-284. DOI:10.1177/0148607112451464 |

| [23] | Ohbe H, Jo T, Yamana H, et al. Early enteral nutrition for cardiogenic or obstructive shock requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a nationwide inpatient database study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(8): 1258-1265. DOI:10.1007/s00134-018-5319-1 |

| [24] | Kang W, Kudsk KA. Is there evidence that the gut contributes to mucosal immunity in humans?[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2007, 31(3): 246-258. DOI:10.1177/0148607107031003246 |

| [25] | Jabbar A, Chang WK, Dryden GW, et al. Gutimmunology and the differential response to feeding andstarvation[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2003, 18(6): 461-482. DOI:10.1177/0115426503018006461 |

| [26] | Kudsk KA. Current aspects of mucosal immunology and its influence by nutrition[J]. Am J Surg, 2002, 183(4): 390-398. DOI:10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00821-8 |

| [27] | Shukla A, Chapman M, Patel JJ. Enteral nutrition in circulatory shock: friend or foe?[J]. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2021, 24(2): 159-164. DOI:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000731 |

| [28] | Patel JJ, Kozeniecki M, Peppard WJ, et al. Phase 3 pilot randomized controlled trial comparing early trophic enteral nutrition with "No enteral nutrition" in mechanically ventilated patients with septic shock[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2020, 44(5): 866-873. DOI:10.1002/jpen.1706 |

| [29] | Lappas BM, Patel D, Kumpf V, et al. Parenteral nutrition: indications, access, and complications[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2018, 47(1): 39-59. DOI:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.10.001 |

| [30] | Stratman RC, Martin CA, Rapp RP, et al. Candidemia incidence in recipients of parenteral nutrition[J]. Nut Clin Prac, 2010, 25(3): 282-289. DOI:10.1177/0884533610368704 |

| [31] | Park J, Heo E, Song IA, et al. Nutritional support and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients supported with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Clin Nutr, 2020, 39(8): 2617-2623. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2019.11.036 |

| [32] | Ohbe H, Jo T, Matsui H, et al. Early enteral nutrition in patients undergoing sustained neuromuscular blockade: a propensity-matched analysis using a nationwide inpatient database[J]. Crit Care Med, 2019, 47(8): 1072-1080. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003812 |

2024, Vol. 33

2024, Vol. 33